During a recent

Clarksburg bridge game, talk turned to a nearly forgotten piece

of the town's history: the unlikely source of farmhands during

the labor-short war years.

During a recent

Clarksburg bridge game, talk turned to a nearly forgotten piece

of the town's history: the unlikely source of farmhands during

the labor-short war years.

Prisoner of War Camp located at Clarksburg,

California, reported as a branch camp of Stockton, California.

- per Report on Prisoners of War, Office of The Provost Marshal

General, 1 November 1945. Not found on list of Prisoner of War

Camps (Discontinued) - per Report on Prisoners of War , Office

of the Provost Marshal General, as of 1 December 1945. The camp

held 249 German prisoners who were used for agricultural labor.

Think of German soldiers during World War II and you think of the enemy. But Yolo County farmers who depended on German prisoners of war to work the fields here remember them fondly.

The German POWs served as farmhands during a time when most fit, young American men were off fighting the war. They were housed in three farm labor camps in Yolo County: two in Clarksburg (the first and the last established compounds) and one west of Davis.

When Maj. Lester Heringer was discharged from the U.S. Army Air Corps on Feb. 11, 1946, he never would have guessed the task that was going to be asked of him back home. Now 94, he was in his early 20s then, and was eager to return to farming after spending five years in the military.

But the Yolo County powers-that-be had different plans for him, given the labor shortage that was plaguing agriculture. He was asked to become head of a farm labor camp modeled after the county’s two previous facilities, and to set it up on a large plot of land that he owned.

As with the other compounds, the Army pledged to supply all the necessities, such as food and shelter. This camp would operate on a contract basis, allocating labor to farmers who were in desperate need of it within a busable proximity to the compound.

Ten acres of land were converted into a farm labor camp along Clarksburg’s Elk Slough by April 1946. It was outfitted with enough Quonset huts to house 550 German prisoners, approximately double the number of the men at the Clarksburg and Davis camps that came before it.

The unconfirmed mythology to these particular prisoners is that they were part of the Afrika Korps, an expeditionary force that marched through Libya and Tunisia during the campaign for North Africa. These troops were led by Nazi Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

Heringer found the prisoners he was in charge of to be self-sufficient, civil and compatible enough for the job.

“They took care of each other,” Lester said of his men, who cooked their own meals and maintained their living quarters. Most were 30 years old or younger, and some were still in their late teens.

“They were actually a good bunch of young fellas,” Heringer said, then paused before adding, “but they weren’t here because they wanted to be.”

Despite not being here of their own volition, the German prisoners made the best of it, staging variety shows with regularity.

“A little singin’ and a little dancin’,” Heringer said with a smile when asked what their performance would consist of. “Just like the Americans. Actually, you’d never know they weren’t American, except most couldn’t speak English.”

There were a few, he added, that did know the language. Heringer said a small amount of fraternization between the prisoners and the local farmers was not uncommon, though the military officially prohibited it.

“They got tied to the Americans pretty well,” he said. “I don’t think they expected things to happen the way they did, but that’s beside the point.”

By that, Heringer means that weeding, sowing and harvesting crops wasn’t what they thought they’d be doing. But that didn’t stop them from working hard in the fields.

One of the only problems Heringer recalls was in June of 1946, when a group of prisoners organized a sit-down strike while working a contracted farmer’s sugar beet fields.

Heringer was called in to mediate, but he wasn’t successful, given the language barrier. Not long after, a high-ranking detained German official arrived from an Army depot in Stockton, who solved the problem with some “verbal coercion.”

What the man said to get rebelling prisoners back to work was not clear to Heringer, but he did say he heard the German word “schwein” (which translates to pig) used quite liberally.

But the German prisoners were treated quite well on the whole. Researcher Douglas Brown, in his manuscript “The German POWs: Farm Labor Branch Camps in Yolo County,” relates a story from the late William Lider, a lifelong Yolo County farmer who had contracted the prisoners for work. Lider told Brown about a guard from the Davis farm labor camp mislaying his rifle; one of the prisoners found it and kindly returned it, rather than using it against his captor.

