The arrival of Albert Sidney Johnston in Richmond, Virginia, in

mid-September 1861, created considerable excitement. His arrival

had been eagerly anticipated by his friend, Confederate President

Jefferson Davis, who quickly appointed him General and assigned

him to command the Confederate forces in "the West."

The story of his long journey from California, across the desert

South west to Texas, and then on to Richmond, has become almost

legendary. Most accounts of his journey mention that there were

others with him - generally referred to as "Johnston's escort."

Though, in effect, these others did "escort" Johnston

to the Confederacy, they were more than that. Their organization

had preceded Johnston's resignation from the U. S. Army by over

two months. They were members of a bona fide company of California

Militia - the Los Angeles

Mounted Rifles. As the only Free State militia unit that "went

Confederate," their story is unique in itself.

It could have happened only in California. In many respects, California could have been considered, though slavery was prohibited there, as a "Border State". Its American (or "Anglo") population was largely new to the State and hailed from both the North and the South. The "native" (as then termed) population of Mexicans had been citizens of the United States only since 1848 - a bare 13 years - and had not yet had time to develop any particular loyalty to the government of the United States. California was far from the government in Washington, and the nation's main centers of population. News from the East was slow to reach the State and government services few. Additionally, there were divisions within the State. In 1860, the legislature had passed a bill, signed by the Governor and approved by a vote of its citizens, to divide the State. What is now termed Southern California would have become the State of Colorado. With division of the nation anticipated, the Congress never acted upon the request.

On the eve of the Civil War, Los Angeles was a city of between

3,500 and 4,000 inhabitants. Its people were a mixture of Mexicans,

Indians, Americans (both Southern and Northern in origin) and

German Jews. There were only a few Chinese (mostly engaged in

laundering) and Blacks. The houses were all one-story, built of

adobe (sun-baked bricks) with thick walls and flat roofs. There

were very few two-story buildings - basically just the hotels

with their associated first-floor saloons. Though a long-established

center of population, Los Angeles was still a rough, frontier

town. Most men habitually were armed with both revolver and Bowie

knife. Even the clergy advised that it was "best to have

arms after dark". There were in those days fifty to sixty

murders per year. It could not be expected that such a population

under such circumstances would not involve themselves in the major

crisis of the day.

Even before any states had seceded, in both the North and the South, militia units were "activating" and volunteer companies being formed. In some states the militia was well-organized and functional, but in most the militia was little more than a social group or "paper" organization. In California, the militia was a sham. During the 1850's companies had been formed for one purpose or another but quickly died out. The Adjutant General had kept little track or record of them. With the crisis growing in the East, Governor John G. Downey issued a call for the formation of militia companies "to preserve order". Few of the companies formed in response to his call ever amounted to anything, but one that did was the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles.

In mid-February 1861, after the secession of several Southern

States, a petition was presented to Los Angeles County Judge Dryden

to "open a book" to enroll a volunteer militia company.

The petition was signed by seven prominent Angelenos. Joseph Lancaster

Brent was a wealthy attorney and former state legislator. Attorney

Meyers J. Newmark was scion of a leading Jewish mercantile family.

George Washington Gift was a civil engineer noted for a book on

California's complex land laws and had also represented the county

in the state legislature. Jose Antonio Sanchez was a baker and

a leader of the city's large Mexican community. German-born Joseph

Huber was a vinter. Alonzo Ridley was an undersheriff of the county.

The other signers were A. J. Henderson and Francisco Martinez.

Maryland-born Judge Dryden rapidly approved the petition and,

on February 25th, Gift announced the opening of the enrollment

book.

Enrollments proceded rapidly and with, according to best accounts, some 80-85 already enrolled, an organizational meeting for the new militia company was held at the Los Angeles County Courthouse at 7:00 PM on March 17th, 1861. Gift acted as chairman of the meeting and Joseph Huber, Jr., acted as secretary. The name "Los Angeles Mounted Rifles" was selected and officers for the company elected. Alonzo Ridley was elected Captain of the company. Northern-born, he had arrived in California some ten years prior and had been a trader among the Indians and then sub-agent to the Tule River band before being named Undersheriff for the northern portion of the county. Joseph W. Cattick was elected First Lieutenant. Los Angeles County Sheriff Tomas A. Sanchez and Samuel Ayres were elected 2nd Lieutenants. The four Sergeants were Tennessee-born policeman Robert A. Hester, California-born farmer Pedro Antonio Abila, Kentucky-born Jailer Francis M. Chapman, and New York-born housepainter Jospeh N. Chandler. Francisco Martinez, Lyman A. Smith, Rafael L. Bauchet, and Jospeh Huber, Jr., were elected as the Corporals.

