The Santa Barbara Presidio

was the last in the line of Spanish defenses that began in North

America on the Atlantic Ocean in Florida with the founding of

the first presidio on the then western front of the new world

at Saint Augustine in 1565, 217 years earlier. The unrelenting

conquest of the new world by the Spanish Empire ended with this

last redoubt at the final western front on the shores of the Pacific

Ocean. As with the San Francisco Presidio, the driving force behind

a presidio at Santa Barbara was Father Junipero Serra. He passed

through the area on foot several times and saw that there were

many Native American villages between Point Conception and the

southern end of the Santa Barbara Channel at present day Ventura.

This region was a big gap in the control of Spain between the

Presidio at Monterey and that at San Diego. The nearest mission

was at San Luis Obispo. Only the Spanish horse mail express ever

passed through this region on a regular basis.

The Spanish were great bureaucrats

and needed a paper trail for everything. Serra started it with

his requests. The Council of War and Royal Treasury approved his

requirements. The King gave Felipe de Neve, who was appointed

Governor of the Californias in October 1774, the task of preparing

a new reglamento. This requirement was transferred from the royal

council to the Viceroy, who gave it to the Commanding General

Croix of the Provincias Internas, who gave it to the new governor,

Neve, in August 1777. Neve based his plans on the earlier Regulations

of 1772, which have been described in an earlier part of this

work. Neve submitted his new Regulations for Governing the Province

of the Californias to Croix in June of 1779. These were approved

by Croix and sent to the new viceroy, Marin de Mayorga, with the

recommendation that the King put them into effect on an interim

basis pending approval. With approval of the King on October 24,

1781, the Neve Regulations became law. These regulations applied

to the presidios of Alta and Baja California, to the Department

of San Blas and to a certain extent to the missions. Included

were provisions for the establishments of three missions - San

Buenaventura, La Purisima and Santa Barbara and a presidio, which

must be located at the center of the Santa Barbara Channel.

In the meantime the Viceroy

directed Neve on April 19, 1776 to move the capital of the Californias

from Loreto to Monterey and to take charge of the affairs of Alta

California. Neve arrived at Monterey from San Diego on February

3, 1777 after passing through the Santa Barbara Channel where

he obtained first hand knowledge of the Native Americans and the

terrain. In a letter of that date to the viceroy, Neve makes the

following statement: "The site which I observed to be most

suitable for establishment of the fort (presidio) is in the vicinity

of Mescaltitlan, the three towns opposite Yslado and in a dominant

and open place. But having to consider the problem of defense

and the availability of cultivatable fields, a special reconnaissance

is necessary in order to find out more about it. Soldiers must

come equipped with weapons and mounted, with two cannon of 4 for

the presidio if Your Excellency approves it's founding.

In this case, the shipment

of clothing and provisions must be sent by ship, and for this

there will have to be a determination as to which of the bays

or harbors of the Channel will be more secure to anchor the ships

and unload their cargo. Without doubt it should be near the site

marked for the fort, concerning which Frigate Lieutenant Diego

Choquet, who anchored in the year 1776 next to the three villages

of the Channel, will be able to advise you."

Neve's first impressions

led him to favor the location around the present day town of Goleta

at the location of the Santa Barbara Airport. This was in Neve's

time a slough with two islands in the middle and several Native

American villages. The name Mescaltitlan was applied to this site

by the Portola Expedition in 1769 because it resembled a similar

slough and island in the Mexican province of Nayarit on the west

coast of Mexico above San Blas, the homeland of many of the early

settlers brought to Alta California by the Spanish. Neve did recommend

further detailed exploration of the area before a final decision.

He referred to a visit by the ship El Principe that was carrying

Father Serra south to San Diego in 1776, which tied up in front

of the Mescaltitlan location. Neve also recommended supplying

any further settlements with supplies brought by ship. A survey

to find the best harbor in the area was recommended.

A letter dated September

3, 1778 from Croix, Commanding General of the Provincias Internas,

to Governor Neve gave official approval for "erection of

a presidio with a garrison composed of a lieutenant, a sergeant,

two corporals and twenty-six soldiers in the center of the Channel

of Santa Barbara, and, under the protection of the presidio, a

mission with the same name and another named San Buenaventura."

The pueblos of San Jose and Los Angeles were also approved.

Once the decision had been

made, plans were formulated to carry them out. As in the expeditions

to found the three earlier presidios, a two-pronged effort was

undertaken to bring supplies by sea and to round up soldiers,

settlers and cattle in Mexico and to move them by land to the

area to be settled. Months of letter writing containing instructions

and plans followed between Governor Neve, the viceroy and General

Croix who was at Arizpe in Sonora, Mexico.

