EDITOR'S NOTE: This account was written by the son of one of the members of Company G, 184th Infantry Regiment. This appeared in the 11 November 2007 edition of the Chico Record.

This is the real true story of Chico, Calif.'s famous Company G, of the 184th Infantry Regiment during the World War II era.

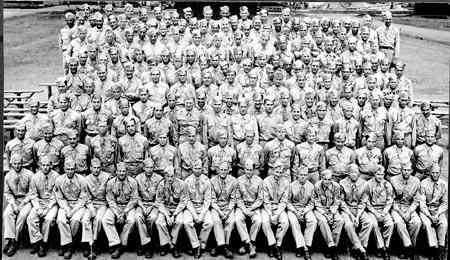

The men that formed Company G were comprised of mostly young kids that grew up with each other in Chico, and after high school joined the California National Guard. There were two sets of brothers in Company G. This Company G was like the real true "Band of Brothers" during "The War to End All Wars."

Company G of Chico had seen some of the hardest fought, and the most bloodiest of all military campaigns in the Pacific Theater of World War II.

The history of the 184th Infantry Regiment dates back to the 1800s. But this story being told of Chico's Company G starts with the history of America's 40th Infantry Division.

The 40th was born at Camp Kearney in San Diego on Sept. 16, 1917, in response to the nation's entry in to World War I. It was made up of the National Guard units from Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. It was soon decided that the new division's nickname would be the "Sunshine" Division.

When the division arrived in France in August of 1918, the Germans had just completed a series of offensives that started on March 21 and ended on July 15, 1918. These offensives were designed to destroy the American Expeditionary Force, before it could be fully constituted. They almost succeeded.

At the end of the war, the 40th ("Sunshine") Division had 2,587 members killed in action and 11,596 wounded. The division was latter reconstituted on June 18, 1926 with its headquarters in Berkeley. The division was organized pretty much as it was in 1917 with a lot of the units coming from Nevada and Utah. However, the "teeth" of the division was mostly Californian, with the Arizona and Colorado regiments replaced by two new California Regiments, the 184th and 185th.

For the most part, the normal peacetime routine existed until 1934. In November of that year, prisoners at the Folsom State Prison seized control of the main buildings and took several of the staff as hostages. The warden was unable to control the situation and asked the governor for the National Guard. Telephone calls and announcements over the radio were made. Theaters stopped their shows to announce, "... all National Guardsmen report to your armory."

The entire 184th Infantry Regiment, and supporting troops, under the command of Col. Wallace Mason, assembled and moved to Folsom. When the action was over, 11 inmates were dead and 11 wounded.

For the rest of the 1930s, the unit kept busy with their weekly evening drills and the "summer camp" at Camp Merriam between San Luis Obispo and Morro Bay. Several of the enlisted members who had joined the unit during the 20s and 30s would work their way through the NCO and commissioned officer ranks. One of the most notable was Sacramento dentist Roy A. Green, who joined the 184th Infantry Regiment as a private in 1918, and went on to be commissioned and command Company A, the 1st Battalion, and later the entire 184th regiment.

When France fell in the summer of 1940, President Roosevelt decided to bolster the Regular Army. There was the introduction of a peacetime draft, and in 1941, there was a general mobilization of the National Guard. The 184th, as well as the rest of the 40th Infantry Division mobilized on March 3, 1941.

They moved from their armories in Sacramento to their old training grounds at what was then known as Camp San Luis Obispo. Most of the regiment thought that they would be on active duty for only a year. However, on December 7, 1941, that all changed.

Within 48 hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 40th Infantry Division took defensive and security positions over a 350,000-square-mile area that stretched from Southern and Central California to Yuma, Ariz. and Salt Lake City, Utah.

The 184th regiment was moved to the San Diego area and took up defensive positions for the expected attack or invasion of the West Coast. While the rest of the regiment garrisoned areas such as Del Mar, La Mesa, and Lindbergh Field.

They were to remain there until April when they moved to Fort Lewis, Wash. and later the Presidio of San Francisco.

While at the Presidio, the 184th Infantry regiment was relieved from the 40th Infantry Division and attached directly to the Western Defense Command. In November 1942, Company G and the 184th regiment was attached to the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord, and later Amphibious Training Force 9. It was during this period that the regiment was reinforced and its title modified to the "184th Regimental Combat Team."

In July 1943, the 184th regiment left San Francisco bound for the Japanese held Aleutian Islands. The 184th arrived on Adak Island for training. On Aug. 15th 1943, Company G and the 184th Infantry Regiment embarked on there first campaign of the war. Operation Cottage, the retaking of the last Japanese-held island in the Aleutians commenced.

The 184th, augmented by the 1st Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, and with the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group on its right, made its first of many assault landings at Long Beach on Kiska Island. After an unopposed landing, the regiment found that the Japanese garrison had been evacuated by a large cruiser and destroyer force on July 28th.