There were 64 Privates listed on the initial (and only extant)

muster roll. (Refer to

Appendix for copy of this Muster Roll.) Among them were two

attorneys (Brent and Newmark; civil engineer Gift; two ranch owmers

(Carlisle and Rains - both sons-in-law of Isaac Williams who held

several large ranchos through his marriage into a noted Californio

family); laborers; miners; farmers; a wagonmaster for the U. S.

Quartermaster Depot; a saddlemaker, a cabinetmaker, clerks; and

a master plasterer. The most prevelent occupation was law enforcement.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff's Office must have been a-real

"hot bed" of pro-Southern sentiment. In addition to

Sheriff Sanchez, Undersheriff Ridley, Jailer Chapman, and policeman

Hester as officers and noncoms, there were at least two constables

among the privates. (Another undersheriff, A. J. King, though

not a member of the Rifles, was involved in pro-Confederate agitation

in El Monte.)

Ages ranged from the early twenties to the late thirties. Most

were from Los Angeles and its immediate area, though there were

a couple from El Monte, one from Santa Ana Township (now Orange

County), a goodly number from the Tejon area in the northern part

of the county, and ultimately one from San Diego County. The ethnic

composition of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles was a true reflection

of the community. "Sanchez" was the most common surname

and fully 10% of those on the Muster Roll had Spanish surnames

and had been born in Mexico (presumably California when it was

part of Mexico). The "Anglo" component included men

of both Southern and Northern origin as well as German Jews and

Irish immigrants. Ultimately, there would also be one Black man

affiliated with the company.

Military experience of the members was fairly

limited. Sheriff and 2nd Lieutenant Sanchez was a man noted for

bravery and had been a lancer in the Californio unit of the Mexican

Army that had defeated General Kearney at the Battle of San Pasqual. Private Gift had been

a Midshipman in the U. S. Navy during the Mexican War. Private

Carman Frazee had served in Jefferson Davis' 1st Mississippi Rifles

in that same war. A few others had probably also seen some service

- on one side or the other - in the Mexican War. All were, of

course familiar with firearms and riding. No doubt, like all so

many who went off to war in 1861, this familiarity and the hardships

of frontier or rural life and an ardent patriotism were considered

sufficient qualification.

From its inception, the Los Angeles Mounted

Rifles had. been known to be pro-Southern. Indeed, organizer Gift

and Captain Ridley both in later years acknowledged that the unit's

purpose was to serve the Confederacy. Initially, perhaps, there

had been some hope - even a real chance - that their service would

be in a seceded, or at least neutral, California. They were a

definite worry to Union authorities. In April, Brigadier General

Edwin V. Sumner, commander of U. S. forces in the State, wrote

the War Department about conditions in California. Of Los Angeles

he wrote that, "There is more danger of disaffection at this

place than any other in the State. There are a number of influential

men there who are decided Secessionists, and if we should have

any difficulty it will commence there." Though there were

many who wished to cause difficulty in California by raising rebellion,

clearer heads prevailed. Sheriff Sanchez on one occassion warned

off a rowdy group from El Monte who planned to disrupt a Union

meeting in Los Angeles. Lawyer Brent counseled that though there

might be some initial success against the government, that U.

S. control of the seas and distance would prevent any lasting

success and that those who would like to really do some good for

the Confederacy should make their way east and join its armies

there. The Rifles did not immediately head east for Texas and

the Confederacy though. such a journey would require detailed

planning and preparation - and the Company would first have to

be armed.

Captain Ridley was vigorous in his efforts to obtain from the State the weaponry needed by the Company. On March 9th, only two days after organization, he wrote California Adjutant General William C. Kibbe requisitioning 80 rifles, 80 Colt six-shooting pistols, and 80 sabers. He suggested to Kibbe that 40 of the needed rifles could be found at the Los Angeles warehouse of Banning and Hinchman consigned for a San Bernardino County militia company. Ridley stated that since that organization was defunct, those rifles should be diverted to his unit "... where they would be put to good use." He also asked for 80 sabers previously earmarked for the inactive City Guard and for 60 sabers issued to Captain Juan Sepulveda's Lanceros de Los Angeles. Apparently, he had copied Governor John G. Downey (a Los Angeles resident), for on April 3rd he wrote the Governor a letter of thanks, stating that Banning and Hinchman had honored the Governor's order to deliver the rifles to him. At the same time, he again asked for the rifles and sabers of the Los Angeles City Guard. In truth, he already had some of these rifles. Eleven had been stored at the County Jail and Ridley requested reimbursement of $26.00 he had spent to have them repaired and put into serviceable condition. Another 25 percussion rifles, which had been issued for the Southern Rifles (a defunct Unionist unit) on deposit with Sheriff Sanchez, were likewise diverted for the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles. Unmentioned by Ridley, Sheriff Sanchez also had custody of a small cannon earmarked for a Santa Barbara County militia unit.