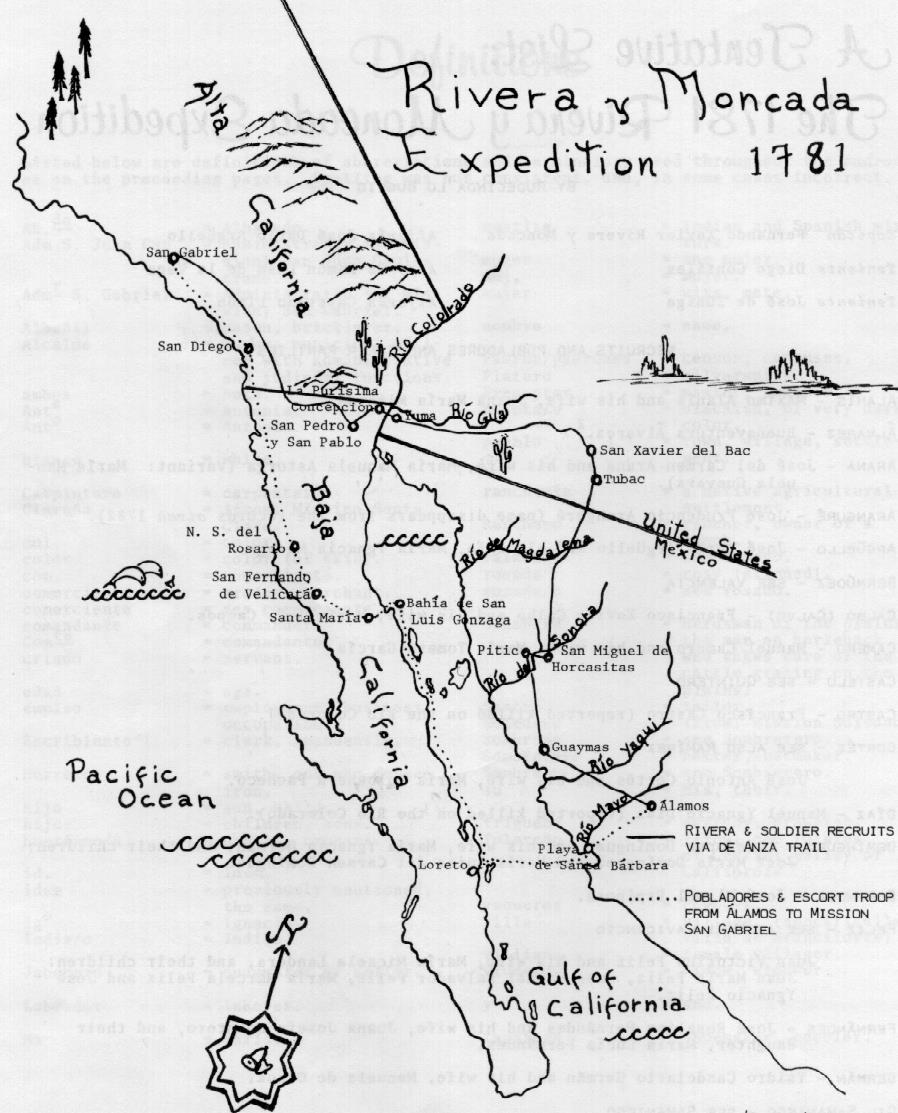

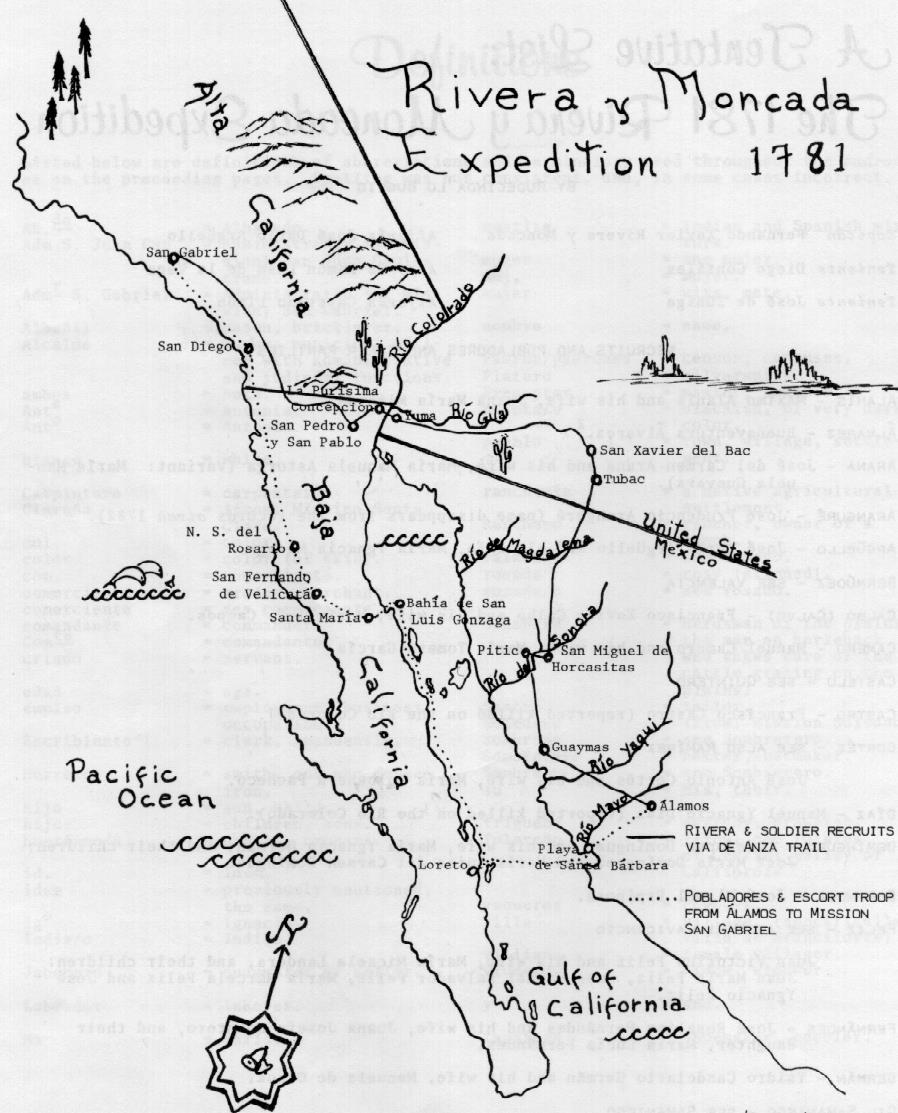

Once again it fell to Captain

Fernando de Rivera y Moncada, Lieutenant Governor of Baja California

at Loreto, to cross over to the mainland from Loreto and recruit

the needed personnel and cattle from primarily Sinaloa and Sonora.

The settlers were to start the pueblos at Los Angeles and San

Jose and the soldiers were to sign up for ten years to man the

new presidio on the Channel. Twenty-four families, thirty-four

soldiers, and over 900 animals were to be moved nearly 1,000 miles

to the north.

The group of 261 settlers

and six soldiers gathered at San Miguel de Horcasitas in Sonora,

north of Hermosillo. The settlers then went south to Alamos for

equipment, clothing, provisions, livestock and pay. Once provisioned,

the settlers split into two groups. The families and cattle heading

for Los Angeles and San Jose went north by way of Tucson and the

Colorado River following the De Anza trail to San Gabriel Mission,

leaving in April 1781 and arriving on July 14,1781. The second

group crossed the Gulf of California by boat from Playa de Santa

Barbara to Loreto and then again by boat north along the coast

to Bahia de San Luis Gonzaga where they landed and then followed

the Portola route up the Baja peninsula to San Diego and San Gabriel.

This group arrived August 18, 1781. The list of names of all involved

was published in Antepasados, Los Californianos, Vol. IV, 1980,

pgs. 59-64.

The first group was accompanied

by Captain Rivera as far as the Colorado River where he remained

behind on the east band to rest the cattle. On July 17, 1781 the

Yuma Native Americans attacked the Spanish settlements on the

east side of the river and massacred the inhabitants. At least

forty-six were killed including Captain Rivera and other members

of the group going north. Thus ended a long and distinguished

career by a devoted Spanish soldier who was one of the founders

of the State of California.

The combined groups camped

at San Gabriel during the winter of 1781 to 1782. During that

time the Pueblo of Los Angeles was founded on September 4,1781

with twelve settlers and their families - forty-six persons in

all. The push further north to San Jose was delayed pending better

weather.

Meanwhile Lieutenant Jose

Francisco Ortega, who was transferred from his post as Commandante

of the San Diego Presidio to the same position at Santa Barbara

by Governor Neve, was training the recruits for the Santa Barbara

Presidio.

We will remember that Ortega

was with the Portola Expedition and is credited by history to

be the first European to see the San Francisco Bay. This same

Ortega was directed by Governor Neve to explore the Channel for

the best location for the new presidio. The spot that he picked

turned out to be the present location of the San Buenaventura

Mission in Ventura. Governor Neve was interested in finding a

location in the middle of the channel and took an active part

in exploring the area.

With improved weather the

expedition of 200 people with horses and mules departed San Gabriel

on March 26, 1782. This group included 60 soldiers with Lieutenant

Ortega at the lead. After three days of marching, the expedition

arrived at the present location of the San Buenaventura Mission.