The compound that Heringer managed differed from the other two farm labor camps in the region in that there were no fences, guard towers or military men stationed there.

But even without those precautions, the prisoners apparently caused no trouble. Brown’s research indicated that there was only one rather innocent case of escape, in which two men fled but returned shortly thereafter. One was at a bar; the other at a brothel.

The first Clarksburg camp, activated in May 1945, and the Davis camp at Straloch Farm, established in July 1945, were more secure. Brown described both as being the Army standard: Two tall guard towers loomed over the front gates, acting as sentinels at the only entrance to a compound otherwise surrounded by barbed-wire fencing.

Not many details were chronicled about either of these camps, but an article in a 1945 edition of The Davis Enterprise reported that the prisoners of the Davis camp were accompanied by guards to work. When they returned, they were “locked in the compound, and soldiers (were) placed in towers to watch all through the night.”

But there were certain standards that needed to be upheld for the POWs: The Geneva Convention of 1929 established that the living quarters of prisoners had to be comparable to those of America’s own military domiciles.

Prisoners also were required to be paid comparable salaries to that of other farm laborers. All three camps in the area reimbursed prisoners at a rate of 90 cents per day (equal to an estimated $11.68 today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ online inflation calculator).

Payment came in the form of coupons that could be exchanged at a mobile trading post for snacks, toiletries and other items. Beer and cigarettes — which, according to Brown’s manuscript, were popular choices for prisoners — were no longer being offered by 1945.

Although the war ended in Europe in May 1945, more than 350,000 German prisoners were being held in the United States, and were not freed back to their homeland until well into 1946. The final Clarksburg camp ceased operation in late June 1946, the termination date set by Congress.

The three farm labor camps in Yolo County were open only a total of 18 months, but that was enough time for the prisoners to leave an impression on Yolo County’s agricultural community.

“They were some of the finest workers that I’d ever seen,” Heringer said. “They were there to work our fields when most of our boys were gone, and were a great help to us in that regard.”

Source The Davis Enterprise

8 November 2013

During a recent

Clarksburg bridge game, talk turned to a nearly forgotten piece

of the town's history: the unlikely source of farmhands during

the labor-short war years.

During a recent

Clarksburg bridge game, talk turned to a nearly forgotten piece

of the town's history: the unlikely source of farmhands during

the labor-short war years.

During World War II, Clarksburg's crops were tended by German prisoners of war, some of the 425,000 German prisoners interned at 511 camps in the United States as the war drew to a close.

Indirectly, they were helping the U.S. war effort. Many liked the land where they toiled, and some, after returning to their destroyed country, decided to come back for a fresh start here.

There's no question farmers needed their labor. According to a March 5, 1945 article in The Bee, California farmers, with their farmhands fighting overseas, needed 20,000 Germans for the harvest season. Another story noted that working the men here would ease the burden of guarding them overseas.

The two camps the government built in Clarksburg were part of a group of 10 in the area. Bob Heringer, whose brother ran one of the camps, said he returned to the area in 1946 after fighting Nazis, to find German soldiers hard at work on American soil.

"I had a young daughter -- just 3 years old -- a blond, blue-eyed girl," he said. "These young men were hoeing sugar beets just south of the house. They were so homesick when they saw her that they cried.

"Whenever I got feeling sympathetic, I remembered that I fought these people."

Lester Heringer lives on the grounds of what once was one of the Clarksburg camps. Standing beneath oak trees on the lawn behind his house, Heringer, 83, remembered the events of 46 years ago.

"This is where the barracks were," he said. "And at that end was the mess hall and the cook shack. We didn't have any fences for them. Didn't have any guards, either. The Germans didn't want to leave. They liked it here."