News of Fort Sumter and the beginning of the war on April 12th

did not reach Los Angeles until April 24th. This news removed

any hope that the Rifles would be able to serve the Confederacy

in California. Means by which the Company might join with Confederate

forces began to be explored. Former Navy man Gift preferred a

sea route. Ridley believed that the better route would be across

the deserts to Texas. This route had already been taken by individuals

and small parties and would enable a larger portion of the Company

to join the Confederacy - and to take off with them all their

California State-owned weapons. On the other hand, planning for

such a large group as the 80-plus Rifles would be difficult to

conceal from nervous and watchful Union authorities.

Ridley himself made the majority of arrangements for a departure

to Texas. He traveled hundreds of miles around Southern California

and expended considerable personal funds in this effort. His plans

would have gotten most of the Company to the Confederacy. Circumstances

arose, however, which dictated a more rushed departure. There

were in Los Angels several former officers of the U. S. Army who

had resigned their commissions and were awaiting acceptance of

their resignations before returning to their homes in the South.

Then there was Albert Sidney Johnston, said by some to be "the

finest soldier on the North American continent." He was a

West Pointer, veteran of Indian Wars, the Texas War of Independence,

the Mexican War, the "Morman War" in Utah, and most

recently commander of the U. S. Army's Department of the Pacific.

His intentions were cause for real concern on the part of the

Union authorities. There were numerous rumors and great fears

that Johnston would use.his position to force California and other

far western areas out of the U. S. and onto the side of the Confederacy.

High minded and true to that code of honor prevalent among officers

of his day, Johnston neither had intended nor attempted any such

thing. He did resign his commission but, until relieved by Sumner,

loyally fulfilled the obligations of his office and even took

actions to prevent others from aiding the Confederacy. Upon handing

over his command, he moved with his family to Los Angeles where

his brother-in-law, Dr. John Griffin, resided. His intention was

probably to "sit out" events as a neutral. Union authorities

however kept him under close observation and it was soon obvious

that he would have to "head South" before Unionist fears

and suspicions led to his arrest.

Ridley encountered Dr. Griffin one day upon the streets and offered

him the services of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles in helping

Johnston reach the South. The next day, Ridley and Johnston met

in the Doctor's office with the General accepting the offer. Under

suspicion and constant watch, it was unsafe for Johnston to participate

in plans or even in the necessary preparations for his own departure.

This task was therefore delegated to Randolph Hughes. Hughes was

Johnston's long-time friend, servant and bodyguard. He had been

a slave but, wanting to accompany Johnston to the free state of

California, had been freed in the later 1850's. It was "Ran",

as Johnston called him, who assisted Ridley in the final preparations

and collected those items that would be needed by Johnston and

himself for the journey - an ambulance (a wagon with springs),

a team of mules, and a Mexican pack mule.

The plan as originally conceived by Ridley, had been for the Rifles to leave for Texas on June 30th. The addition of Johnston to the party necessitated greater urgency. Departure was moved up to the 17th but word was circulated that it had been delayed to the 25th. It is doubtful that this ruse deceived Union authorities as to the actual departure date. At least the Captain in charge of the U. S. Quartermaster depot in Los Angeles - Winfield Scott Hancock - was not deceived. On the evening before the departure, he gave a farewell party for the resigned officers who would accompany the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles. Some years after the war, Mrs. Hancock described this as a very moving and heart-wrenching affair, particularly for her husband and his close friend, Captain (Brevet Major) Lewis Addison Armistead, who had only recently been commander of the army post at San Diego. (This party has been dramatized in the book Gods and Generals.) Mrs. Hancock did not name all of those attending - only herself and her husband, Armistead, and General and Mrs. Johnston. Most presumably the others were the resigned lieutenants -.who did make the journey with the Rifles. Most likely Hancock's two children put in an appearance as did Armistead's son who was in California visiting him at the time. It is somewhat incredible that Johnston would have attended for the Hancock residence was across the corner from the headquarters of Col. James H. Carlton who was commanding Union troops now stationed in Los Angeles (and later commanded as Brigadier General the "California Column"). Some accounts have placed future Confederate generals George Pickett and W. S. Garnett at the party but this is erroneous as they did not even pass through Los Angeles on their routes to the East from areas further north.

Having learned that Johnston and himself were to be arrested on

charges of treason, Ridley had again advanced the date of departure.

