|

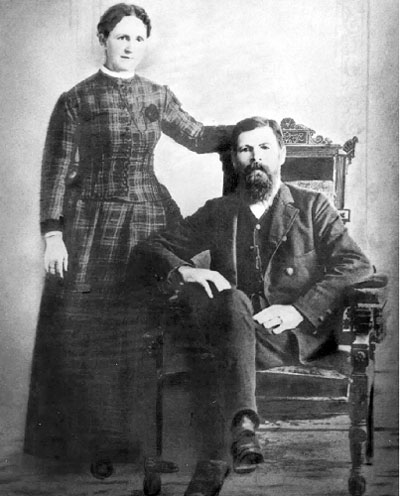

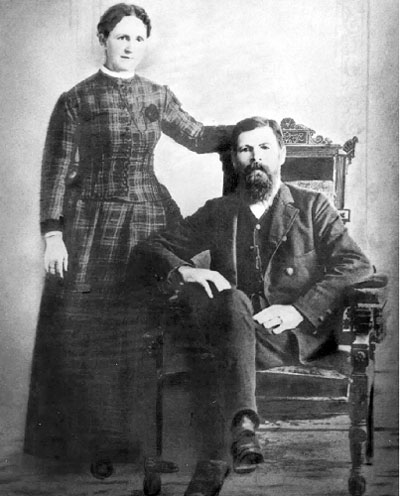

| Charlotte and Timothy Munger were married at the end of the war. Photo courtesy Mark Dias. |

It's easy to overlook California's Civil War legacy in a war that was fought a half-continent or more away. But at least fifty-one Union veterans are buried in a Central California town, Arroyo Grande, in San Luis Obispo County. This excerpt from the forthcoming book Patriot Graves: Discovering a California Town's Civil War Heritage, is part of an examination of what those veterans accomplished as young men on the battlefield and what they contributed, as mature men, in building a community on the California coast.

When Timothy Munger died in Arroyo Grande in 1911, he was a well-liked man whose funeral, according to a San Luis Obispo newspaper account, was heavily attended and observed with full military honors. Munger was 73, a former justice of the peace, and had just been elected city clerk when his health began to decline.[1] It was a quiet end to a life that, by odds, should have been even shorter, because Munger had survived the Confederate prisoner of war system-in his case, Libby Prison in Virginia, a former tobacco warehouse.

|

| Charlotte and Timothy Munger were married at the end of the war. Photo courtesy Mark Dias. |

So had Erastus Fouch, the 75th Ohio Volunteer Infantry veteran who was such a booster for founding a local high school. Fouch had the good luck to be exchanged fifty-one days after his capture at Gettysburg. At least five of his Company I comrades weren't so lucky: they died as Confederate prisoners of war.[2]

If there was luck in being captured, it was only in the timing. Munger was captured at the end of Gen. Philip Sheridan's campaign against Confederate Gen. Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley; the 8th Ohio was surprised by Early's troops in January 1865 and 500 of them were taken prisoner. Munger and his comrades wouldn't have felt lucky-they were, according to one source, "marched through snow, barefooted, and with scarcely any food, to Staunton, where they were loaded on stock cars and sent to Libby Prison. The sufferings of the men were dreadful at the hands of a cruel and relentless foe."[3] Their suffering did not last long: they were paroled in February. By then, according the journal of a less-fortunate Union officer imprisoned at Libby, the menu consisted of bread, turnips, rice, and, very rarely, meat-a diet so meager that a visiting Catholic priest, a Southerner, complained to the Libby commandant.[4] Records are incomplete, but an estimated 30,000 Union prisoners died in Confederate custody during the Civil War-the most notorious camp, Georgia's Andersonville, accounted for 13,000 deaths-but ironically, part of the blame for the subsistence rations at Libby and elsewhere lay in the battlefield success of Union generals like Philip Sheridan. Sheridan was pursuing, like Sherman, a policy of total war, including the destruction of crops, and Timothy Munger had been captured in one of the most important food-producing regions in the Confederacy.