Father Serra finally achieved his goal of establishing a mission

at the south end of the Santa Barbara Channel. A cross was raised,

a temporary tule chapel was built and on Easter Sunday, March

31, Serra sang the first Mass. With the help of the soldiers and

the local Native Americans a palisade was constructed and water

was diverted from the Ventura River through a newly constructed

aqueduct.

Governor Neve left Sergeant

Pablo Cota in charge of fourteen soldiers to protect the mission

and continue building the new structures. On April 15, 1782 Governor

Neve and the remaining soldiers set out for the trip to Santa

Barbara, a distance of 27 miles. This trek was made in one day.

Upon reaching the present location of the Santa Barbara Presidio,

Neve again conducted a survey of the whole area from Mescaltitlan

to the present location. Paramount to a choice was a place where

a ship could be anchored near enough to unload heavy equipment

and close to the site of the Presidio. Two brass four-pounder

cannon were to be sent to the Presidio by ship when a location

was selected. As in the earlier expeditions, the Royal Navy out

of San Blas, Mexico supported this one. Two ships were sent in

1782 to deliver food and equipment to the presidios.

The Princesa was a frigate

built at San Blas. She was 189 tons, 92 feet long, 24 feet beam,

15 feet Draft. She was armed with six four-pounder and four three-pounder

iron cannon.

The packet Favorita was

purchased by the Spanish Navy from Peru. She was 193 tons, 72

feet long, 25 feet in beam, and 15 feet in draft. No cannon were

reported for this ship.

Before starting this expedition,

the Princesa had just returned from a long and hazardous voyage

to the Philippines. Both ships were well known on the northwest

coast for many years.

Don Esteban Josef Martinez commanded this expedition in support

of the founding of the Santa Barbara Presidio. These ships were

sent to the north in 1782 to supply San Francisco and Monterey.

They were then to sail south to the location of the central coast

and to look for the land portion of the expedition. Pantoja Y.

Arriaga was the second pilot on the Princesa. One of the pilot's

duties was to keep the ship's log. In a voyage such as this he

also conducted surveys and prepared maps of the new area. While

the area had been explored by land, it was not mapped in detail

by sea. The log of the Princesa on this voyage was first translated

by H. R. Wagner and published in 1935 and again by Geraldine Sahyun

and edited and published by Richard Whitehead in The Voyage of

the Princesa in 1982. From this record is obtained a description

of the area of Mescaltitlan Island, as the Princesa and Favorita

were moving south.

"Before reaching

the last point, in the 2nd of the 3 before mentioned, are the

bay, lake, and islands of Mescaltitlan, and on passing at about

a league's distance from it a large opening is to be seen, which

appears to have a large bay in the center and around its circumference

many trees. It is the largest forest to be seen on all this coast

of ravines. Several rancherias were seen in it, having a numerous

Indian population with many canoes."

The two ships continued south while the Princesa fired her cannon to attract the attention of the land party. Hearing the ship in the distance, the land party prepared a signal fire to attract the attention of the sea party. They finally met at the present Santa Barbara roadstead. A flag had been raised at the point to the south of there. This was later named Point Martinez in honor of the commander of the Princesa. At this time Governor Neve had already decided on the location for the presidio at Santa Barbara on April 21, 1782. However, to back up his decision, Neve ordered the ship commander to send the pilot Pantoja Arriaga to Mescaltitlan to conduct a complete survey. The record of this survey is as follows:

The report of this survey is taken from the Whitehead book and

modified as it appeared in Gunpowder and Canvas by the author.

These comments and the resultant maps are the only record of the

original Mescaltitlan area that comes down to us today. The survey

was made on August 12, 1782 when most streams were dry and the

effect of the sandbar was most evident. Had the survey been made

in January the sandbar may not have existed, there would have

been water in the streams and the result may have been different.

However as a result of this pivotal survey, the decision was made

by Neve to go ahead with the selection of the present location

of Santa Barbara. His decision was stated in a letter to Galvez

from General Croix dated August 26, 1782.

Neve picked Santa Barbara

instead of Mescaltitlan because: "besides the advantages

of the land, the grass and lumber, stones, and water, the last

three of which were missing in the second place, the chosen site

at Santa Barbara, is less than a quarter of a league from the

only sheltered place along the coast that is suitable for anchoring

ships." Other considerations were the overlook to the east

that the site in Santa Barbara provided by the high ground above

present Garden Street and the low marshy estero in that direction

which was a barrier to any attack from that direction. At Mescaltitlan

the presidio would have to be located on More Mesa or almost two

miles back from the harbor above present day Hollister Road or

on Mescaltitlan Island itself, which was heavily populated by

Native American villages. At the Santa Barbara location, the only

village was off a mile from the proposed location of the presidio

and considered a safe distance. At the present day Goleta location,

there were five large Chumash villages. The Santa Barbara site

was also out of cannon shot of most shipping. The other consideration,

water, seemed to be better provided by the present Mission Creek

than was the case in the Goleta area in August of that year. So

for all these reasons the fame and importance that has come to

the Santa Barbara location has passed by the Goleta location.

Had dredging been available to the Spanish in 1782, the Goleta

lake and sandbar could have been deepened as is done every year

today at the Santa Barbara harbor and a very impressive city built

at the Goleta location, instead of just the present day airport.

But then that is history!

As in the founding of the

earlier presidios, the first structure was a palisade enclosure.

Governor Neve returned to Monterey leaving Lieutenant Ortega with

forty-one soldiers to begin the work. A location for the permanent

presidio had been determined so the temporary structure was offset

and would not interfere with the future construction site. Work

began on an enclosure of oak palings to enclose an area of 165

feet square with two small bastions. The permanent structure was

to be 220 feet on a side also with two small bastions, but made

of adobe blocks. On June 2, 1782, Neve made an inspection of the

presidio status just five and a half weeks after the founding.

He reported to Commanding General Croix that: "the plastering,

flat roofs, storehouse, guardhouse and barracks remained to be

finished and that the natives were still happy about the Spanish

settlement." In other words, much still had to be done. "The

governor was complimentary of Lieutenent Ortega on most counts,

but said he had to reprimand him for being too familiar with the

troops. He also lacked firmness and determination, and his accounts

as paymaster were in such bad shape, in spite of his intelligence

in such matter, that Neve recommended he be quickly replaced.

He said that if Ortega continued as paymaster the inevitable result

would be bankruptcy. Neve considered him a good officer under

the direction of another commander."

On August 1, 1782 the long

awaited supply ships arrived with the much-needed uniforms, food,

and the two bronze four-pounder cannon. Neve gave Ortega explicit

instructions as to how the supplies were to be handled and inventoried.

In September 1782 Neve was appointed Inspector General of the Internal Provinces and Pedro Fages succeeded him as Governor of the Californias residing at Monterey.

Enlarged section of the Pantoja Map showing the details of the Mescaltitlan area, now the Santa Barbara Airport. Note the numerous Native American rancherias in 1782. From Gunpowder and Canvas by the Author.