In the early morning of June 16th, he, Johnston, and Hughes left

Los Angeles for the Chino Rancho about thirty miles east of Los

Angeles. Himself a Private in the Rifles, ranch proprietor Robert

S. Carlisle was ready and willing to assist in the effort. Here,

Ridley left Johnston to go and inform others of the revised schedule

and of plans to assemble at Warner's Ranch, an important stop

along the Overland or Butterfield Stage Route. At Chino, Private

Carman Frazee joined the General to act as his guide to Warner's.

Carlisle posted his vaqueros along the route to keep watch for

any Union troops and to warn of any possible pursuit. Private

John Rains of the Rifles was the then owner of Warner's Ranch.

He had instructed his ranch manager to slaughter cattle and prepare

meat for the Company's journey. Most of the group that would make

the journey had assembled there by June 26th. Captain Ridley offerred

the command of the group to Johnston, as a Brigadier General outranked

a Captain. Johnston declined saying that he was no longer a General

and only a citizen who would serve under Ridley. The resigned

lieutenants (Armistead had not yet joined the group) followed

Johnston's lead in this matter becoming, in effect, privates of

the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles. Even though Ridley and the others

would during the journey often seek and defer to the counsel of

Johnston, it was Captain Ridley who was in command and organized

the line of march, set the watches, and the like.

Johnston wrote his wife that the party was of sufficient size

and well-armed to have little fear of capture. They were indeed

well-armed. In subsequent months and years, there would be many

recriminations among General Andres Pico (Brigade commander of

the California militia in Southern California), California Adjutant

General Kibbe, and. U.S. General Carlton over and about the arms

"carried off to Texas and the Confederacy" by the Los

Angeles Mounted Rifles. Even Governor Downey would be "dunned"

for the bond which had been posted for arms issued to the Rifles

(the bond never showed up). The small cannon had been left behind

in Los Angeles in the custody of Sanchez and was quickly repossed

by Union authorities. Doubtlessly, the ambulances with the party

were necessary to carry the arms and extra munitions.

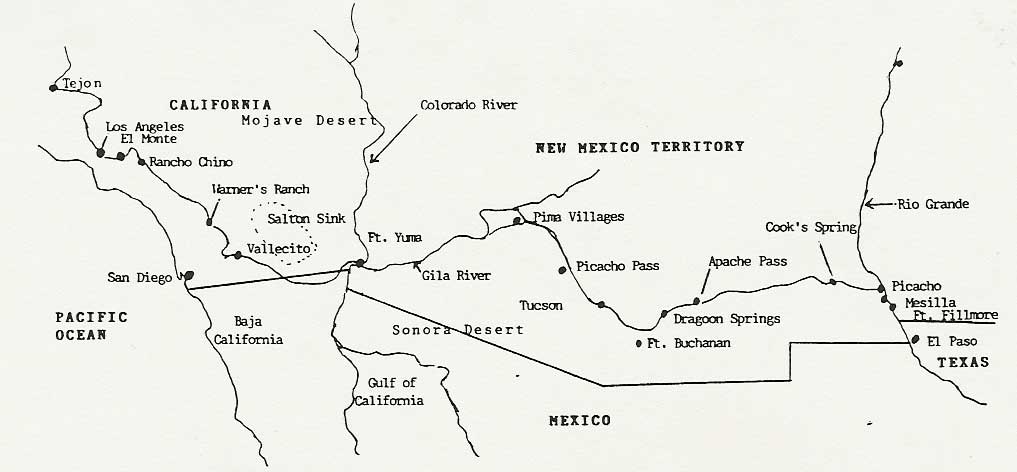

From Warner's, the route would continue to be the Overland Stage

Route. The danger points would be at Yuma

where there was a fort garrisoned by U. S. troops, in the Tucson

area where there were two additional U. S. Army posts nearby,

and at the Rio Grande where Fort Fillmore was strongly garrisoned.

All along the route there would also be the ever present threat

of attack by hostile Indians. The march would be through some

of the hottest and driest regions of the continent where, during

the summer, the temperature could reach 120 degrees. There would

be very little shade and what few breezes there might be only

forced the heat and dryness into the body. The path led over drifting

sands and rocky wastelands. Water sources were limited and often

unreliable. The monotony of the trail, accompanied by their own

trail dust, would add greatly to their fatigue. Though most of

the marches would be by night, there would be little real relief

from either the heat or the dryness.