The Shenandoah Valley was a constant torment to Lincoln and the Union. Not only was it supplying food, including wheat, to southern armies, but it was a natural invasion route-analogous to the Ho Chi Minh trail, used by North Vietnam to feed troops and supplies into the Mekong Delta during America's war in Vietnam. Early in the war, Stonewall Jackson's troops had played hide-and-seek in the Valley-killing, in the process, Erastus Fouch's brother, Leonidas, in a heated little battle at McDowell--tying down 60,000 Union troops. The Blue Ridge Mountains on the valley's eastern flank effectively shielded Lee's army from sight during his invasions of Maryland in 1862 and Pennsylvania in 1863. In 1864, Confederate Gen. Jubal Early had threatened Washington D.C. with invasion, an event that featured a future Supreme Court justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., then a young Union officer, bellowing "Get down, you damn fool!" at a civilian in a stovepipe hat watching the combat, completely enraptured. The civilian was President Lincoln.

|

|

So, in August 1864, the Union Army's commander in the field, Ulysses Grant, dispatched a small, aggressive, and brilliant general, Philip Sheridan, to the Shenandoah Valley to deal with Jubal Early, and to deprive the Confederacy of the food the Valley provided, once and for all. At least six Arroyo Grande settlers, including Timothy Munger, served under Sheridan in the Valley, but they and Sheridan had more than a match in Early, arguably one of the South's most able generals. And Early had inherited elite troops: among the men under his command were those who had fought with Stonewall Jackson in the Valley campaign of 1862 and in two decisive victories Jackson had delivered-at Second Bull Run in 1862 and in the brilliant flanking maneuver at Chancellorsville in 1863.

Early-even in losses like Gettysburg-had a reputation for hitting Union troops hard, and he had been decidedly Jacksonian in consistently outwitting and outfighting Union forces earlier in 1864, once Lee had dispatched him to the Shenandoah Valley. Early must have seemed a reincarnation of Stonewall Jackson: not only did he threaten Washington, but on July 30, he ordered his cavalry to burn Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, during a raid; 200 homes and buildings were destroyed; one of them contained a black resident whom the Confederates had murdered by trapping him inside. Early was so successful in raiding, fighting, and disappearing that he went through two Union generals-Franz Sigel and David Hunter-before Sheridan was summoned by Grant to take command.

Lincoln had pressured Grant, now bogged down in the Virginia trenches in front of Petersburg, for a change in command because the election was approaching and Early was as much a political as a military threat; his victories were sapping civilian morale and that meant Lincoln was losing potential votes.

But, given how roughly Early had handled two earlier commanders, Grant's orders carried an explicit footnote for Sheridan: Don't lose. And Sheridan, who took over August 7, overestimated the size of Early's forces when he, in fact, had 50,000 men to Early's 14,000. Meanwhile, Early's commander, Lee, underestimated the size of Sheridan's army, failing to convince his junior commander that it was as small as the Confederate commander insisted it was. The result was three weeks of the two armies sparring at a distance and an evolution in Early's opinion of the other side: they might outnumber him, but their commander, Sheridan, was timid.

Early, of course, was wrong, but, ironically, the signal for Sheridan's first offensive in the Valley came far to the south, when Sherman took Atlanta early in September. This was enough of a turning point-it lifted the cloud that was hanging over Lincoln's chances for re-election-so that Grant ordered Sheridan to go into the valley, to destroy Early, and to leave the Shenandoah "a barren waste."[6] The gloves were off.

It was Timothy Munger and Sheridan's cavalry who would be behind the force of the first blow Sheridan landed, on September 19, 1864. Early's army was separated, and a division under Confederate general Stephen Ramseur was isolated near Winchester, along Opequon Creek. When Sheridan fell on them, he was late-his infantry had to advance through a narrow canyon that the cavalry had cleared of Confederates-but he hit hard, driving the Confederates back; then Sheridan himself was stopped as the rest of Early's command arrived to rescue Ramseur's division. What had been intended to be a lightning attack was now a slugging match that included Isaac Dennis Miller's 24th Iowa regiment; Miller would, after the war, farm in Morro Bay and Cayucos, come to Arroyo Grande to farm the Upper Valley and run a butcher shop on the side. This battle was a turning point in Miller's life; as the 24th Iowa Volunteer Infantry emerged from a woods, they were flanked by a hidden Confederate unit that opened fire with devastating results. Among those cut down was Miller, with three bullet wounds to his right leg and a piece of shrapnel in his ankle; evacuated to a field hospital, Miller refused amputation; the leg was saved, but he would have difficulty walking the rest of his life.[7] Meanwhile, the Union assault had been stopped cold.