By the end of 1782, the

mandatory strength report listed Ortega as commanding officer,

Josef Arguello as his alferez, or ensign, in addition to Sergeants

Pablo Cota and Josef Olivares, Corporals Alejandro de Soto and

Josef de Ortega and fifty soldiers. Fifteen were in the escolta

at San Buenaventura, seven at San Luis Obispo on a temporary assignment

and two were in Los Angeles. This left thirty-two men at Santa

Barbara available for duty, not a large force for the area under

Spanish control.

Water was brought to the

palisade by means of an aqueduct from the Mission Creek. A letter

from Neve to Galvez dated October 20, 1783 states: "The numerous

Indians who inhabit the said Channel remain quiet and tranquil,

and according to the latest news I have received from the said

Ortega, they have gladly and voluntarily labored on the buildings

of the presidio and the aqueduct constructed from the source of

the Pedregozo, distant a quarter of a league, to bring water to

the presidio's very walls facing its principal entrance"

- from Geiger, Life and Times of Serra II, 289-290. The aqueduct

may have ended in a fountain outside the walls and a washbasin,

and perhaps also a reservoir.

Governor Neve's displeasure

with Lieutenant Ortega was displayed when he appointed Don Felipe

Antonio de Goycoechea as Comandante of the Santa Barbara Presidio

on January 14, 1783. His family was centered at Alamos in Sonora,

Mexico. The reader will remember this as the starting place of

the expedition to settle Santa Barbara. Goycoechea joined the

army at thirty-five and moved up in rank quickly. He had good

family connections and extensive experience on the Mexican frontier.

He bore the title "Don" for that reason. His family

was of noble Basque lineage. He commanded the Presidio at Loreto

for a year before being appointed to the comandante of the Santa

Barbara Presidio. He held this post from January 25,1784 to 1802

after which he was Governor of Baja California for eight years.

Ortega was transferred to

Loreto. He applied for retirement in 1786 after 30 years of service

but was denied. He continued in the service until he was retired

as a brevet captain in 1795 but attached to the Santa Barbara

fifty company. He died at his Spanish Land Grant ranch at Refugio

Canyon twenty miles west of Santa Barbara on February 3, 1798.

With the appointment of

Goycoechea, work began in 1785 on the permanent structures of

the Presidio. Construction proceeded along the lines of the Reglamentos

of 1772 using a formula that we have already seen for the earlier

presidios in California. Walls were to be made of adobe with a

chapel, three large warehouses, guardhouse, comandante quarters,

family quarters, soldier's quarters and two bastions. Gardens

separated the quarters from the outer defense walls. One gate

was located facing the ocean as with the other presidios. A smaller

gate was located on the east side. At Santa Barbara the main gate

was on the south side of the quadrangle and the chapel in the

wall on the north side. The comandante's quarters were at the

right of the chapel and the married officers on the left. The

outer walls were about 400 feet on each side. The inner parade

ground was about 300 feet square. There was a casa mata outside

the walls near the east bastion where the supply of about 350

pounds of gunpowder was stored. Two corrals were located on each

side of the entrance behind the walls so that the horses could

be watched by the guards at the entrance. Footings were excavated

and filled with stone as foundations for the adobe blocks in the

walls.

Construction began in 1785

with the construction of thousands of adobe bricks 11"x 22"x

4''. Soldiers, Spanish ship's crews, and the Chumash Native Americans

all took part in the construction and all were paid for the work.

The Chumash were paid one and a half reales per day and five quarts

of corn. Wood beams were first taken from local trees but found

to rot quickly so pine and redwood beams were ordered from Monterey

and sent down by ship. Roof tiles were manufactured at the Presidio.

The south row of buildings nearest the ocean which contained the

warehouses and the main gate was constructed first, followed by

the west side soldiers quarters, the north side with the comandante's

quarters and the chapel, and finally, the east line of buildings.

The outer defense wall was constructed last. Most of the buildings

were completed by 1788, but the outer defense wall took over three

years more to complete. The defense walls were four feet thick

and nine feet high. The final steps were plastering the walls

and whitewash. This went on for several years more.

The Santa Barbara Presidio

construction avoided the mistakes of the earlier presidios, in

that it did not first build a flat roof covered with plaster,

followed by thatch, followed by tile, but built with tile in the

first construction thus saving a huge amount of labor and maintenance.

Most of the buildings had overhanging front porches supported

by poles. A well was located in the inner quadrangle. The work

proceeded briskly because it had the full support and attention

of the Governor and the Viceroy. As buildings were constructed,

the old palisade structure was vacated and torn down. There was

some suggestion that there was a dry moat around the Presidio

but none has been discovered to this time.

A document in the Bancroft Library dated September 16,1788 from Goycoechea to Governor Fages describes in detail the status of construction on the Presidio as of that date. Geraldine Sahyun translated this document in the 1960s. Incorporated in the document is a plan of the Presidio with a number for each building, the length, breadth and height of each room, and the materials of construction for the building or room. The map indicated that it is a statement to Governor Fages, prepared by Goycoechea showing the present state of construction of the Presidio. Bancroft's scribes on tracing cloth, using both sides of the tracing cloth, traced the copy in the Bancroft Library from the original. As a result, the ink has bled through the cloth and the document is difficult to read. The Newberry Library has a similar map of the Presidio with the same date but signed by Governor Fages. The Fages map is also a tracing of the original Goycoechea map. The map itself has been lost to history, but the Fages tracing map was found in the Archivo General de la Nacion in Mexico City. It is much clearer than the Bancroft map and has some measurements added that were omitted in the original Goycoechea map. The Newberry document is "Plan del Real Presidio del Canal de Santa Barbara," by Pedro Fages, September 16, 1788, MS in Map Collection of the Richman Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois. This map appears in its original Spanish form in Citadel On The Channel by Richard S. Whitehead, pg. 116. A clean copy of the Bancroft map also appears on page 191 with an English translation on page 192. Details of the materials and construction of the presidio can also be found in Citadel On The Channel, Chapters 8 and 9.

On August 21, 1790 Goycoechea

submitted a report to Governor Fages listing the names of the

officers, soldiers, and other residents of the Presidio; their

race, age and place of birth; the name, race and age of their

wives; and the names and ages of their children. There are sixty-one

officers and soldiers and six other men listed. With their wives

and children, there were 230 people living in the Presidio.

In October 1794 Goycoechea

ordered that construction expenses should stop and only work on

the chapel and maintenance of the completed buildings would be

allowed.

The first non-Spanish Europeans

visited the newly completed Presidio in November 10-18, 1793.

The English Captain George Vancouver visited Santa Barbara with

his three-ship flotilla, the Discovery, the Chatham,

and the Daedalus. The English were welcomed by Comandante

Goycoechea, who made every effort to supply, feed and entertain

his guests for

the 18-day visit. Vancouver describes his impressions of this

Presidio as he did the others in his journals published in Europe.