Captain Ridley led the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles east from Warner's Ranch on the 27th. It took them three days to reach Vallecitos about 35 miles southeast. Here Lewis Armistead and his son joined up and made the party that would cross the deserts complete. There were now a total of 36 in the party. Of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles there were 26 - Captain Ridley, Sergeants Abila and Chandler, and Privates William R. Bower, William Campbell, William H. Cheapline, James D. Darden, John J. Dillard, Carman Frazee, George W. Gift, Cyrus K. Holman, Dillon Jordan, Hugh May, Dave McKenzie, Thomas Morran, L. Parden, Calvin Poer, William N. Robinson, William M. Skinner, Thomas Smith, Thomas Stone house, and Frank Varnell. Of these, about half had not been on the unit's Muster Roll back in March, indicating that recruiting had continued after organization of the Rifles. McKenzie was considered to be the best shot of the entire group after only Ridley himself.

Albert Sidney Johnston and Lewis A. Armistead were the most prominent

of the resigned officers who had joined the Los Angeles Mounted

Rifles for the trip. The others were ex-Lieutenants R. H. Brewer

of the 1st Dragoons; Aaron B. Hardcastle of the 6th Infantry;

Nathaniel Wickliffe of the 9th Infantry; and Francis Mallory,

E. B. Dudley Riley, and Arthur Shaaf of the 4th Infantry. Affiliated

with them were Johnston's servant, Randolph Hughes, and teen-aged

Walker Keith Armistead.

The Rifles left Vallecitos on the night of the 30th traveling

18 miles to Carrizo. The night's journey was highlighted by views

of Thatcher's Comet flaring through the sky. Exhausted, they slept

most of the next day. Then at 3:00 p.m. they set out for Indian

Wells which was 37 long miles away across the Imperial Desert.

The route angled south curving beneath the Salton Sink (now the

Salton Sea) and the sand hills. In a letter to his wife, Johnston

described their stay at Indian Wells:

"Here the water, if clear, is good; but the well had to

be cleaned out, and it was, for us, muddy and unpalatable. At

this place the flies - house flies - swarm in myriads. It was

not possible to throw a veil over your face quick enough to exclude

them. The scrubby mesquite afforded but little shelter from the

burning heat."

Gift later wrote of a "drying, withering breeze" at

this place that made him feel "as one confined in a burning

apartment". From here it was 28 miles to Alamo Mocha and

then 30 more to Cook's Spring (both located in Mexico) and then

northwardly to Yuma, California (At that time, Yuma was within

the boundaries of California. Fort Yuma itself still lies within

the confines of California.)

As they cautiously approached Yuma, they heard the National Salute

being fired (it was the 4th of July) by the guns of the fort.

The temperature there that day was 104 degrees. They camped within

sight of the fort for the next three days to rest and to repair

their ambulances and shoe their horses. How was it that the Los

Angels Mounted Rifles could camp for so long a period within sight

of a stronger garrison of U.S. troops? Especially since orders

had been issued to capture Johnston and any with him? For one

thing, they had found out that all of the officers at Fort Yuma

were sick. This is not surprising as Fort Yuma had, since its

founding in 1850, been described as the worst post in the U.S.

Army due to both heat and pestilence. It was perhaps also that

the officers were exercising some discretion to save their command

- they may have had more to fear from the Rifles than vice versa.

Gift, in later years, related that during their first night there,

their first sentinel, Lewis Armistead, had been approached by

a sergeant and some men from the fort with the proposal that a

goodly number of the garrison would be willing to desert, join

with the Rifles, and then seize and plunder the fort leaving it

a smoking ruin. Apparently most of the Rifles were all in favor

of this course of action. Johnston, when his counsel was sought,

however dissuaded them saying that such would be akin to piracy

since the Company was not yet mustered into Confederate service

and that none of them as yet held Confederate commissions. And

so, California lost its sole chance to have an actual Civil War

battle site.

Southern cartoonist Adalbert J. Volck's 1861 "Albert Sidney Johnston Crossing the Desert" is the only period depiction of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles. Though not particularrly accurate, it did much to romanticize the epic desert crossing.

Leaving Yuma on July 7th, the Rifles proceeded up the valley of the Gila River, across to the Pima villages just south of present-day Phoenix, and then up the Santa Cruz valley to Picacho Pass and on down to Tucson which they reached on July 18th. This portion of their journey was pretty uneventful. The citizens of Tucson made the Rifles quite welcome. Tucsonians had their own grievances against the U. S. government. It had become a part of the United States by the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, yet it was not until 1857 that the government had stationed troops in the area leaving it exposed to depredations of hostile Apache Indians. In March of 1861, citizens of Tucson had held a convention "seceding" as the Arizona Territory. Recently, Federal troops had abandoned Fort Breckinridge northward of the town and enroute to Fort Buchanan had burned the town's only grist mill. About 30 vengeful Tucsonians suggested that they would combine with the Rifles to chase and punish the Federal troops. Johnston again counseled against such an action with the same argument he had used at Yuma. Fortunately, his advice was again followed. Sixty Rifles and Tucsonians would not have had much chance against the two companies of infantry and the two companies of dragoons the U. S. had in the general area. After three days recuperation in Tucson, the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles left on the final, third stage of their journey to the Confederacy. They were here joined by three citizens of Tucson - George Byerson, William A. Elam, and Richard Simpson - the final "enlistees" in the Rifles.

