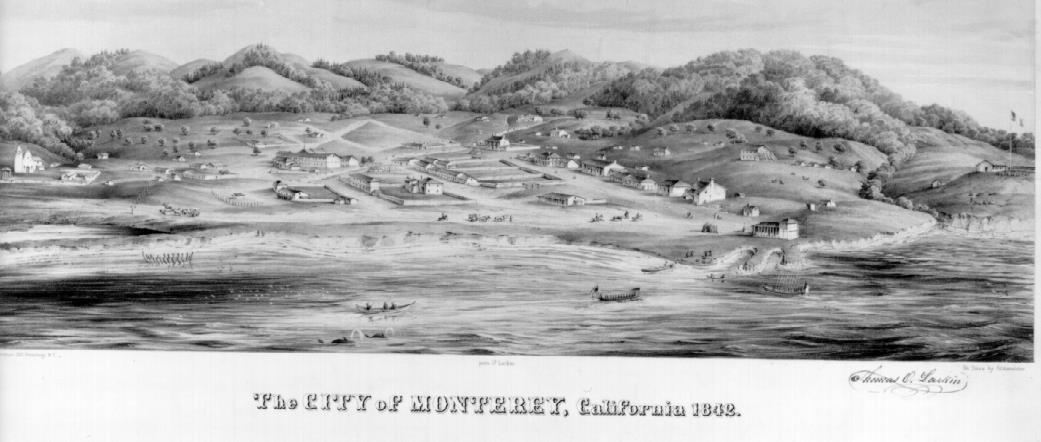

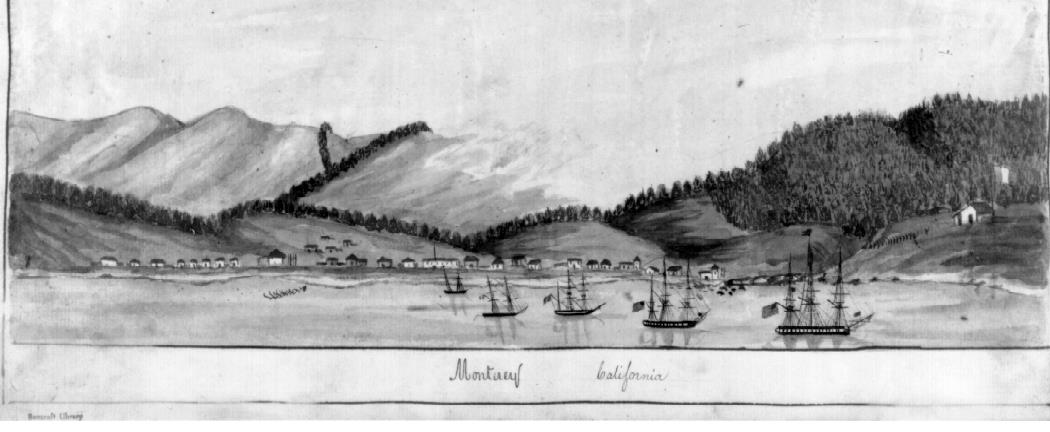

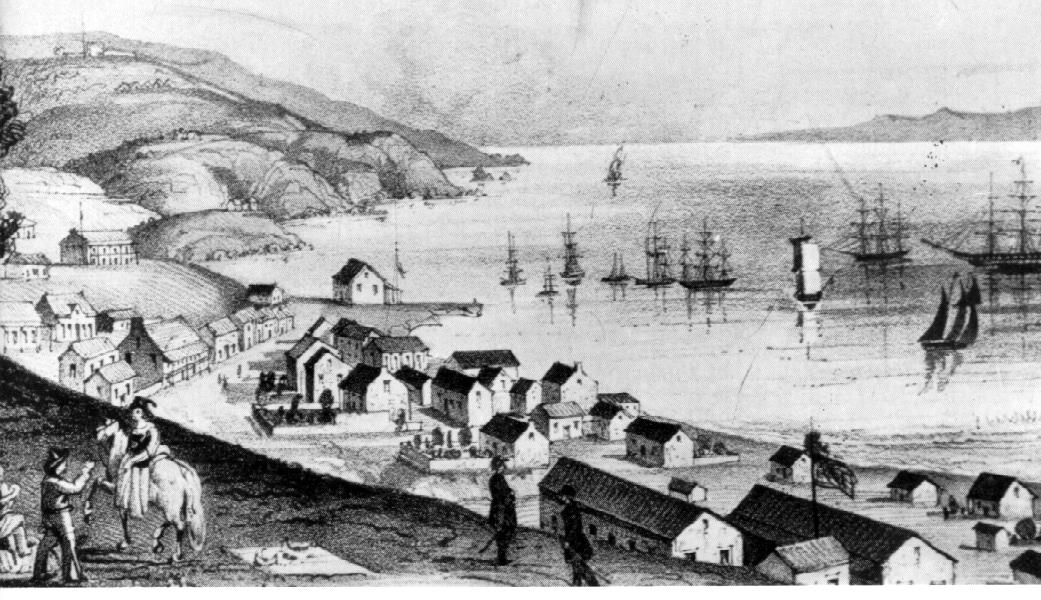

The Evolution of the Castillo at Monterey. From Gunpowder and Canvas , pg. 4-17 by the Author.

The Castillo at Monterey was the first to be started. Its evolution is described by some of the same sources that commented on the Castillo at San Francisco. H. H. Bancroft in The History of California, Vol. I, pg. 