The enemy had left in such a hurry, that they left mess tables still set with meals, and blankets soaked in fuel oil, but not lit. Nevertheless, Company G and the 184th did have the honor of being the only National Guard regiment to regain lost American territory from a foreign enemy in World War II.

When the island was declared secure, the division moved to Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, arriving in September of 1943. This was a welcome change for the men who just spent over three months on the Alaskan islands. However, it did not last long.

On Jan. 20, 1944, the regiment left Hawaii bound for the Marshall Islands. Company G's and the 184th's second campaign of the war was the landing on the island of Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands.

Kwajalein Atoll had been Japanese territory for decades. As such, they had many opportunities to build a complex system of fortifications on the island. On Feb. 1, Company G and the 184th Infantry along with the 32nd Infantry Regiment assaulted the heavily defended island.

When the battle for Kwajalein was over, approximately five days later, more than 8,000 Japanese, members of the 61st Naval Guard Force, were dead.

Gen. George C. Marshall, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, later said that the operations on Kwajalein were the most efficient of the war. Once again, Company G and the 184th achieved another first. They were the first National Guard unit to seize and hold territory that Japan held prior to the start of the war.

With the island secure, the 184th re-embarked on to their transports and returned to Hawaii for rehabilitation and more training. On Sept. 15, 1944, they departed Hawaii, bound for Eniwetok Island. Initially, this was to be a staging area for the invasion of Yap Island, but when they arrived, they found that the operation was canceled in favor of a larger landing: the liberation of the Philippines.

On the morning of Oct. 20, 1944 the 184th Infantry's third campaign of the war was the landing on Leyte Island of the Philippines.

The 7th Division with the the 184th hit the beaches near Dulag on the east coast of the island of Leyte. With the beachhead secured, they moved inland.

The island provided the Japanese with an ideal defensive terrain. Leyte is a large island, covered with mountains, rain forests, and swamps. The Japanese 34th Army, consisting of four divisions, including the infamous 16th Division that was credited for the "Rape of Nanking" and the "Bataan Death March," was the primary opponent on Leyte.

Company G and the 184th pushed on through the Dulag Valley experiencing high casualties. When the Japanese counterattacked the 32nd Infantry Regiment, which had spread out along the Palanas River, the 184th was sent to reinforce them. Several attacks were repulsed and the enemy was driven into the bamboo thickets. This action later became known as The Battle of Shoestring Ridge.

The division then moved to Baybay, and the 184th started a drive from Damulaan towards the port of Ormac. They then seized the town of Albuere and had joined up with soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division, which had landed near Ormac on the other side of the island. When the 7th division left, they were credited with inflicting more than 54,000 enemy deaths.

On April 1, 1945, Easter Sunday, Company G and the 184th would start their fourth, final and bloodiest campaign ever, the Battle of Okinawa — the largest and most-costly battle in the Pacific Theater in the history of World War II.

Okinawa was an island 70 miles long and eight miles wide, 60 times the size of Iwo Jima. Okinawa was the last of the Japanese army's strongholds, with more than 110,000 well-trained troops.

The Japanese 32nd Army were the veteran 62nd Infantry Division out of China, the 24th Infantry Division from Manchuria and the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade from the home island of Kyushu. Another 10,000 troops had been put together from Japanese Navy personnel based on Okinawa and the nearby islands.

In addition, the Japanese Army had one tank regiment, three artillery regiments, consisting of two 150 mm howitzer regiments and one of a mixture of 75 mm to 120 mm guns. Also there was a regiment of the giant 320 mm mortars that wreaked havoc among the Marines on Iwo Jima.

On that Easter Sunday, four divisions landed on the central part of the island on the western shore. The 7th Infantry Division and the 96th landed near Kadena on the right, the 1st and the 6th Marine Divisions landed on the left near Yontan. The first objective for the 184th's Company G was to take Kadena Airfield. An hour later, the 6th Marine Division captured Yontan Airfield just north of Kadena.

Initially the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions were to clear the southern end of the island. Fortunately for these thinly spread forces, an expected counterattack did not occur. If it had, there was a possibility that they could have driven the invasion force back into the sea. Thus far, the Japanese had given little sign of their presence.

After the taking of Kadena, the 96th along with the 7th Division turned south, and the 96th followed the western shore with the 7th to its left on the eastern side.

On April 5th, the American troops moving southward on Okinawa would realize the Japanese resistance had begun. The Japanese concentrated their forces in the southern third of the island, taking advantage of a series of natural barriers formed by ridges and cliffs. Their first line of defense extended from Kakazu Ridge on the west shore of the island to Skyline Ridge on the eastern shore.

This first line of the Japanese defense was approximately eight miles across, from the western side of the island to the eastern shore. On April 9th with the assistance of massed artillery fire, Company G and the 184th captured Tomb Hill. By now, companies were losing 30 to 50 men per day. At this point of time it was taking the 7th Division seven days to cover 6,000 yards.

Meanwhile the 96th was having equally tough goings on the eastern shore, at a hill called Cactus Ridge. It took three days of frontal and flanking attacks to capture the hill. Their next objective was one of their bloodiest, a 1,000-yard ridge with a 280-foot crest called Kakazu Ridge.

On the way south, the men of the 7th and Company G of the 184th had secured eminences they would long be remembered, Castle Hill, The Pinnacle, Red Hill, and Triangulation Hill. But the 7th had paid for its gains, yard by yard, with more than 1,120 casualties and more battle to go.

On April 13th, the 96th Division was stalled on the western end of the first Japanese main defense line, and the 7th was stalled on the eastern end near Rocky Crags. In the nine days since the two divisions moved south, they had inflicted more than 5,000 enemy causalities, but had incurred more than 2,500 of their own.

On April 19th, the 27th Infantry had been brought out of the reserves to fight alongside the 7th and the 96th. The 27th Infantry was formally a National Guard unit from the State of New York. The 27th had recently seen action on the island of Saipan. Toward the end of April, American Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner took steps to put fresh muscle into the American force confronting the Japanese. The 1st and 6th Marine Divisions were brought down from the north of the island to help in the fight.

The last few days of April, the first line of defense for the Japanese finally fell after three weeks of bloody fighting. For the first three weeks in May, the Japanese 32nd Army held the advancing American forces along a rugged terrain which ran from the town of Yonabaru on the eastern side of the island, to the port of Naha on the western shore. This second line of the Japanese defense was known as the Shuri line.

The Japanese Commander General Mitsuru Ushijima took Shuri Castle, a 15th Century fort that had once housed Okinawa's feudal kings, and made it his personal headquarters for his 32nd Army. At this point of time the 6th Marine Division which was on the far western shore of the island was having its bloodiest battle, for a place called Sugar Loaf Hill.

This battle lasting nine days cost the division 2,662 men.

On the 21st of May the 96th Division had finally finished a 10-day struggle and their bloodiest encounter with the Japanese thus far, a 476-foot peak that was known as Conical Hill. Conical Hill had cost the American's 96th and the 77th Divisions 377 killed and more than 2,200 wounded.

These battles were fought against a Japanese heavy artillery armada made up of 150 mm Howitzers that were on tracks that they could roll out of large caves and fire on the advancing American forces.

On a rainy night, May 22, Company G and the 184th marched southward on the eastern shore toward the town of Yonabaru. The plan was to secure the eastern end of the road to Naha, and then another regiment, the 32nd, would swing westward on the road and complete the encirclement of Shuri Castle, the Japanese 32nd Army Headquarters. The plan was called "Checkmate."

But Okinawa's monsoon season had begun. Torrential downpours would continue for over two weeks. The American troops and tanks of the 7th Division would become bogged down, and at the mercy of the deep mud. But still with heavy fighting, by the end of May, the Japanese Army started to abandon its stronghold at Shuri.

On the 29th of May, the Marine 5th Regiment had taken Shuri Castle, and the Japanese slipped away to the southern tip of the island. There they would make their last stand, along the fortified hills which ran from Kunishi Ridge on the western shore, to the Yaeju-Dake Escarpment towards the eastern hills. This would be the last Japanese line of defense on the island of Okinawa.

By this time the plan was to have the three American divisions — the 7th Infantry on the east coast, the 96th Infantry in the center and the 1st Marine Division on the west coast — launch a hot pursuit south at the retreating Japanese Army.

On June 8, Hill 95 on the eastern side of the Japanese line was the target for the 7th Division. Heavy gunfire from caves on the rocky slope prevented a successful assault. On June 12th with the help of the 713th Armored Flamethrower Battalion, Hill 95 was captured.

The 96th was having problems scaling a 300-foot ridge at Yaeju-Dake's cliffs, with heavy gunfire coming from more than 500 caves at the face of the cliffs. To the right of the 96th, the 1st Marine Division had their hands full with heavy fighting to take Kunishi Ridge, the western anchor of the last Japanese defensive line. A cave-by-cave battle took place to root the Japanese from their last major defensive positions on the cliffs of Okinawa.

On June the 20th, a regiment of the 7th Division reached the flat top of hill 89 near the southernmost tip of the island. Resistance was still strong, and flamethrowing tanks used nearly 5,000 gallons of napalm to burn Japanese snipers and mortar men out of their caves and coral crevices of the seaside hills.

The battle continued on for two more days with some of the remaining Japanese Army left committing hara-kiri.

June 22, was the official end of the campaign in Okinawa. The American flag was raised over army headquarters near Kadena Airfield. When the graves registration teams had finally completed counting all of the bodies at the end of this bloody battle, the figures told a story that came as no surprise to the fighting men.

Okinawa had been the bloodiest land battle of the pacific war.

The Japanese had lost approximately 110,000 men and 10,755 prisoners during the 83-day struggle for the island. The victory on Okinawa had cost the Army and the Marines 7,613 killed and 36,000 wounded.

The men of Company G, the 184th had seen

their last battle of World War II, and it was time to come home.