This next stage of the journey would be the most dangerous phase.

Cochise was on the warpath, Fort Buchanan's commander had orders

to intercept them, and Fort Fillmore lay at the terminus. At 8:00

a.m. on July 22nd, they left Tucson with Dragoon Springs, where

the trail to Fort Buchanan intersected, as their goal. It was

essential that they reach this point ahead of Union troops evacuating

the fort lest they be cut off. This made for two days of particularly

hard marching - 30 miles the first day and then 40 miles more

the second day. They had to camp without water on both occassions.

Then, on the 24th, it was 15 miles to Dragoon Springs. Here they

observed a smoke column to the south that indicated Fort Buchanan

had been burned and abandoned with Federal troops on the march.

They had beaten an advance scout of U. S. dragoons by only 36

hours. Their arrival here was later described by Hardcastle: "After

our seventy miles' ride without water, when we reached the wells

entirely spent and dry, we found them foul and noxious with dead

rats." The Rifles cleaned the wells as best they could and

assuaged their thirst.

After only a brief rest, they pushed on to Apache Pass some 40

miles east. Here they found encamped a party of Texas Unionist

headed for California - who were ready to dispute the right to

use of the water. Tired, thirsty and in a bad mood, the Rifles

would not be forestalled. As Gift later wrote, "We had the

force and our necessities were great. We took the water."

Some of the Rifles proposed that the Company remain here and surprise

the evacuating Federal forces in the pass, who - cut off from

water - would be forced to surrender. Again, with his usual argument,

Johnston persuaded them otherwise.

They resumed their march just before noon on July 25th. Over the next two days during their 105-mile march to Cook's Spring, they encountered the burned wrecks of two stagecoaches and the bodies of fourteen who had been killed by the Apache. The Rifles, however, met no hostiles themselves. From Cook's Spring it was but another 60 miles to the Rio Grande

Late on the afternoon of the 27th, the Los

Angeles Mounted Rifles reached the Rio Grande near the village

of Picacho, just seven miles north of Mesilla. Knowing that Fort

Fillmore was well-garrisoned and only eight miles south of Mesilla,

they approached Picacho with caution and stopped two miles short

of the river. They captured a local Mexican who told them that

the brush was full of Texans and that all of the Fort Fillmore

troops had been captured. They did not believe him and after explaining

that they were the advance party for Major Lord's U.S. command,

let him go with a caution to tell nobody of their arrival. The

Mexican went straight to the Texans and told them. About 11:00

p.m., the Rifles moved on into the village and encamped. They

told the villagers the same cover story as being the advance of

Major Lord's command. They again heard that Fort Fillmore had

been captured. Still disbelieving, they put out sentinels to guard

the camp.

Shortly later, Hardcastle and Poer brought in a prisoner called "el Gato Pelado" ("the Skinned Panther" in English). This man had sneaked in to spy upon the camp and on his way out had been tempted to steal Hardcastle's horse only to encounter the shotgun of Cal Poer. "El Gato Pelado" was a Cuban and a member of Captain Coopwood's Spy Company of Col. John Robert Baylor's command of Texans. Enrique D'Hamel (his real name) advised that indeed Fort Fillmore had been captured. Ridley knew Bethel Coopwood who had been Assistant District Attorney in San Bernardino County. He had left California earlier in 1861 and in early July enlisted the San Elizaro Spy Company (said to be composed of mostly Californians) in Texas for Baylor. Ridley instructed D'Hamel to inform Coopwood that Alonzo Ridley and a party of Californians had arrived. Soon thereafter, Coopwood arrived at the Camp and the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles knew that they had safely completed their march of 800 miles. The next day - July 28th, 1861 - the Rifles rode into Mesilla where they were warmly welcomed by John Robert Baylor and his Texas troops. Some of the Rifles began to immediately seek transportation to El Paso and from there to points east.

Only a few days later, on August 1st, Baylor was to proclaim the Confederate Territory of Arizona with himself as its Governor. Needing time to organize its civil affairs, he asked Johnston to take over his command (a battalion of the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles). Johnston was anxious to go east but reluctantly acceded to Baylor's request. He told Ridley that he didn't like the delay "but that it was like being asked to dance by a lady - he could not refuse." Johnston laid plans to capture the U. S. troops from Fort Buchanan but, forewarned, Major Lord diverted them north to Fort Craig and they escaped. After a delay of two weeks, Johnston, Ridley, Hughes and the two Armisteads continued their journey. When they took stage at Mesilla for El Paso, the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles were completely disbanded as a unit. Its members thenceforth served the Confederacy in separate units on many battlefields from Texas to Virginia.