682 makes the following comments about the first development of this Castillo:

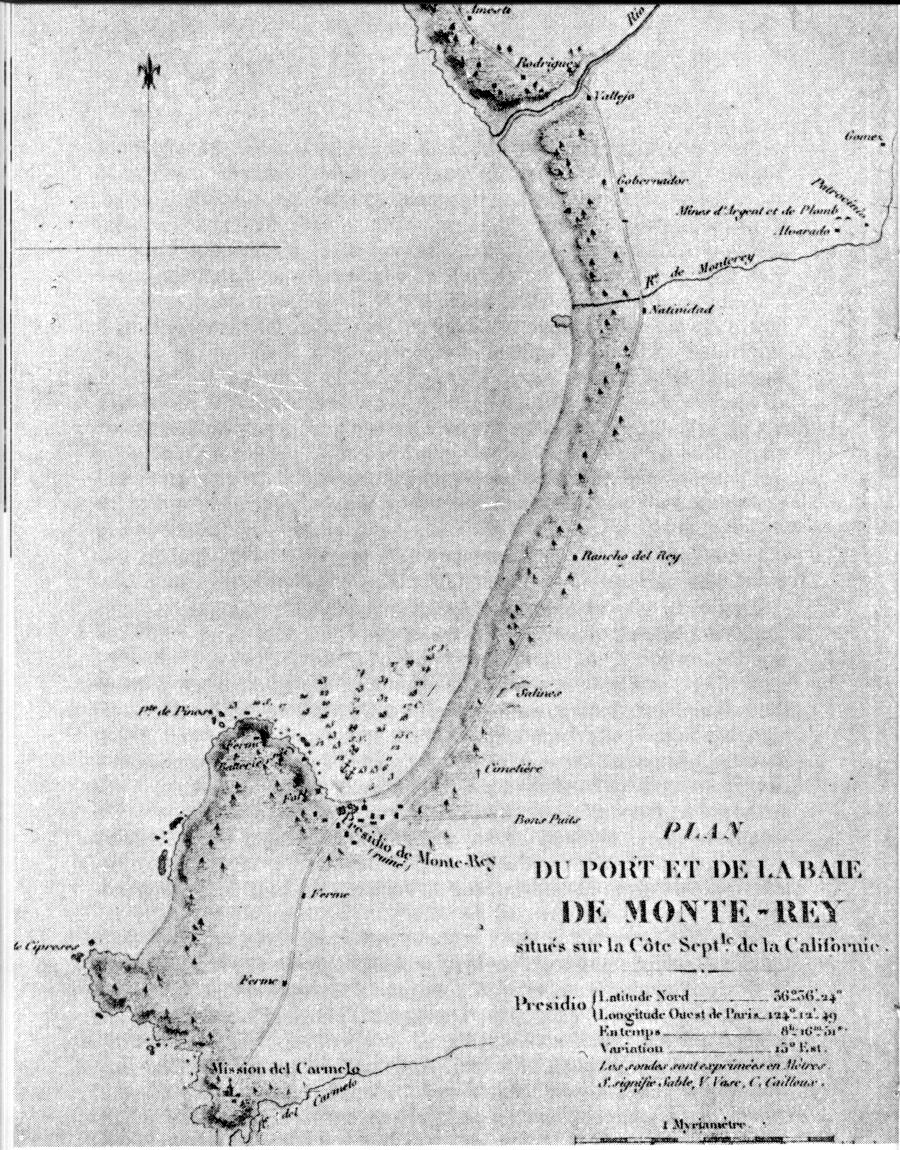

"The armament of Monterey at the time of Vancouver's first visit consisted of seven small guns planted outside the presidio walls without breastwork or protection from the weather. At the same time Bodega y Cuadra left some material, and men were sent at work on a battery to be erected on a neighboring eminence."