He reports seeing two brass nine-pounder cannon at the entrance

to the Presidio. He also observes that the location of the Presidio

and harbor could be made more secure by the placement of a fort

on the hill about a mile away, which was about 150 feet above

it and had a clear field of fire over it. Eventually, a fort was

built at that location.

Vancouver's comments on his impressions of the Santa Barbara Presidio from his journals as presented in Gunpowder and Canvas by the Author, pgs. 2 - 51. We have been told that there were two brass Four-Pounders at the Presidio. Vancouver recommends a fort on the hill on the southwest side of the roadstead.

Vancouver also commented: "The buildings appeared to be regular and well constructed, the walls clean and white, and the roofs of the houses were covered with a bright red tile. The presidio was the nearest to the sea shore, and just showed itself above a grove of small trees, producing with the rest of the buildings a very picturesque effect." Vancouver also stated that the presidio excels all the others in neatness, cleanliness and other smaller though essential comforts and that it is placed on an elevated part of the plain and is raised some feet from the ground by a basement story, which adds much to its pleasantness.

At the time of Vancouver's visit, the Presidio had just been completed

and had not yet seen the wear of the other three presidios visited

by him. Also much better construction techniques and materials

were used in this Presidio since it was the latest and last to

be constructed. The comment about nine-pounder cannon conflicts

with the earlier information that they were four-pounders requested

by Governor Neve. At a later date, eight-pounder cannon were placed

at the fort on the hill. The Presidio was built on a slight hill

with the northeast end being higher than the southeast by about

eight feet. The northeast end did not have a basement. John Sykes,

chief artist with this expedition, rendered the first drawing

of the Presidio and the Mission. It shows the Mission and the

Presidio with the chapel peaking up over the walls, a tower or

torreon on the right side and no bastions. Apparently, the torreon

was added after Goycoechea submitted his 1788 plan since it was

not shown then. The newly completed mission was also visible.

Following Vancouver's visit,

as we have seen in the earlier parts of this work, the Spanish

government became concerned about the threat from foreign powers.

On October 17, 1794 Viceroy Marques de Branciforte began a program

of studies and improved fortifications.

In 1796, work was underway

to enlarge the Presidio chapel from 54 to 99 feet long. The enlarged

chapel was consecrated on December 12th.

In a letter to Governor Borica dated April 10, 1797, Goycoechea

describes the Presidio cannon as "6-caliber", meaning

pounder, or firing a six-pound ball. Still more confusion.

The coast of California was rocked with one of the strongest earthquakes

in California history in December of 1812. Estimated at over 8.5

on the Richter scale, the results were devastating to the Spanish

adobe structures. Almost every building in Alta California was

damaged or destroyed. The Presidio was heavily damaged and never

recovered from this event.

Captain Jose Antonio de la Guerra y Noriega became Comandante

of the Presidio in 1815.

In 1818 the coast of California

was attacked by the Argentine revolutionary, Hipolite Bouchard.

The widespread and steadily growing feeling of hostility throughout

the Maerias for the colonial systems of Europe, which first became

strongly manifest in the American Revolution, was brought with

startling suddenness to the attention of Californios on October

6th. There arrived at Santa Barbara the American brig Clarion,

sailing from the Hawaiian Islands, with the terrifying news that

two ships, the Argentina and the Santa Rosa, were outfitting at

Honolulu for an attack on the California coast. These insurgent

ships flew the flag of the rebel government of Buenos Aires and

they were commanded by Captain Hipolite Bouchard and Lieutenant

Peter Corney respectively. Nearly 400 armed men were in their

crews.

Captain Jose de la Guerra,

immediately upon reception of this news, sent couriers to warn

Governor Sola at Monterey and the missionaries of the more exposed

missions along the coast of the impending attack. When De La Guerra

received the required permission from the Governor, he prepared

to evacuate the women and children of Santa Barbara, along with

those articles of value that could be moved, across the Santa

Ynez Mountains to the safety of the Santa Ynez Mission. Though

Captain Bouchard carried a commission from the Buenos Aires government,

the frightened officials of California branded him and the members

of his crew as pirates. After sacking Monterey on November 22nd,

Bouchard sailed south and appeared off Gaviota on December 2nd.

He landed at Refugio and attacked the Ortega Rancho. The ranch

was sacked and cattle killed but the residents and their valuables

had disappeared into the mountains. The Spanish did manage to

capture three of the insurgents. All of the troops and Native

Americans that could be mustered were gathered to stop Bouchard

without effect. Bouchard debarked and sailed south to Santa Barbara

followed by this large Spanish land contingent at which he fired

several cannon balls without effect. There he sent a man ashore

under a flag of truce to ask for a parley to which Comandante

de la Guerra agreed. In the course of this parley, Bouchard proposed

that, for an exchange of prisoners, he would leave the coast.

De la Guerra agreed and transferred the three prisoners taken

at Refugio and received in exchange a drunken settler whom Bouchard's

men had picked up in Monterey. After the exchange was consummated,

Bouchard continued his voyage south and after a stop at San Juan

Capistrano, was seen no more.

In 1820 the Spanish government

had an unknown artist visit the four Alta California presidios

and prepare a not-to-scale drawing of each showing what features

were there at the time of the drawing. The drawings, held at the

Bancroft Library, have already been discussed for the earlier

presidios in this work. For Santa Barbara, the rear of the chapel

is shown protruding beyond the defensive wall, the chapel bell

tower is indicated on the left front as "Torrecito",

a tower is shown in the east wall near the comandante's quarters

as "torreon de dos cuerpos" or watchtower, the main

gate is shown and two small side gates in the east and west walls.

There are no bastions shown. A defensive wall encloses the buildings.

The main gates are on the inside wall. No water well is shown

although Vancouver refers to one during his 1793 visit. A number

of buildings owned by the Presidio soldiers are shown outside

the Presidio, as is the case at the other presidios at this time.

1822 marked a change in

management of the presidios. The Mexican revolution ended the

Spanish rule of King Ferdinand VII with the government of Mexican

Emperor Agustine Iturbide the First. Everyone in California was

required to pledge allegiance to the Emperor. On April 13, Presidio

Comandante Jose de la Guerra lowered the flag of Spain over Santa

Barbara. As we have seen in earlier sections of this work, this

event marked the beginning of the end of the presidios.