Sheridan improvised. He sent two divisions of cavalry, including Munger's 8th Ohio, to the far left of the Confederate line along with two divisions of George Crook's VIII Corps, which included two men who would settle in Arroyo Grande-Samuel McBane, 123rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and George Purdy, 11th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry. The cavalry and infantry were moving out together when Sheridan appeared and rode among them, shouting at them to "kill every son of a bitch!" [8] The infantry hit Early's lines while the cavalry looped around to the extreme left-somewhere in between, Confederate Col. George Patton, the grandfather of the World War II tank commander, was killed-and Early's men collapsed. The use of massed cavalry had been especially telling, and Sheridan was using units like the 8th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in a way that would presage the panzer tactics of Heinz Guderian and the tank tactics of George Patton in the Second World War; at this point in the war, superior Union mounts and better-trained troopers would prove decisive in the Valley. But Early, defeated at what would be called the Third Battle of Winchester, wasn't finished yet.

Neither was Sheridan. After Winchester, he turned to the second of Grant's goals, to deprive Early and Lee of the Shenandoah's food and forage: for the next two weeks, a campaign was waged on crops in the field. Valley farmers called it "The Burning;" on a smaller scale, it was the same kind of war, on civilian property, that Sherman would soon wage far to the south in Georgia. Like Sherman's "little devils," Sheridan's men went to work enthusiastically.

"I shall never forget that day," on Valley woman wrote of the arrival of Sheridan's men. "It looked to me like the day of judgement [sic], our Father's old mill & barn and [cloth] mill and all the Mills and barns ten miles up the creek were burning at once and the flames seemed to reach the skies it was awful to watch."[9]

One elderly farmer was spared; when Sheridan's men arrived at his farm, he was waiting for them-with a hearty dinner, which he and his wife cheerfully offered them. They ate the way hungry young men will and afterward, they hesitated as to what to do next. Their lieutenant eyed the farmer's barn and reminded his men that they were not obligated to burn an empty barn. Both the officer and his detail agreed that the barn looked empty to them. They rode away and left it untouched. Two thousand other barns, Sheridan estimated, were burned to the ground.[10]

The Burning had a practical short-term military effect: running short on food for his Army of the Valley, Early's hand was forced: he would have to attack Sheridan while his army was still capable of it.

Footnotes:

1 San Luis Obispo Breeze, October 7, 1911, p. 1.

2 Roster of the 75th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, http://www.civilwarindex.com/armyoh/rosters/75th_oh_infantry_roster.pdf

3 “8th Ohio Cavalry,” http://www.ohiocivilwar.com/cwc8.html

4 Bartleson, Frederick A., Letters from Libby Prison,

5 “Civil War Defenses of Washington,” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/cwdw/learn/historyculture/president-lincoln- under-direct- fire-at- fort-stevens.htm

6 Lt. Col. Joseph W.A. Whitehorne, “The Battle of Cedar Creek: A Self-Guided Tour,” Center of Military History, United States Army, April 1991.

7 Troy B. Goss, “Pvt. Isaac Dennis Miller,” Troy’s Genealogue, http://genealogue.net/millcivwar.html

10 Ibid.

About the Author

Jim Gregory taught history at Mission College Preparatory High School in San Luis Obispo and at Arroyo Grande High School for thirty years, retiring in 2015. Raised in the Arroyo Grande Valley, Gregory' s first book. World War in Arroyo Grande, was published in January by The History Press. Patriot Graves: Discovering a California Town's Civil War Heritage, is nearing completion. In both books, Gregory seeks to connect the people of his home town with the American history that he loved to teach; a future project will address the area during the 1920s and 1930s.