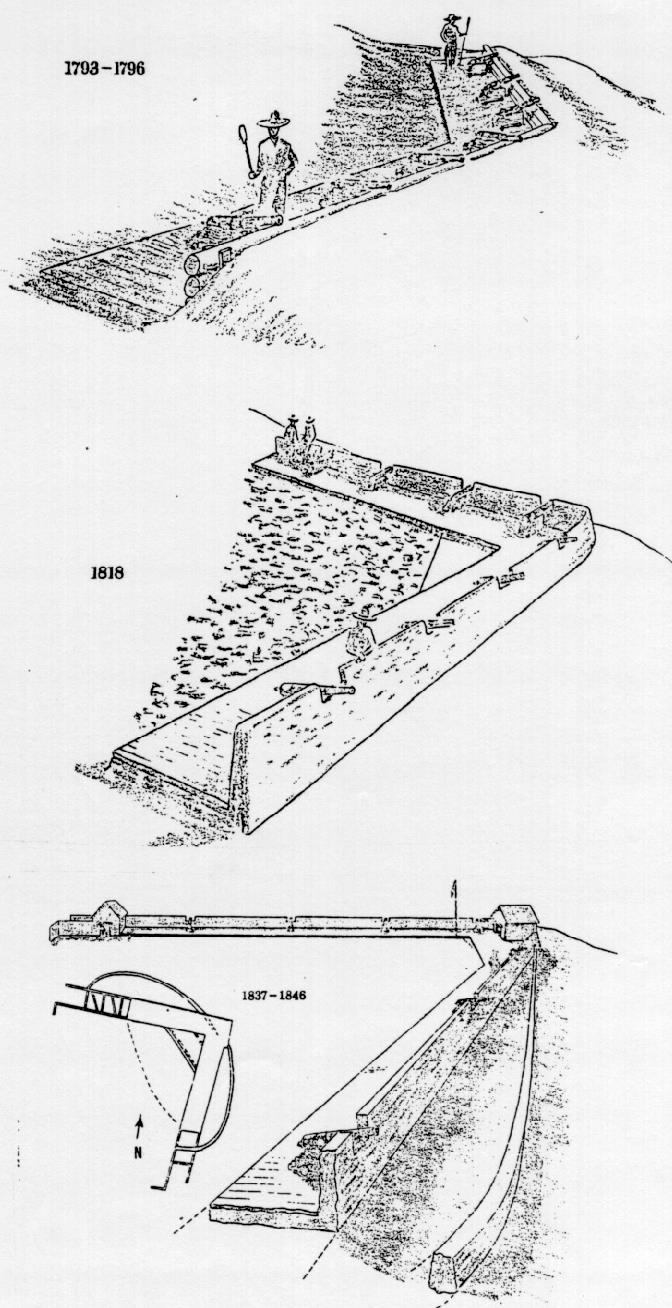

Accordingly on Vancouver's return in 1793 he found the guns mounted on a "sorry kind of barbet battery, consisting chiefly of a few logs of wood, irregularly placed; behind which those cannon, about eleven in number, are opposed to the anchorage, with very little protection in the front, and on their rear and flanks entirely open and exposed." This work cost $450, and while it might serve to prevent a foe from cutting out vessels at anchor, was entirely useless, as Cordoba reported in 1796, for the defense of the port. It does not appear that anything was done for its improvement before 1800. Additional comments made by Vancouver in 1793 from Vancouver in California 1792-1794 pg. 83 are as follows:

"The four dismounted cannon, together with those placed at the entrance into the Presidio, are intended for a fort to be built on a small Eminence that commands the anchorage. A large quantity of timber is at present in readiness for carrying that design into execution; which when completed, might certainly be capable of annoying vessels lying in that part of the bay which affords the greatest security, but could not be of any importance after a landing was accomplished, as the hills behind it might be easily gained, from whence the assailing party would soon oblige the fort to surrender; nor do I consider Monterey to be a very tenable port without an extensive line of works."