Many of the soldiers of the presidios were assigned to the missions to control the Native Americans and to capture any that attempted to run away. The Santa Barbara Presidio provided its soldiers to six missions: San Fernando, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez and Purisima Concepcion. As we have seen elsewhere in this work, there were many revolts of the Native Americans against the harsh treatment of the soldiers and the Spanish government in general. A revolt broke out at Santa Ynez as a result of an order given by Corporal Manuel Cota of the guard there. As a punishment for a shortcoming that was real or fanciful, one of the soldiers of the guard at Mission Santa Ynez trussed up a Purisima neophyte who was visiting friends at Santa Ynez and flogged him brutally. This mistreatment proved to be the spark necessary for the ignition of the powder keg. A general uprising followed immediately at the three Santa Barbara missions and an attempt was made at San Buenaventura Mission. At Santa Ynez, the Native Americans attacked the soldiers, who defended themselves behind the thick walls of the mission building. No lives were lost in this attack, but in the fighting inflammable material within the building was set on fire and a part of the structure was burned. This happened on a Sunday February 22, 1824. The next day the news of the conflict having been carried to the Presidio in Santa Barbara, a military force under the command of Sergeant Carrillo arrived on the scene and prepared to give battle to the insurrectionists. The Native Americans gave up the fight and fled to the Purisima Mission. Here the Native Americans took possession of the buildings. Corporal Tapia with the four soldiers stationed there barricaded themselves in their quarters along with the members of their families and the two missionaries and fought off the Native Americans until their supply of powder gave out. During this fight four whites and seven Native Americans were killed. The whites surrendered but were released by the Native Americans and sent to Santa Ynez. Then the Native Americans prepared to defend themselves against the attack that they knew would be launched against them.

In Santa Barbara the Native Americans tried to disarm the soldiers

at the mission, but when they resisted, a fight ensued and the

soldiers were badly beaten. Outraged by this depredation, Captain

de la Guerra led a large force to the mission. In the battle that

followed, two of the Native Americans were killed and three others

wounded. Four of the soldiers were wounded. With no results the

troops withdrew to the Presidio. The Native Americans then broke

into the storerooms and took what provisions they could carry

and retreated up Mission Canyon with their families. De la Guerra

and his soldiers again attacked the mission but found the Native

Americans gone. The soldiers sacked the Native American village

and captured some women and took them off to the Presidio. Later

four old Native Americans from Dos Pueblos encountered a band

of soldiers who killed them.

The main body of the Native

Americans escaped to Tulare Lake in the Central Valley. In April

1824, Captain de la Guerra dispatched Lieutenant Narcisco Fabrigat

and his Mazatlan soldiers, originally rushed to Alta California

in 1818 during the Bouchard attack on coastal ports, to bring

the truant Native Americans back from the Valley. Eighty picked

soldiers engaged the Native Americans at San Emigdio where two

encounters took place in which four Native Americans were killed

and a number of men on each side were wounded. The fugitives took

advantage of a dust storm and escaped. In June Governor Arguello

offered the Native Americans at Tulare a full pardon and the Mission

Padre Ripoll, whom they trusted, induced them to return to the

Santa Barbara Mission.

In the meantime, Governor

Arguello sent a large force from Monterey to Purisima to reduce

the rebels there. After a short fight, the rebels asked their

Padre Rodriguez to intercede for them and to arrange surrender.

This was done. There was supposed to be a pardon as with the Santa

Barbara rebels. However as an aftermath of this conflict, seven

Native Americans were shot as murderers, four were sentenced to

ten years of hard labor at the Presidio, and then to permanent

banishment, and eight others were condemned to the Presidio for

eight years. The padres were outraged by the severity of this

punishment but the governor would not relent and thought stricter

punishment was deserved.

This whole event showed

a complete lack of consideration by the Spanish for the plight

of the Native Americans and was the last nail in this peoples'

coffin leading to their ultimate extinction. Alta California was

a province of Mexico after the revolution. Governor Echeandia

called an assembly of electors in San Diego in February 1827.

This assembly chose Comandante Jose de la Guerra of Santa Barbara

to represent them for a two-year term in the congress organized

in Mexico City. De la Guerra was Spanish-born and not allowed

to serve under the new laws of Mexico which prohibited Spanish

under 60 from living in Mexico unless married to a Mexican-born

wife. He elected to go anyway. After a difficult journey to Mexico

and a harrowing escape, Captain de la Guerra returned to Santa

Barbara where he found Mexican-born Don Romualdo Pacheco in the

position of Comandante. De la Guerra then retired at Santa Barbara

to manage his large land holdings and to finish work on his grand

adobe casa which still stands today on De la Guerra street. Captain

de la Guerra was allowed to stay in California as a result of

his fame and position in state affairs and a pardon from Governor

Echeandia. In later years he again became the comandante.

The French explorer, A. Duhaut-Cilly visited Santa Barbara on August 29, 1827. His ship Le Heros was of 362 tons with a crew of 32 men and 72 guns. He also published his comments about the Presidio in his journals, as did Vancouver. His brief comments follow:

Duhaut-Cilly traveled the

California Coast for about a year, stopping at Santa Barbara on

several occasions. He left California in August 1827 and returned

to France via Hawaii and Canton, China.

The above quote tells us

that Captain de la Guerra was in the process of building his adobe

casa in 1827, that he purchased beams for it from Monterey, and

that he was appointed to represent the province in Mexico City.

He mentions a bastion on the Southeast corner of the Presidio,

which was not shown in the 1820 drawing. This is the first reference

to the existence of this structure. There had been doubt that

it ever existed. But he states that it is of poor quality. He

refers to a balcony at the comandante's quarters which must be

the tower mentioned in the 1820 drawing. However, he places the

comandante's quarters at the northwest corner of the Presidio

while it was on the right side of the chapel or the northeast

corner. The tower was also located on the 1820 drawing at this

corner.

Due to the poor conditions

that existed at the four presidios after California became a province

of Mexico, the soldiers complained for years of lack of pay and

provisions. At Monterey, a political agitator named Joaquin Solis

from Chile had recently come to Monterey with a contingent of

ragtag soldiers and convicts sent by the Mexican government. He

was a fiery orator and talked the soldiers at the Monterey Presidio

into a revolt against the Mexican government. On November 12,

1829 he seized control of the Monterey Presidio. He then left

a contingent of his own followers in charge and took 100 men to

San Francisco where he convinced the Presidio there to surrender

and join the cause. Again, leaving a few loyal supporters in charge,

Solis proceeded south to Santa Barbara to take control of the

Presidio there. A group of Americans at Monterey formed an opposition

party to Solis and sent a courier to warn Governor Echeandia at

San Diego of the approaching army of about 200 men. Echeandia

arrived there after two weeks and took command of the Santa Barbara

Presidio. He sent a courier to Solis promising amnesty to any

rebel who would desert. Solis crossed Refugio Pass and made camp

in Refugio Canyon, where he sent a return message to Echeandia

demanding surrender and stating he would in turn grant amnesty.

The Governor ordered all residents of the town to the Presidio,

except for thirty old women whom he sent to the Scottish ship

Funchal anchored in the harbor. On December 13, 1829 the Presidio

army of 90 headed by Comandante Pacheco encountered the Solis

army near Cieniguitas, present day Modoc and Hollister streets.

Pacheco beat a hasty retreat to the Presidio. Solis marched to

within a mile of the Presidio in the vicinity of Mission and De

La Vina streets where he set up cannon and opened fire on the

Presidio. The governor returned the cannon fire. For three days

cannon balls were lobbed back and forth without hitting anything.

Solis then ran out of gunpowder and provisions. The Solis army

returned to Monterey where it was captured by the American army

loyal to the government. Joaquin Solis was eventually deported

to his native Chile. As historian H. H. Bancroft phrased it, "the

battle of Santa Barbara" was the first in which Californian

was pitted against Californian."