Albert Sidney Johnston of course reached Richmond where his friend Jefferson Davis made him the second-ranking General of the Confederate Army. While commanding all the Confederate forces from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River he was mortally wounded during the first day's action of the Battle of Shiloh. His faithful companion and friend, Randolph Hughes, remained with the Army serving other generals until the end of the war.

Lewis A. Armistead was commissioned Colonel of the 54th Virginia Infantry and soon after promoted to Brigadier General of a Virginia brigade. He died on July 3rd, 1863, of wounds received while leading his brigade during the assault of Pickett's Division at Gettysburg - the "high water mark of the Confederacy." His son Walker K. Armistead became a Sergeant in the 6th Virginia Cavalry and survived the war.

R. H. Brewer formed an early Alabama Cavalry battalion which was later merged with a Mississippi battalion to become the 8th Confederate Cavalry. In 1864, he was killed in action leading a cavalry brigade in the Valley of Virginia.

Aaron Hardcastle, first as Lt. Colonel and later as Colonel, led the 3rd Mississippi Infantry throughout the war.

Francis Mallory became the Colonel of the 55th Virginia Infantry and killed while leading it at Chancellorsville.

Dudley Riley became a major in the Ordnance Department.

Nathaniel Wickliffe the Lt. Colonel of the 5th Mississippi Cavalry.

Arthur Shaaf ended the war as Major commanding the 1st Battalion of Georgia Sharpshooters.

Many of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles who had made the desert journey also be came officers. Captain Alonzo Ridley remained with Johnston as captain of his bodyguard through Shiloh. He then went to Texas and participated in the capture of the U.S.S. HARRIETT LANE in Galveston Harbor. A crack shot, he is said to have slain that ship's commander. Ridley then joined the 3rd Arizona Regiment of Texas Cavalry as a Major. He was captured June 28th, 1863, at Fort Butler, Donaldsville, Louisana, and spent the the remainder of the war as a prisoner of war. After the Civil War, he went to Mexico where he stayed until 1877. He then spent a brief period in Cuba before finally moving to Arizona. He visited friends in the Los Angeles area on a few occassions but never returned to California permanently. He died at Tempe, Arizona, on March 25th, 1909.

Private James Darden became a Captain and a staff officer to Brigadier General Lewis Armistead and later to Brigadier General George H. Steuart.

Private John J. Dillard rose to the rank of Major in the 35th Arkansas Infantry.

Private Cyrus Holman was Sergeant and later Major in the 27th Texas Cavalry.

Private Calvin Poer joined the 8th Texas Field Battery as its blacksmith only to desert in April of 1862.

Private William Campbell is believed to have served in the artillery of Baylor's command.

Private Hugh May perhaps also joined a Texas unit.

The fledgling San Diego lawyer, Private

William D. Robinson, served throughout the war in a Texas unit.

He returned to San Diego after the Civil War and, in 1867, was

elected to the California State Assembly becoming one of the first

ex-Confederates to be elected to a state legislature in a "northern"

state. He died 1878 at Jamul near the Mexican border.

Two privates of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles who made the desert crossing became officers of the Confederate Navy. George W. Gift has been called by the authors of Civil War Naval Chronology "a colorful, unrecognized man of the Confederate Navy, ... a daredevil mastermind." He was commissioned Acting Master in December 1861 and then Lieutenant in March 1862. He served on the New Orleans station, on the C.S.S. ARKANSAS, on the C.S.S. CHATTAHOOCHIE, commanded the blockade runner RANGER, participated in the capture of the U.S.S. UNDERWRITER, and completed the Civil War commanding first the C.S.S. CHATTAHOOCHIE and then the C.S.S. TALLAHASSEE. He returned to California in 1877 settling in the Napa Valley area where he edited newspapers.

Carman Frazee followed Gift into the Navy and in April 1864 was appointed by Gift as Master's Mate on the C.S.S. CHATTAHOOCHIE. At the war's end, he was paroled at Montgomery in his native Alabama.

Advancement of the departure date due to Johnston's joining the party, resulted in 20-30 of the Rifles who had intended to make the trip being left behind. Responsibilities to family and distance kept others behind. 2nd Lieutenant Tomas Sanchez continued as Sheriff of Los Angeles County. Continually under suspicion and watched closely by the Union authorities, he was nevertheless re-elected sheriff in 1863 and 1865. Afterwards he was a rancher but lost most of his fortune in the early 1880's. His home, Casa Adobe de San Rafael, was restored in 1939 and is now operated as a museum by the City of Glendale.

Private Jose Antonio Sanchez, a cousin of the Sheriff, is believed to the the same of that name who became Captain commanding from March through May 1864 of Company D, 1st Battalion of California Native Cavalry,

John Rains and Tom Carlisle, the two rancher-Privates did not long survive. After an arrest party of U. S. troops had visited his rancho in Cucamonga in 1862, Rains tried to avoid its vicinity. While driving his wagon between there and Los Angeles on November 17th, 1862, was stopped by bandits, brutally dragged some distance and then shot once in the chest and twice in the back. Manuel Cerradel who appeared to be his actual murderer was arrested. Sheriff Sanchez endeavored to escort Cerradel to San Quentin but an angry mob seized Cerradel and hanged him on the tug CRICKET in Wilmington harbor. Cerradel had implicated a Jose Ramon Carrillo in the crime but he was soon released for a lack of evidence. Carrillo was himself soon after murdered. Bob Carlisle was greatly displeased over the investigation of the murder of his friend and brother-in-law John Rains and placed the blame on Undersheriff A. J. King. The dispute festered for some months and became known as the King-Carlisle feud. At a ball held in Los Angeles on July 5th, 1863, some partisans of Carlisle attacked King and stabbed him several times - he barely survived his wounds. The next day, King's brothers, Frank and Houston, saw Carlisle inside the saloon of the Bella Union hotel. They drew their pistols, entered the hotel and immediately began shooting at him. Carlisle drew a revolver and shot Frank King who died instantly. Houston King kept up the fight which passed to the sidewalk outside the hotel. Carlisle fell to the sidewalk riddled with bullets. Not yet seriously wounded, Houston King then hit Carlisle on the head, breaking his pistol. With his last efforts, Carlisle moved to the wall, raised his pistol with both hands, and with his last shot felled King. One bystander was wounded and several more had their clothing pierced with stray bullets. Houston King and Bob Carlisle both died the following day.

One of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles later made his way separately to the Confederacy. This was Private Joseph Lancaster Brent. He made his escape by traveling down to San Diego and boarding the Panama steamer ORIZABA. On this ship, he and two fellow passangers - former U.S. Senator William Gwin and former U.S. Attorney Calhoun Benham - were arrested by Brigadier General E. V. Sumner while in Colombian waters. This incident could have involved the United States in a war with Colombia except for the trio's giving consent to the arrest in order to avoid any harm to the citizens of Panama City. They were finally released upon order of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln at Washington. They immediately "went South". Brent became the Ordnance Officer for Magruder on the Virginia Peninsula. He then transferred west as Richard Taylor's Ordnance Officer and gained recognition for organizing and leading the capture of the U.S.S. INDIANOLA on the Red River. He was thereupon promoted to Brigadier General and given command of a Louisana cavalry brigade on April 17th, 1864, becoming the only California citizen to become a Confederate General. Though he retained much property in the state, he never returned to California. He became a power in Louisana politics until retiring to his native Maryland. He died at Baltimore in 1905.

Though their history as a unit was brief, the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles made an impact upon the Civil War. It is doubtful that Albert Sidney Johnston could have escaped California if the Rifles had not already been organized, vigorously led, and ready to take him along with them to the Confederacy. His arrival in the Confederacy boosted morale considerably and held portents for great things until his untimely death at Shiloh. It is perhaps ironic that his fame, while to some extent preserving the memory of the Rifles in crossing the desert, has largely submerged the fact of their existence as a unit, relegating them to brief mention as "Johnston's escort". The impact of their journey was more immediate in California. The success of the Rifles in taking off so prominent a person to the Confederacy shocked Union authorities in California. The State Senate directed a report on all California militia units - and when completed later in 1861, Adjutant General Kibbe's report omitted any mention of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles.

A post, Camp Wright, was established on the Overland Route, first at Warner's and later moved to Oak Grove, to halt groups going east to join the Confederates. Though some individuals and handfull-sized groups did, from time to time, make their way east, no further large parties made it through. Union authorities became even more distrustful of Southern California militia groups and volunteers to the extent that posts in the area were garrisoned by units from northern California. Arms belonging to the State were thereafter much more closely controlled to prevent any others from being diverted to the Confederacy or to the use of Southern sympathizers. The success of the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles had much to do with leading to the failure of later similarly minded groups.

The Los Angeles Mounted Rifles were one of the most unique of all the various companies raised for the Civil War by either side. The facts of their location, their highly diverse ethnic makeup, their incredible journey across the desert at the worst time of the year, their association with so many prominent Confederate generals - all of these would make them stand out. But most unique of all, the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles stand alone as the only Free State militia organization that went Confederate!