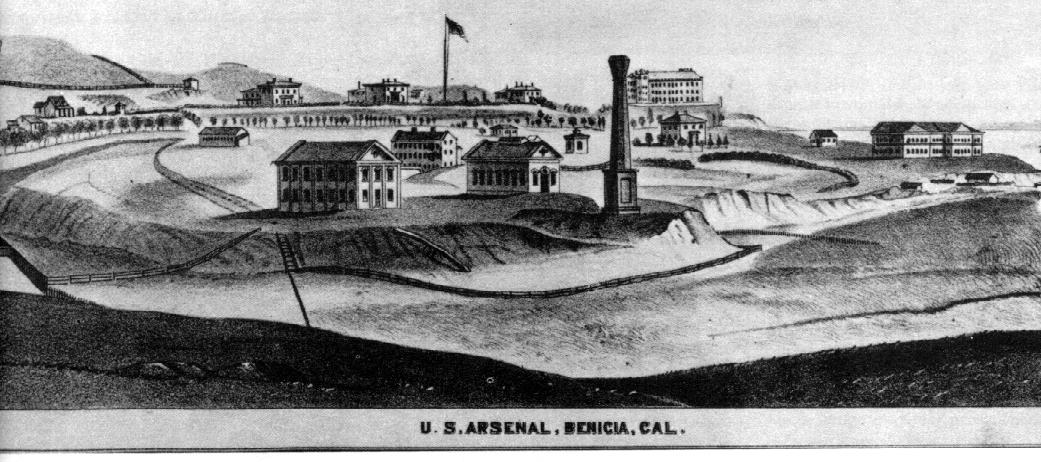

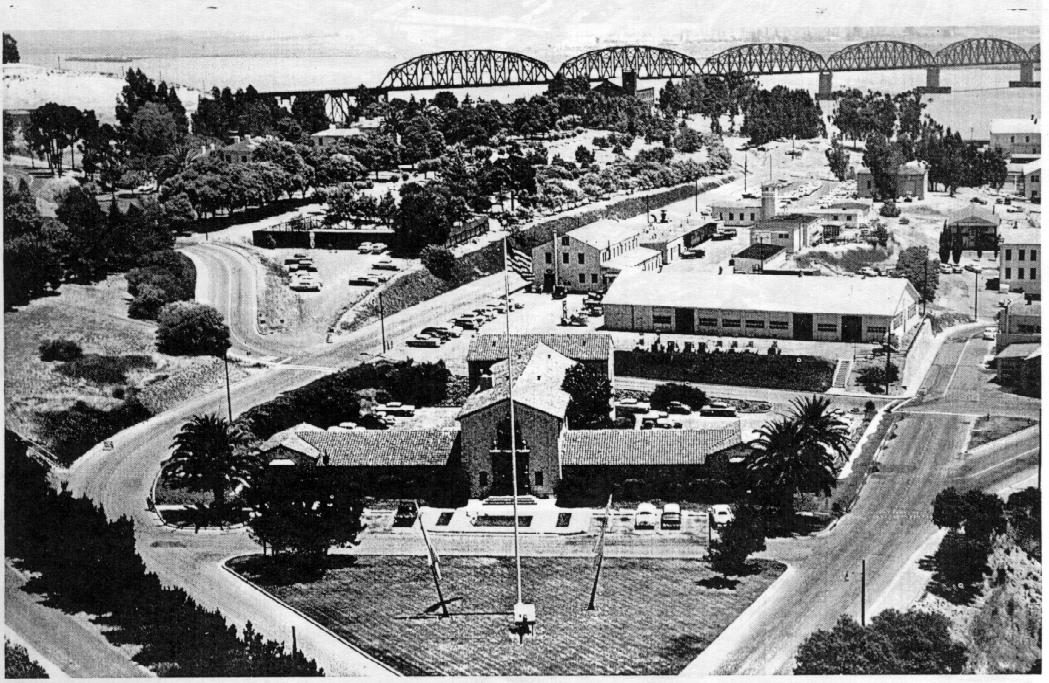

That the United States should have acquired a military reserve adjoining the City of Benicia was a direct result of the town's establishment and of the near-obsession of Semple to promote it. In this regard, Semple brought into the planned development Thomas O. Larkin of Monterey, former American Consul there and notable early-day diplomat, merchant and developer of Monterey and San Francisco. To support Semple, Larkin directed attention of the government and settlers to the new community. He urged both U.S. Navy and Army chiefs to establish installations adjacent to the new town, even to the extent of traveling to Washington to personally present his proposal to the Secretary of War. He was successful and the Government did acquire a tract of land containing 300 acres adjoining Benicia city limits on the east for a military reserve.