Further comments were made by Vancouver again in 1794 on page 241 of the above work as follows:

"At Monterey the cannon, which, on our former visit, were placed before the Presidio, were now removed to the hill, mentioned at that time as intended to be fortified for the purpose of commanding the anchorage. Here, is now erected a sorry kind of barbet battery, consisting chiefly of a few logs of woods, irregularly placed; behind which those cannon, about eleven in number, are opposed to the anchorage, with very little protection in the front, and on their rear and flanks open and exposed."

El Castillo's official life began sometime

in 1792 when initial plans for the fortifications were conceived.

Viceroy Revilla Gigido informed Governor Jose Arrillaga on February

16, 1793 that he had approved fortification plans for all four

of Alta California's presidios. Captain Vancouver refers to the

added armament during his visit stated above. His visit was clearly

the motivation for the next improvements. In 1796 Alberto de Cordoba

recommended changes to the Monterey fortifications for which a

drawing was submitted to the Viceroy. However, the drawing has

not been recovered to date. As a result of these plans, Cordoba

saw to the construction of a berm against the logs, the layout

of an esplanade, a powder magazine and a wooden barracks for the

artillerymen. Over the years other additions were made by the

Governor, which expanded the Castillo and made it more defensible.

A three-foot high adobe wall was added with merlons and embrasures.

Powder magazines were placed along the walls and the esplanade

was moved forward toward the edge of the hill. The basic structure

consisted of two 60-foot long wings arranged in a V-shape.

The Castillo of Monterey was not used in

anger until the 1818 period. As early as 1816, the inhabitants

of Alta California feared that South American revolutionaries

would view their lands as ripe for "liberation" and

Governor Pablo Vincente de Sola therefore took immediate steps

to renew and improve California's neglected defenses. Munitions

were particularly needed and in October 1816 a ship from San Blas

laden with "war stores" landed in Monterey. These stores

included eight 8-pounder cannon, 800 cannon balls, 100 English

muskets with bayonets, twenty cases of powder, 1000 flints, 20,000

one-ounce musket balls, and 20,000 cartridges. Two years passed

before Hippolyte Bouchard appeared off Monterey. On November 20,

1818 Bouchard's invasion force arrived in two ships; the Argentina,

carrying thirty-eight guns and two howitzers, and the Santa Rosa,

armed with twenty-six guns. Governor Sola's report of the battle

to the viceroy noted the surprisingly valiant role played by those

who manned the guns at the Castillo. Prior to the arrival of this

body, the Spanish had located a battery of three guns near the

shore. However, the Spanish were greatly outnumbered by the Bouchard

forces.

At dawn, November 21 the Santa Rosa opened

fire on the shore battery. The eight Spanish guns, six and eight

pounders were not all serviceable but returned fire and with much

skill and good luck were able to keep up a constant and effective

fire, which caused much damage to the frigate Santa Rosa. The

Bouchard forces lost five men, many more were wounded and transferred

to the Argentina before a cease-fire was requested and the Santa

Rosa lowered their flag.

Toward evening the Argentina moved out of

range of the Castillo's guns. Bouchard sent an officer under a

flag of truce to demand surrender of the province. Governor Sola

refused. The next morning Bouchard sent four hundred men ashore

in two groups to capture the Castillo and the Presidio. One group

proceeded directly to the Presidio, the other climbed the hillside

and stormed the Castillo from the rear, spiking the guns and burning

the barracks. The Spanish beat a careful retreat in the light

of such overwhelming forces. Bouchard captured Monterey and remained

in the capital for several days before setting fire to the Presidio

and then slipping away into the night to next terrorize Santa

Barbara.

In the ensuing years, the Castillo once

again sank into semi-ruin. In 1836 the Castillo was partially

rescued from the ignominy into which it was rapidly sinking by

the beginning of a more active phase in Alta California revolutionary

politics. In the years following Mexican independence, Californians

had endured a variety of laws and rules made, they believed, with

little or no consideration for the province's needs. Many Californians

came to hold strong feelings against central rule by Mexico. Although

most Californios did not favor absolute independence, they did

believe they should be consulted about decisions affecting their

activities.

At the end of 1835, Brevet Brigadier General

Jose Figueroa, one of the most respected of Mexico's Alta California

governors, had died and had named a Californian, Jose Castro as

his successor. However with pressure from Mexico, the civil and

military offices were united under Lieutenant Colonel Nicolas

Gutierrez, a Spaniard who had come from Mexico with Figueroa.