Alfred Robinson was an early visitor and settler in California. After years of business and a long life in California, he published Life in California in which appear the second earliest known drawings of Santa Barbara entitled "Presidio (or Town) of Santa Barbara, Nueva California. From a Hill Near the Castillo, Founded April 21, 1782", dated 1829. He draws the Presidio without walls. Just to the left of the Mexican flag appears to be the tower (torreon) of the Presidio mentioned in the 1820 drawing. The de la Guerra adobe is to the left with its second story, Altito; and Burton's Mound is in the foreground. The mission is shown with two towers.

The Santa Barbara Presidio fell into disuse after becoming part

of Mexico for the same reasons presented earlier in this work

as did the three other presidios. The transition from the presidio

to the pueblo resulted in the construction of private homes around

the original structure and the sell-off of parts of the Presidio

for that purpose so that with time the Presidio disappeared into

the pueblo. The chapel was abandoned for the new parish church

in 1854. The walls slowly dissolved and parts of the decaying

structures of the Presidio were salvaged for building materials

for new adobes.

In 1841 the French government sent their Mexican attaché, Duflot de Mofras, to California to learn as much as possible about the Mexican settlements there since it had been 14 years since Duhaut-Cilly's visit. Unlike the former visitor, de Mofras did not have a formally outfitted expedition. He moved from place to place on ships of convenience. He first arrived from San Blas on the ship Ninfa in May 1841. He stayed in areas for months to observe the culture and study the economic conditions. He described his findings in a two-volume book that was published in France in 1844 entitled Duflot De Mofras' Travels on the Pacific Coast by Marguerite Eyer Wilbur, Ed, and trans. 1937. The De Mofras comments reveal that the Presidio is deteriorating but still staffed by a garrison of 15 soldiers and 5 officers. There are one four-pounder (iron) and two bronze eight-pounders cannon. The hide and tallow trade is well established since hide sheds have been erected near the shore. The "Spanish battery" is now razed. This reference verifies that the battery did exist. A drawing in De Mofra's books shows the location and chevron shape of the "battery".

In 1844, the "Kings Orphan" visited Santa Barbara and

prepared two pencil sketches of the pueblo. The tower in the 1820

drawing is shown, however no walls or bastions are visible. The

intact bell tower in front of the chapel is clearly visible. A

flagpole with flag is shown in one view. The de la Guerra adobe

is shown on the left view along with the two-story Alpheus B.Thompson

adobe. The Mission is shown in the background with two towers.

In one view, a building is shown on Burton's Mound in the foreground

along with a beachside "hide house" to the right.

U.S. Naval Lieutenant James Alden with the U.S. Coast Survey drew the next view of the Presidio in 1855. He visited the Presidio and drew the chapel showing the ruined bell tower, an intact but deserted chapel and the melted defense walls and some of the collapsed buildings on either side of the chapel. A triangular buttress to prevent collapse supported the back of the chapel.

The chapel bells are shown

mounted on a rack in front of the ruins of the bell tower. The

chapel was abandoned after 1855 when the new parochial Our Lady

of Sorrows Church replaced it as the place of worship in Santa

Barbara. The original drawing of the chapel is located at the

Santa Barbara Mission Archives Library.

Edward Vischer visited all the missions and presidios in 1865

and prepared drawings of the missions and some of the presidio

remaining buildings. One of his pictures of Santa Barbara shows

the one remaining building that housed the soldiers' family, called

El Cuartel. To the left of this drawing and just underneath the

eave is an image of a three-masted sailing ship in the roadstead.

Other ships appear on the right side in the background.

Henry Chapman Ford made

a drawing of the Casa de la Guerra on the backside in 1886 presenting

the complete view of the "Altito" or second story supposedly

built by Captain de la Guerra to house his gold. This structure

has since been removed but it is seen in early

photographs of the Casa.

In 1895 Walter A. Hawley

of Santa Barbara became interested in the history of the Presidio

and the Mission. He retained a civil engineer and had the remains

of the Presidio surveyed and a map prepared drawn with pencil

on heavy brown paper. The map is located in the files of the Santa

Barbara Mission Archives Library. As a result of his historical

research on Santa Barbara, Hawley published a book in 1910 entitled

Early Days of Santa Barbara. The book was republished in 1920

by Mrs. Hawley and again in 1987 by John C. Woodward with additional

illustrations. The history of the Presidio, Mission and ranchos

as well as many other historical events were presented. At the

time of this publication in 1910, El Cuartel, the comandante's

quarters and the Canedo Adobe were the only parts of the Presidio

still standing. The Canedo Adobe is at the far left of the chapel

location. It was once used to house Presidio soldiers and their

families. The adobe was later granted to Jose Maria Canedo, a

Presidio soldier and extensively remodeled in the 1940's by Elmer

Whitaker.

The earthquake of 1825 severely

damaged the comandante's quarters. The building could not be repaired

and was torn down.

By 1911 the chapel no longer existed. The Chinese settled in and around the old Presidio compound. On the old chapel site the Chinese constructed a two-story Buddhist Temple. This structure lasted until 1967 when it was torn down to begin the Presidio reconstruction.

Underneath the site were found the brick-lined vaults of Spanish

and Mexican Presidio residents buried in the chapel.

The Santa Barbara Presidio

is the only one of the five Spanish presidios that has been partially

restored. Primarily the north side, which includes the chapel,

has been restored. Part of the comandancia and the torreon in

the east line of buildings has also been restored.

The Santa Barbara Trust

for Historic Preservation, a non-profit organization, was formed

in 1963 with restoration of the Presidio as its primary objective.

The trust then acquired, restored and donated El Cuartel to the

State. Later El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park

was formed. El Cuartel is the oldest building owned by the State

of California. Several other properties in the Presidio area have

been acquired for the project, including the Canedo Adobe and

the site of the Presidio Chapel. The Trust operates the State

Park under an agreement with the State Department of Parks and

Recreation.

Archeological investigations

within the Presidio's quadrangle have been conducted since the

mid-1960s. A large portion of the fort's stone foundations has

been located. Extensive and ongoing research in original Presidio

documentation has provided much information about the Presidio's

history. As a result of these investigations, the Trust has been

able to reconstruct the padre's quarters, the chapel, comandancia,

and torreon with the assistance of the California Conservation

Corps and volunteers working under professional supervision.

Excavations have also located

the aqueduct from the reservoir at Mission Creek near the Mission

that entered the Presidio at the rear of the comandancia. To date,

the casa mata has not been found. Some think it is located on

the Rochin property at 820 Santa Barbara Street. No cannon from

the presidio period have been recovered. Cannon were movable and

either found a new home on some ship, were buried or sold for

scrap.

While State, County and

City revenues have been provided for land acquisition in the Presidio

quadrangle, the planning and financing of reconstruction have

been largely the Trust's responsibility.