Just after Heringer's discharge from the U.S. Army Air Corps, where he'd risen to the rank of major, local beet growers persuaded him to run the camp. For camp housing, Heringer and farmers trucked in portable barracks from Fort Ord in Monterey County. Helping smooth the way was American Crystal Sugar Co., which was the representative organization contracting with the government for the farmers.

A German leader controlled the camp's 550 prisoners. Heringer simply presented him with times and numbers of men needed for a day's farm work.

Invariably, the Germans marched in on time from the POW camp on Elk Slough to Netherlands Road. There, they got onto trucks and were taken to farms for nine-hour shifts.

For their work, the prisoners were paid 90 cents a day in scrip for snacks and toiletries.

Heringer said the prisoners worked the sugar beet fields, wielding the now-outlawed short-handled hoe.

"They would bend over with that short-handled hoe and wouldn't straighten up all morning," he said. "You talk about efficiency. Everything was like a garden when they were through."

Heringer recalled only one time when the prisoners would not work, a June day when they sat down in a sugar beet field and wouldn't get up.

Heringer, who did not speak German, never did find out what was bothering them. He called POW officials in Stockton to intercede.

Heringer recalled that the Stockton official repeatedly used the word "schwein" in speaking to the POWs. "He called them pigs and they were up to work in five minutes."

Heringer is left with only memories from that time -- and a plate carved from oak sent to him from Germany by a repatriated POW.

The German prisoners were carefully screened from the time they came from the East Coast.

"All the bad ones, the super-Nazis, were weeded out," said Douglas Brown of Penryn, a researcher who has studied Northern California German POW camps. "The West Coast got corporals or privates happy to be away from being killed."

One was Pvt. Joseph Roesch, a twice-wounded veteran of the Russian front who was captured by British troops in Africa and sent to the United States. He was held 15 months at Camp Beale near Marysville -- now Beale Air Force Base -- before returning to Germany after the war.

"Treatment was good," said the retired draftsman, whose thick accent remains. Now 81, Roesch lives in Live Oak, Sutter County. He returned to the United States in 1955 with the help of an American sponsor.

The barracks where Roesch lived are gone, along with most other traces of that time.

It was Brown's inquiries that prompted the bridge game reminiscences of the POW days and brought to light an almost forgotten part of Clarksburg's past.

Al Sandberg, the retired general manager of the now-closed Clarksburg sugar beet plant, had saved the labor contract for one of the Clarksburg camps after the plant was sold in 1994.

Alerted to the historical interest in the POWs, Sandberg retrieved the contract from a storage unit. Now a copy is on file at the Clarksburg library, another in the hands of historian Brown.

Brown recently completed two studies of German POW farm labor camps in Northern California. About 16 camps were still operating in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys as late as Aug. 16, 1945, although the war in Europe had ended in May.

One report details camps operated out of Camp Beale, which had satellite camps in Arbuckle, Chico, Davis, Windsor in Sonoma County, and Yountville in Napa County.

Brown's other report looks at Yolo County's camps: the Davis compound and the two Clarksburg camps. Little is known about the second Clarksburg camp, a short-lived compound established in 1945 a half-mile west of the sugar beet plant.

Not all the prisoners were involved in agriculture work. At North Highlands' Camp Kohler, an Army Signal Corps depot, about 500 German POWs did laundry for the military installations in the Sacramento area, eventually moving to McClellan field, Brown said.

In Placer County, the first 25 German prisoners arrived in 1945 to install fences and guard towers at Camp Flint. Prisoners there helped maintain grounds at the DeWitt Hospital.

Brown, retired from the California National Guard and California Air National Guard, said he hopes the Yolo County Historical Society will publish his report on the Yolo County operations. He has submitted his other manuscript to the California Historical Society.

Among those caught up in the spirit of Brown's research was Peggy Azevedo, a volunteer at the Clarksburg library, who searched archives in vain for photos from the POW period.

Meanwhile, Brown combed old newspapers and conducted interviews in Clarksburg looking for details of the period.

A Yolo County camp, for example, operated on a Davis farm and housed 250 men. A 5-acre compound with guard towers, was just south of the University of California, Davis, airport.

Brown says the university's avian research

building likely was then the camp dining hall.

Published 2:15 a.m. PDT Tuesday, July 9, 2002

|

|

|

|

| Army of the United States Station List | 7 April 1946 | Detachment (Prisoner of War Branch Camp), 3968th Service Command Unit (Stockton Sub-Depot, Benicia Arsenal) (ASF) |

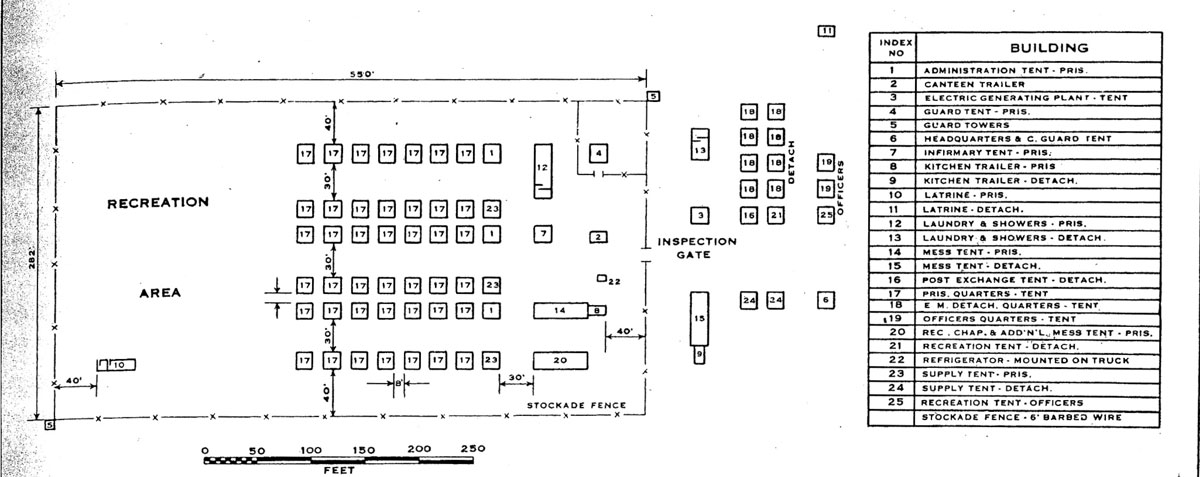

When the need for a branch camp was identified and certified as valid to the Army, it sent a team to select a site for the camp to fulfill the contractor’s requirements while still ensuring that the prisoners would be properly housed and secured. In many cases, few or no adequate buildings were available for prisoner relocation, so the Army developed a “mobile unit” package that could be set up quickly to temporarily house 250 POWs. It consisted of 42 tents, sized 16’ by 16’, allowing 6 or 7 men per tent. Seven additional tents of the same size were used as office and storage buildings. Four larger tents were used, one each, for mess hall, shower, latrine, and chapel/recreation purposes. This entire layout was set up in a compound bordered by a single wire fence that measured 282 by 550 feet (155,100 square feet). Portable guard towers, with searchlights, were placed at opposite corners of the compound to permit clear observation in the camp. Light poles were erected at intervals both inside and outside the camp. Each tent would have one or more light bulbs for night use.

The guard force for a branch camp of 250 POWs consisted of approximately 160 officers and men. It was composed as follows: 30 camp guards; 70 “prisoner chasers” who were the guards accompanying the POWs to and from work sites and monitoring them during work hours; 15 NCOs to oversee the guard force; seven support staff such as cooks and clerks; 33 drivers and mechanics; and five medics. Usually five officers were assigned including the camp commander, three camp officers, one supply and mess officer, one POW company commander, and one medical officer (if available).