One day in 1836, the newly appointed General

Gutierrez decided to put an end to the Custom House officers'

open practice of accepting and keeping bribes. He did so by putting

a guard on board a vessel that had just come into the harbor to

supervise the ship's cargo inspection.

This move angered the customs officials

at the Custom House and they sent their young clerk, Juan B. Alvarado,

to try to persuade the Governor to remove the guard from the ship.

Governor Gutierrez refused Alvarado's requests and when the young

clerk began to push too hard, the Governor ordered him thrown

into jail.

But before the order could be executed,

Alvarado bribed his way past the guards and fled to San Juan Bautista.

There he met a Tennessee backwoodsman by the name of Isaac Graham

who listened to his story and agreed to help the young Alvarado

overthrow Gutierrez. To enlist Graham's aid, Alvarado promised

to declare California an independent state and to also create

new laws permitting foreigners to acquire lands without becoming

Mexican citizens. Graham called together fifty foreigners to join

Alvarado, Castro, twenty-five Californians and a few Native Americans

for a march against Monterey.

On November 3, 1836 these forces under Jose

Castro entered Monterey, captured the Castillo, and trained its

guns upon the Presidio commanded by Gutierrez. From that vantage

point, the occupiers demanded that Gutierrez surrender the town.

Alvarado and Graham spent two days exchanging propositions. Finally

a demand was make to Gutierrez to surrender within two hours.

When an answer was not forthcoming, Graham and his comrades seized

the Castillo. Castro ordered a shot from a four-pound brass piece

fired from the battery to remind Gutierrez that his bargaining

position was somewhat precarious. By sheer luck the cannon ball

went through the roof of the Governor's residence sending his

supporters as well as roof tiles flying in all directions and

eventually resulting in his surrender the next day. The apparent

dash and heroism of this event is somewhat qualified by the following:

"the occupiers captured the Castillo because it was not defended,

the cannon ball that hit the presidio was the only one in the

Castillo that fit any of its guns and gunners Balbino Romero and

Cosime Pena fired the cannon after taking fifteen minutes to read

up on artillery practice. Following the shot that brought down

a government, the instigators of this little revolution took possession

of the presidio, exiled Governor Gutierrez to Mexico, appointed

Juan Bautista Alvarado governor, and properly celebrated the entire

fiasco with a series of fiestas."

Alvarado declared California a "free and sovereign state" within the Mexican Republic with autonomy in its personal affairs. But he failed to create the new laws permitting foreigners to acquire lands without becoming Mexican citizens. Alvarado was the first Monterey-born Governor of California. In a short time counter-revolutionary forces began to gather in the south.

Perhaps the best description of the Castillo

during this period is from the pen of British sea captain Edward

Belcher in 1837 in his Narrative on pg. 136:

"The adobe or mud brick battery remained from a previous visit and has been newly bedaubed during the late ebullition of independence. The fortifications, of which plans must not be taken, consisted of a mud wall with three sides, open in the rear, with breast works about three feet in height with rotten platforms for seven guns the discharge of which would annihilate the remains of carriages."

Another visitor in 1837 was Abel du Petit-Thouars who visited Monterey in the ship Venus. He reported in his account entitled Voyage of the Venus: Sojourn in California, pg. 9 that:

"This battery was originally designed to cover the roadstead and to prevent landings. Today its dilapidated condition renders it useless. It hardly serves to render the customary salutes. The guns of different calibers with which it is armed are in an unbelievable state of deterioration and the mountings, like the platform, are entirely rotten."

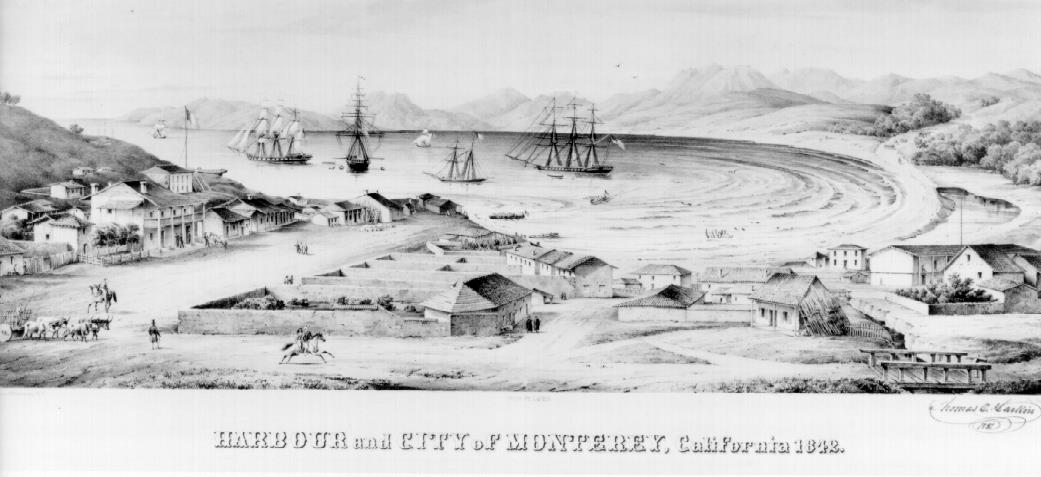

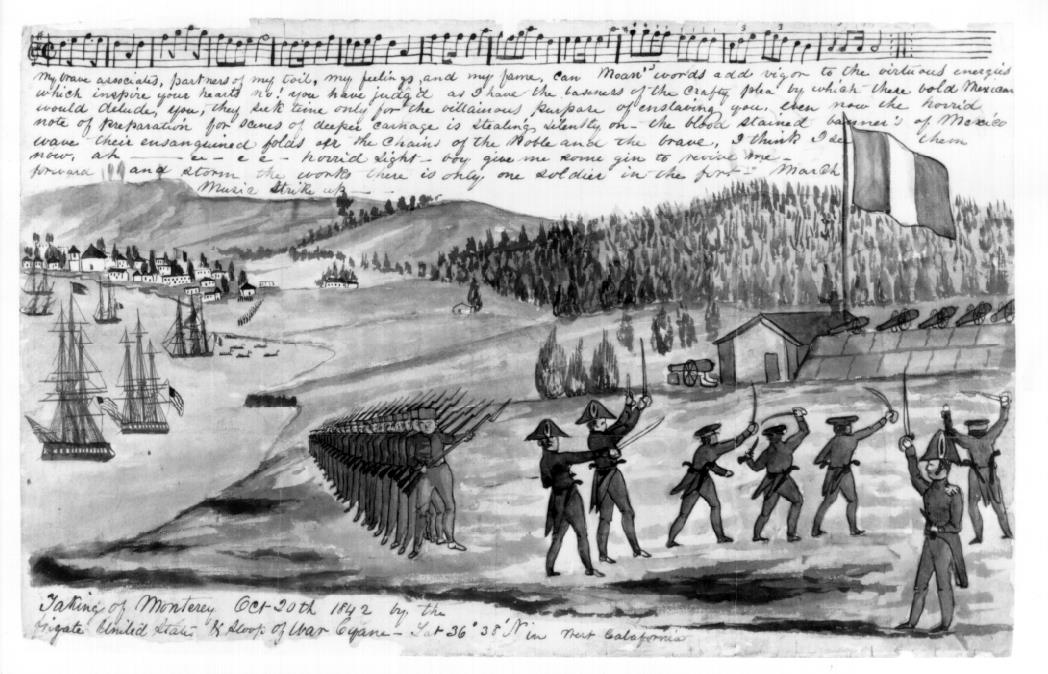

One of the most famous encounters with the

Castillo occurred on October 19, 1842. On that day the American

west coast squadron of the United States, Cyane, Yorktown, Dale,

and Shark under the command of Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones

took actions to occupy Monterey. Jones was under orders to conquer

and occupy California the moment that hostilities broke out between

the United States and Mexico to avoid preemption of the territory

by England. Jones believed the two countries were at war when

he sailed for Monterey early in October. On the 19th he sent an

officer ashore to demand surrender of the post. Governor Alvarado

was given until the 20th to consider the demand. In the meantime

Alvarado requested a report on existing defenses from Mariano

Silva, Comandante of the Presidio. Silva replied that they were

of "no consequence as everyone knows." The capital had

only twenty-nine soldiers, twenty-five militia and eleven cannon

lacking ammunition and 150 muskets. Alvarado surrendered at 9

a.m. At 11 a.m. Jones sent a troop of men to occupy the town and

raise the American flag over the abandoned Castillo.

At least two Americans witnessed the event, however, and they

later indicated that things were more lively at the Castillo than

Jones reported. Richard Maxwell, a physician with the fleet, accompanied

the group of marines to the Castillo. In his Visit to Monterey

in 1842, pg. 25, he describes the events as follows:

"We were landed from boats at the foot of a ravine about twelve feet wide, leading up directly to the fort about four hundred yards distant and marched up six abreast. On reaching the summit of the hill, about twenty yards from the fort, we found nine lone brass guns concealed by green branches of trees, put in order of threes, above each other, commanding the whole ravine, these guns loaded with copper grapeshot and escopette balls, all primed, and the matches burning within a few inches of the powder and the linstocks lighted and at hand. In taking possession of the fort, we immediately unloaded these guns, and removed them to the breastworks again. Every gun had a name - Jesus, San Pedro, San Pablo and other saints."

This description contrasts so sharply with Silva's report to Alvarado

that it might be dismissed as the exaggeration of an excited observer.

But there is corroborating evidence from the irreverent gunner

of the Cyane, William H. Meyers. His comments appear in Extracts

from Ms. Journal of a Three Years' Cruise, by William H. Meyers

Aboard Cyane by Charles Roberts Anderson, Ed., pg.104. Meyers

wrote:

"The fort mounted 13 guns and one not good for much, making 14. Plenty of powder, iron and copper shot, round, grape and canister."

Midshipman Alonzo C. Jackson, who accompanied the landing force, described the captured fort as follows:

"The battery of the fort consisted of 14 long brass and iron guns, with which an effectual resistance might have been made had they been properly handled. We found in the magazine about a ton of powder, with any quantity of copper and iron shot. As soon as we had possession of the fort we went to work to prepare the fort for an attack from the inland."

Had the Mexicans wanted to defend themselves,

there could have been a lot of dead Americans at the Castillo

in 1842. Under the command of Lieutenant Dulany, Midshipman Jackson

and the others they converted the magazine into a sleeping apartment

for the officers and dubbed their new position Fort Catesby.

On the following day, October 21st, Commodore

Jones realized that he had made a colossal blunder. A survey of

the local government records and the assurances of Thomas Larkin,

the American Consul, convinced him that a state of war did not

exist with Mexico and that he had invaded a friendly nation by

mistake. The landing party was withdrawn immediately, the muskets

returned to the garrison, and the Mexican flag run back up the

flagpole to the accompaniment of salutes by the American fleet

and the Mexican battery. Commodore Jones retrieved the diplomatic

situation at least partially by tendering an apology to the Mexican

Governor Micheltorena, who had prudently returned to Los Angeles

on hearing of the landing, and who replied to the apology by arranging

a formal ball in honor of Commodore Jones.

Friendly relations were in fact restored

to the point where, on the 25th of October, the United States

even delivered to the Mexican garrison at Monterey 95 pounds of

gunpowder to replace the powder used by them in firing salutes

during the changing of the flags. As it turned out, the Mexican

garrison profited slightly from the exchange, as this was twice

the amount of powder actually expended. The American fleet remained

in the Monterey harbor for an extended stay.

Two years later the French traveler from the Mexican Consulate, Duflot de Mofras, visited Monterey and records his observations at the Castillo in Travels on the Pacific Coast Vol. II, pg. 212 as follows:

"A small barbette battery known as El Castillo, stands on the west side of the anchorage, a few miles offshore. On the sea approach, its sole support is a small earthen embankment, 4 feet high. In the vicinity are a crumbling building inhabited by 5 soldiers and a small shack used as a powder magazine. The battery has neither moat nor counterguard, and can be readily approached on all sides since it is on a level with the surrounding land. In conjunction with the presidio its situation is strategic, for El Castillo properly built and equipped could sweep with its guns any ship that approached moorings.

The ancient gun carriages, the two or three hundred copper cannon balls, the trucks, the ammunition chests of old Spanish material, all lie abandoned on the ground. The defense consists of 2 useless brass pieces, a brass falconet, 2 twelve-pounders, a sixteen-pound gun mounted on half-rotten gun carriages, and 2 pieces of eight, mounted on cartwheels. During public celebrations the latter, drawn by oxen, are used to fire off volleys and salute warships. Years ago these pieces, as well as those at San Diego and Santa Barbara, were cast in bronze in Peru or Manila, and bear the insignia of Spain with the inscription, Real Audiencia de Lima o de Filipinas.

Opposite the battery stands the flagstaff, visible to ships entering the harbor. Obviously this so-called castle is incapable of withstanding attacks and its sole function is to reply to cannon fired during fogs by ships searching for anchorage. As a matter of fact the Spaniards were wise enough to establish a small battery near Point Pinos, but few traces of this now remains."

From this report we learn that the Castillo was remodeled with

a barracks and a casemate for powder. The temporary battery at

Point Pinos is mentioned. And the existence of bronze cannon at

San Diego and Santa Barbara are verified.

This evidence indicates that the Castillo

was considerably enlarged sometime after the Bouchard attack,

although it is unclear exactly when these improvements were made.

It appears that the Meyers' watercolor sketch was correct. The

battery's two gun platforms had been extended more than thirty

feet in each direction to mount more firepower toward the bay

anchorage. Two other additions were clearly indicated, several

small stone magazines had been built along the platform and perhaps

most notable of all an adobe wall had been constructed to close

off the vulnerable rear approach. An adobe wall was also constructed

along the front of the Castillo at the hillside facing the harbor.

It would seem that although the Castillo

was reviled by most foreign observers, in peak condition and adequately

manned it possessed a destructive potential of note among Spain's

frontier fortifications. It is thus possible that Monterey's defenses

were considerably stronger than Silva reported and it may well

be that Alvarado simply did not choose to oppose the American

invasion and occupation.

In the summer of 1844, Governor Manuel Micheltorena

had all serviceable cannon, powder, and munitions moved inland

to Mission San Juan Bautista for the long expected war between

the United States and Mexico. Those armaments may have been abandoned

there, for several cannon were later recovered by American troops

at that site.

When the Americans again returned to Monterey

for good in 1846, they developed their own fort further up the

hill called Fort Mervin. Over the years the Castillo and its location

disappeared. As with the Presidio, interest in the history and

actual existence of the structure of the Castillo led to a search

for its location. Historians were pessimistic about finding remains

of the Castillo since the bluff on which it once stood had been

eroded by railroad and highway construction as well as military

building. This, plus weathering, made it quite possible that nothing

but a few stones and melted adobe would remain. It was felt that

the only way to prove whether the Spanish site was still there

was to undertake an archeological investigation. This was done

in 1967 through the National Park Service, using state funds remaining

from a title and land study. A crew of archeologists from the

Central California Archeological Foundation under the direction

of William E. Pritchard was hired to do the excavation.

The archeologists started excavating an

area on top of the bluff where tradition said the Castillo had

been. They encountered evidence of construction about a foot below

ground during the first few days. The Castillo, which has proved

much larger than originally thought, was an L-shaped gun platform

constructed of adobe brick and rock. It is about eight feet thick

and three feet high; originally it may have been five or six feet

above the surface. The north wing has been almost completely exposed

and its dimensions are about 41 feet from the apex to the end.

At least six rooms have been found on the west end of the north

wing, making its overall length more than 105 feet. The remaining

adobe brick is in good condition, as are the breastworks, which

were constructed of rock, rubble, and adobe mortar outside the

brick platform.

The inside features of the fort are also

well preserved. A rock catwalk inside the north gun platform is

still in good repair. A flagstone "bridge" or secondary

platform joins the two brick wings at their apex. This bridge

is covered with the remnants of a crushed granite floor plaster.

The inside floor area between the two wings seems to have been

covered with large rounded boulders, but no remnants of a smooth

floor were found.

Test excavations have exposed the walls

of a large, 26x33 foot building on the south side of the site,

which has been identified as the barracks shown in the Meyers'

drawing in 1842.

The Spanish built the Castillo on a Native

American site covering eight to ten acres. Materials have been

found as deep as nine feet dating to 1500 B.C. A burial site has

been located containing two adults and four children. After thoroughly

exploring the site of the Castillo, it was covered by plastic

and buried.

The U.S. Army at the Presidio and the City of Monterey pledged to leave the site undisturbed. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The author has visited the site a number of times in the past 20 years, the last time in 2001. It appeared to be undisturbed then.

References: used for the Monterey Castillo are as follows: History of California by H. H. Bancroft, Vol. I, II, III; Old Fort Hill by Margaret B. Adams; El Castillo de Monterey, Frontline of Defense by Diane Spencer-Hancock and William E. Pritchard; Background Information on El Castillo de Monterey by the Colonial Monterey Foundation; A History of the Presidio of Monterey 1770 to 1970 by Kibbey M. Horne; Excavations at Monterey by News and Views, Department of Parks and Recreation; A Pictorial and Narrative History of Monterey, Adobe Capital of California 1770-1847 by Jeanne Van Nostrand.