Many of the local place

names and family surnames of Santa Barbara are due to the first

settlers of the Presidio and to the Comandantes and Governors.

Most of the pioneers were from the western provinces of Mexico,

only a few were from Spain. In the following list the Comandantes

of the Presidio are reviewed.

The officers of the Presidio

were civil as well as military and consisted of the comandante,

who had sometimes the rank of lieutenant but generally that of

captain; and the habilitado, who had charge of all branches of

the revenue and was generally postmaster. The duties of habilitado

were frequently discharged by the comandante.

The first comandante was

Captain Jose Francisco Ortega, born in Guanajuato, Mexico. He

was engaged in mining in early life but moved to Baja California

where he entered the military service. He served as Comandante

at Santa Barbara and Monterey and continued to perform military

service until shortly before his death. He supervised the construction

of the temporary palisade presidio and constructed the first water

supply for the presidio and farm plots.

In 1784 Ortega was succeeded

in command by Captain Felipe de Goycoechea, who was the Comandante

at Santa Barbara until 1802. During his term of office the permanent

Presidio was constructed and most of the mission buildings were

finished.

A rendering of the Presidio based on the 1788 Comandante Goycoechea Plan, drawn by Russell A Ruiz and on display in the Museum of the Comandanica in the northeast corner of the restored Presidio. Photograph by the Author, 2001.

After leaving this assignment, he was made Governor of Baja California.

Goycoechea was succeeded by Lieutenant Raimundo Carrillo, who

for five years was Comandante at the Presidio and discharged the

duties of his office with firmness yet clemency.

This period was memorable

because of the earthquake of 1806, which damaged not only some

of the buildings of the Mission but also the Presidio Chapel.

The walls of the latter were badly cracked and a severe gale almost

completely destroyed the edifice. Carrillo was born in 1749 at

Loreto, the capital of Baja California; and came to Alta California

about twenty years later, becoming a soldier. He served as a corporal

at Monterey and later as a sergeant at Santa Barbara. He was made

lieutenant and Comandante at Monterey and two years later was

Comandante at Santa Barbara.

Captain Jose Dario Arguello,

who for nine years was Comandante at Santa Barbara, succeeded

Carrillo in command. Captain Arguello was born in Queretaro, Mexico

in 1755 and when twenty years old enlisted in the army. One of

the most important acts of his administration was the opening

of common schools but unfortunately they received little public

support. During this time the disastrous earthquake of 1812 occurred

in December causing great damage to many of the buildings at the

Mission and elsewhere in California. Extensive damage to the Presidio

resulted from this event. Some considered reconstructing the Presidio

on another site. For a short time Arguello was acting governor

of Alta California and served for several years as Governor of

Baja California. Arguello was one of the most influential men

in California where he resided for thirty-four years.

Arguello was succeeded in 1815 by Captain Jose Antonio de la Guerra y Noriega whose command extended over 24 years. He was born in Spain in 1779 of a distinguished family and while still very young moved to Mexico to live with his uncle. He entered the army as a cadet and occupied several military positions until 1806 when he was promoted to Lieutenant of the Santa Barbara Presidio. In 1810 he was chosen Habilitado General of both Californias and sent to Mexico but was arrested by Mexicans during the revolution and returned to Santa Barbara. In 1815 he was appointed Comandante which office he occupied with a few interruptions until 1842. He was promoted to Captain soon after his appointment to Comandante. During his long life Captain de la Guerra exercised a strong influence in the political affairs of Alta California. He died in 1858 and was buried at the Mission.

Gumesindo Flores, a Mexican brevet lieutenant colonel who was

Comandante at Monterey from 1839 to 1842, succeeded De La Guerra.

Flores was actively engaged in territorial affairs during his

short term as Comandante at Santa Barbara and is regarded as the

last Comandante, although Raimundo Carrillo was acting commander

during his absence for part of the year of 1846. In December of

1846 Captain Fremont crossed the Santa Ynez Mountains with his

American battalion and occupied Santa Barbara during the conquest

of California.

References

The following documents were used for references and excerpted

to prepare the foregoing history of the Santa Barbara Presidio:

The Narrative of James O. Pattie by James O. Pattie; The History

of California by H.H. Bancroft; Early Days of Santa Barbara by

Walter A. Hawley; Exploration of the Coast of Southern California

in 1782 by Henry R. Wagner, Quarterly Publication of the Historical

Society of Southern California, pgs. 135-138; California Pictorials

by Jeanne Van Nostrand and Edith M. Coulter; Fabricas by Elisabeth

L. Egenhoff; A Brief Story of Santa Barbara by Edward Selden Spaulding;

Old Spanish Santa Barbara by Walker A. Tompkins; Royal Presidio

of Santa Barbara Archaeology of the Chapel Site by Brian Fagan;

The 1781 Rivera y Moncada Expedition by Rudecinda Lo Buglio, Anteposados

Volume IV 1980-1981, pgs.59-64; The Voyage of the Frigate Princesa

to Southern California in 1782 by Richard S. Whitehead; Gunpowder

and Canvas by Justin M. Ruhge; Felipe de Goycoechea: Santa Barbara

Presidio Comandante by Jarrell C. Jackman; Citadel on the Channel

by Richard S. Whitehead; California Missions Studies Association

WWW.Ca-Missions.Org

|

|

|

|

| 1781 | Jose Francisco de Ortega | September 8, 1781 to January 25, 1784 |

| 1784 | Felipe Goycoechea | January 25, 1784 to August 31, 1802, Appointed on January 17, 1783 in Loreto |

| 1802 | Jose Raimundo Carrillo | 1802 to 1807 |

| 1807 | Jose Arguello | January 1, 1807 to October 13, 1815 |

| 1815 | Jose de la Guerra y Noriega | October 13, 1815 to January 1, 1828, Suspended part of 1828 to 1830 |

| 1819 | Gabriel Moraga | December, 1819 to April, 1821 (Acting only) |

| 1828 | Romuldo Pacheco | December, 1828 to November, 1829 and April to August 1830 (Acting only) |

| 1828 | Romuldo Pacheco | April to August 1830 (Acting only) |

| 1830 | Jose de la Guerra y Noriega | November 1, 1830 to November 2, 1832 |

| 1833 | Juan M. Ibarra | July 1833 to April 1836 |

| 1837 | Jose Castro | December 25, 1837 to March 1838 |

| 1838 | Jose Ma. Villa | April 1838 (Acting only) |

| 1839 | Jose de la Guerra y Noriega | January to December, 1839 |

| 1840 | Jose de la Guerra y Noriega | June and July, 1840 to October, 1841 |

| 1841 | Gumesindo Flores | November, 1841 to March, 1844 |

| 1845 | Jose Carrillo | September 3, 1845 |

| 1846 | Gumesindo Flores | Again appointed January 26, 1846 |

| 1847 | Henry S. Burton | May 26, 1847 |

| 1847 | Francis J. Lippitt | July, 1847 to September 8, 1848 |

| 1848 | Captain Smith | September 8, 1848 |

Source: Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation

Source: Santa

Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation