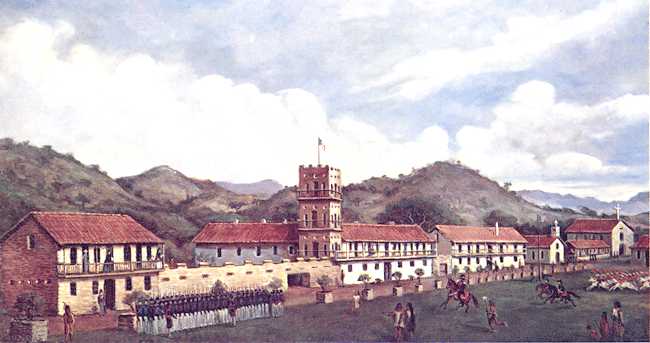

Drawing of the San Francisco Presidio by Acting Comandante Hermenegildo Sal. See below for explanation. BANC MSS C-A 6 pg. 234

The establishment of another

presidio north of the Monterey area was not in the original plans

of the Spanish Monarch. Spain had no knowledge of the large body

of water to the north. Vizcaino era maps did refer to a river

at the location of the Golden Gate but it was not explored and

the location was passed by. That all changed on July 14, 1769.

After establishing a precarious hold in San Diego, Portola took

a small party north in search of Monterey. An advanced party under

Sergeant Jose Ortega, a criollo born in Guanajuato in central

Mexico who would be destined to serve at the garrisons of San

Diego, Monterey, and Santa Barbara during his career, reported

that they had seen a "brazon del mar" - an arm of the

sea. The Spanish explorers noted this chance sighting. In 1770

Don Pedro Fages took it upon himself to forage a land route to

the north. Fages and a handful of lancers, along with some muleteers,

rode to the Santa Clara Valley. From there they went east, encamping

near the present city of Alameda. By November 28th, the men viewed

a large "bocana" or estuary mouth. Not being able to

cross the Punta de los Reyes, Fages halted and then made his way

back to Monterey. In March of 1772 Fages again returned north

with six soldiers, a muleteer, a Native American servant and the

Majorcan-born Fray Juan Crespi to gain a clearer understanding

of the large body of water to the north. From the east bay they

saw the Farallons and three islets within the bay that someday

would be known as Alcatraz, Angel Island and Yerba Buena. Armed

with this added intelligence, Fages's party concluded its journey

with a report and chart that prompted additional interest in the

region.

Having read these reports,

Father Junipero Serra began to lobby the viceroy for two more

missions in the vicinity of what came to be called the Port of

San Francisco, one in the Santa Clara Valley and one at the opening

to the bay. Don Pedro Fages felt that he did not have enough soldiers

to support another missionary program. However, Viceroy Antonio

Bucarelli y Ursua championed Serra's cause, relieving Fages and

replacing him with Capitan Fernando Xavier de Rivera y Moncada

as military comandante of Alta California. Fages was sent off

to the Apache wars in Arizona.

Charged with another survey

of the "Port and River of San Francisco", Rivera commanded

16 lancers, a muleteer, two servants and one priest, another native

of Majorca, Fray Francisco Palou. The 21 riders left Monterey

on November 23, 1774. By December 4th, they halted at "a

long lake ending down at the shore" (now Lake Merced in the

southwestern part of San Francisco). Rivera continued on with

Palou and four troopers until they reached either what now is

called Land's End or perhaps present-day Point Lobos, where they

set up a cross. The next day they headed home making their way

to Monterey by December 13th.

The result of this exploration

was a plan and program to settle the area south of the Golden

Gate with a presidio and a mission. This was the northernmost

area of the Spanish possessions over which they could exercise

any control. The Spanish had no ships stationed in the area with

which to go further north and provide any meaningful control across

the Bay.

To facilitate his plans,

Viceroy Bucareli turned to Captain Juan Agustin Bautista de Anza

of the Tubac Presidio, in present day Arizona, to found the presidio

and provide the Christianized Mexican Native American settlers

for the missions. His effort to do so has already been discussed

in detail in the earlier introductory portion of the "presidio"

section of this volume.

In the meantime, 30-year-old

Juan Manuel de Ayala played another role in preparing the way

for Spanish settlement in northern California. As the skipper

of the packet San Carlos, Ayala sailed from San Blas with supplies

for the proposed colony. His other duties included the charting

of the bay and its shoreline, and ascertaining whether a navigable

passage existed to the inland waterway from the sea. Finally,

Ayala sought to learn whether a port could be established there.

On August 4, 1775 the San Carlos arrived just outside the present

day Golden Gate. The next morning, Ayala sent his first pilot,

Jose de Canizares, into the harbor with a longboat. That evening

he followed, anchoring somewhere near what became North Beach.

This was the first European ship to enter this great bay. During

the next 44 days Ayala and Canizares completed a thorough reconnaissance

before heading back to Monterey on September 18th. Shortly thereafter,

Ayala enthusiastically reported the fine harbor presented "a

beautiful fitness, and it has no lack of good drinking water and

plenty of firewood and ballast." He also concluded that it

possessed a healthful climate and "docile natives lived there".

A chart of the Bay of San Francisco was prepared by Jose de Canizares.

The de Anza party of 240

settlers and 1,000 head of domestic stock reached Monterey on

March 10, 1776. On March 23rd, Anza left his weary fellow sojourners

at this location and took an advanced party from Monterey to select

the new outpost of the empire.

According to an account

kept by Fray Pedro Font, on March 27th, "the weather was

fair and clear, a favor which God granted us during all these

days, and especially today, in order that we might see the harbor

which we were going to explore." After a march of four hours,

they "halted on the banks of a lake or spring of very fine

water near the mouth of the port of San Francisco," today's

Mountain Lake. This spot afforded a resting place for the tired

riders. Then, Anza took Font, another officer, and four soldiers

to scout further. Going to the northernmost tip of San Francisco

Bay's peninsula and looking down from White Cliffs, Anza had seen

enough. He ordered the party back to camp. There, Font set down

his somewhat over-optimistic impressions: "This place and

its vicinity has abundant pasturage, plenty of firewood, and fine

water, all good advantage for establishing here the presidio or

fort which is planned. It lacks only timber, for there is not

a tree on all those hills, though the oaks and other trees along

the road are not very far away. Here and near the lake there are

"yerba buena" and so many lilies that I almost had them

inside my tent." Font continued and, for one of the first

times, clearly used the term San Francisco as the name of the

great bay: "The port of San Francisco.is a marvel of nature,

and might well be called a harbor of harbors, because of its great

capacity, and of several small bays which it unfolds in its margins

or beach and in its islands."

On March 28th, Anza returned

to the Cantil Blanco (White Cliffs) of the previous day to erect

a wooden cross. This was at or near the present day toll plaza

on the south side of the Golden Gate Bridge. This action marked

the formal act of possession for Spain. Anza also selected the

ground where the cross stood as the spot for a presidio to protect

the region. Then the party further surveyed the immediate area.

Fray Font recorded: "On leaving we ascended a small hill

and then entered upon a mesa that was very green and flower-covered,

and an abundance of wild violets. The mesa is very open, of considerable

extent, and level, sloping a little toward the harbor. It must

be about half a league wide and somewhat longer, getting narrower

until it ends right at the white cliff. This mesa affords a most

delightful view, for from it one sees a large part of the port

and its islands, as far as the other side, the mouth of the harbor,

and of the sea all that the sight can take in as far as beyond

the farallones. Indeed, although in my travels I saw very good

sites and beautiful in all the world, for it has the best advantages

for founding in it a most beautiful city, with all the conveniences

desired, by land as well as sea, with that harbor so remarkable

and so spacious, in which may be established shipyards, docks,

and anything that might be wished. This mesa the commander selected

as the site of the new settlement and fort which were to be established

on this harbor: for, being on a height, it is so commanding that

with muskets it can defend the entrance to the mouth of the harbor,

while a gunshot away it has water to supply the people, namely,

the spring or lake where we halted. The only lack is timber for

large buildings, although for huts and barracks and for the stockade

of the presidio there are plenty of trees in the groves."

Neither Font nor Anza, however,

would have to wrestle with the actual establishment of a settlement

since both men left the bay area for Monterey on April 5th, arriving

there some three days later. By April 14th the two men departed,

once again this time setting out for Mexico, where Anza would

receive another promotion and a new assignment destined to take

him away forever from California.

Father Font was another

of the gifted Franciscans to chronicle early California history,

but only for a short period because he was there in connection

with the second Anza expedition. Born in Gerona, Catalonia, he

came to Mexico in 1763. Within a decade, he moved to Sonora as

a missionary among the Pimas. Upon his return with Anza in 1776,

he went to Ures. There the priest completed the short version

of the diary that gained him fame, the longer edition being completed

in 1777. Three years later, Father Font died at Caborca. Font

included a map of the Port of San Francisco in his diary.

Thus it fell to Anza's second-in-command,

Jose Joaquin Moraga, to lead the final leg of the colonizing expedition

northward. Setting out from Monterey on June 17, 1776, some 193

settlers (both soldiers and civilian, some with families and other

single adventurers) made ready for a new life. By June 27th, this

contingent under Moraga arrived in the Bay Area and halted at

the site of what became the Mission Dolores. There the group rested

and waited for supplies which the San Carlos carried. The next

several weeks passed with Moraga actively exploring the region.

On these forays he concluded that a plain to the southeast of

the Cantil Blanco seemed more advantageous for a military outpost.

Indeed, Moraga realized cold fogs often shrouded this windy spot

favored by Anza. Consequently, he may have desired a slightly

milder climate than the exposed cliffs selected by Anza. Certainly

he sought convenient sources of water, which he found on "a

good plain in sight of the harbor and entrance, and also of its

interior. As soon as he saw this location the lieutenant decided

that it was suitable for settlement." With this in mind,

Moraga relocated the main force to the spot he selected. On July

26th Moraga's main force arrived at a clearing overlooking the

bay and immediately began work on a chapel and some crude shelters

for the garrison.

Moraga served both as comandante

and habilitado of the Presidio of San Francisco from its founding

until his death on July 13, 1785. The son of Jose Moraga and Maria

Gaona, he hailed from Mission Los Santos Angeles de Guevavi, in

today's Arizona, and was born on August 22, 1745.

In the early stages the

main priority was to survive while awaiting sea borne supplies.

During this time Moraga's force remained in its rudimentary encampment

without any special military preparations. That situation changed

when the San Carlos finally arrived on August 17th. After the

ship's captain, its pilot and the ship's chaplain came ashore,

they concurred with Moraga's selection for the fort and presidio.

With this, the pilot Canizares laid out: "A square measuring

ninety-two varas (ninety yards square each way) with divisions

for church, royal offices, warehouses, guardhouses and houses

for soldier settlers, a map of the plan being formed and drawn

by the first pilot." To expedite construction a squad of

sailors and two carpenters joined in to complete a warehouse,

the comandancia and a chapel while the soldiers worked on their

own dwellings. On September 17, 1776 with sufficient progress

being made, the San Carlos crew joined the soldiers and citizens

and four missionary priests at a solemn high mass. The ceremony

of formal dedication was followed by the singing of the Te Deum

Laudamus accompanied by the peal of bells and repeated salvos

of cannon, muskets and guns. The roar and sound of the bells doubtless

terrified the heathens, who did not allow themselves to be seen

for many days.

The Royal Regulations of

1772 required that the presidios be constructed of adobe brick.

This was a suitable material and design for presidios on the Southern

Spanish Provincias Internas but it was never suitable for the

northern climate of Monterey or San Francisco with their high

winds and heavy rains. The Moroccan design was meant for the arid

climate but the Spanish bureaucracy could not adjust to geography.

Wooden or stone buildings were more appropriate for those climates.

However the Spanish soldiers followed orders and planned a design

with an adobe wall and bastions that followed the 1772 regulations.

Consequently, from the beginning the San Francisco Presidio was

subject to continual rebuilding. The Presidio was dependent on

the supply ships from San Blas for basic food needs and there

were often food shortages.

In mid-June of 1778 the

ship Santiago arrived after a 3½ -month voyage from San

Blas but did little to reduce the shortages of food. In fact,

the demands increased by the 1777 order to found the pueblo on

the Rio de Guadalupe. Work at the Presidio was delayed so Moraga

could spend much of his time in the autumn of that year establishing

the civilian settlement. Five settlers with their families and

nine soldiers with some knowledge of farming left San Francisco

in November 1777 for the site of the new town to the south. The

governor selected San Jose de Guadalupe from Loreto as the name

for the settlement. The Hispanic male population in the San Francisco

district increased by almost a third during the year due to those

associated with the presidio and missions; however only two new

soldiers joined Lieutenant Moraga's military force.

Circumstances continued

to undermine efforts toward improvements in the first years. When

the new governor of both Californias, Felipe de Neve made an inspection

in April 1777, he noted that while Moraga began work on enclosing

the quadrangle with a wall, the completed comandante's quarters

and warehouse, both of adobe, appeared to be very substantial,

a finding which tended to indicate that Moraga's 1776 plan reflected

what he had hoped to construct rather than what had been built.

Neve found all other structures to be "mere huts." Consequently,

the governor ordered future construction to be of adobe built

atop stone foundations. Unfortunately, this prescription came

too late. During the winter of 1778-1779, the Presidio suffered

heavy damage from the weather. Severe storms, especially in January

and February, destroyed a major part of the palisade walls, the

warehouse and a casa mata, this last-named structure possibly

standing outside the quadrangle near the entrance to protect the

gate. By 1780, none of the buildings erected in 1778 and little

of the walls stood, having been toppled by the intense rains and

strong winds.

Neve, born in Baylen, Kingdom

of Andalusia in 1728, became the first Governor of both Baja and

Alta California to reside in Monterey, which then became the capital

when he relocated there on February 3, 1777. A lieutenant colonel

when he first came to Monterey, Neve received his promotion to

colonel on January 5, 1778. On September 10, 1782 he terminated

his governorship in California and assumed the position of Comandante-Inspector

of the Provincias Internas. By August 12, 1783, he rose to Comandante

General of this same jurisdiction, having gained his brigadier

generalcy earlier that year. Neve died on August 21, 1784 at Hacienda

de Nuestra Senora de Carmen de Penablanca, Nueva Vizcaya.

Further damage to the Presidio

occurred on October 11, 1779. In September 1778 the Spanish ships

Princesa and Favorita, under the command of Lieutenants Igancio

Arteaga and Juan Francisco de la Bodega Y Quadra, arrived at San

Francisco on a return trip from explorations to the northwest

coast. They laid over for about six weeks while the men recuperated

from scurvy. During this respite at the Presidio a fire destroyed

the hospital tent used by the two crews and gutted one of the

houses.

Another problem, which undermined

the morale and discipline on the Spanish frontier, was due to

Spanish white supremacy and social inequality. Any enlisted man

who could show an official certificate attesting to his pure white

ancestry (criollos or peninsulares) could be granted the status

of a soldado distinguido and assume the honorific title of "don"

along with enjoying certain other privileges, which included the

right to wear swords such as those carried by officers, exclusion

from menial labor, and extra considerations for promotions. At

San Francisco usually only sons of officers qualified for this

distinction since regularly the enlisted men were mestizo, mulatto,

or of other mixed blood. This represented one example of the class

distinctions based on European or colonial heritage which grew

up in Spanish California and throughout Spain's New World holdings.

In the end this discrimination was one factor that led to the

Mexican revolution of 1810 and 1822.

The decade of the 1780s saw few improvements to the buildings

at the Presidio of San Francisco. In a few cases the soldiers

had to build palisade huts for their families when their adobe

houses did not stand up well in unfavorable weather. By this time,

one account indicated that the Comandante lived in an adobe while

four walls of varying heights from 2.5 yards to 4 yards surrounded

the compound, which also enclosed a stone facility and palisade

with earth structures that served as stores, the church and habitations

of the garrison. This undistinguished record resulted from a lack

of timber and tules near the post, poor quality adobe and a shortage

of skilled workmen among the 15 to 20 soldiers, who with their

families, regularly made up the garrison during the late 1770s

and early 1780s.

In 1782 Moraga was promoted

to the rank of Lieutenant. The crown also approved $1,200 expenditure

for the Presidio of San Francisco's construction some six years

after the fact. As this amount had been spent long before, the

troops and servants would be reimbursed for their labors. In many

instances big and small, the home government moved at a snail's

pace.

The chapel was completed

in 1784 but a gale blew down one corner of the presidial square.

Moraga's effort to build a guardhouse during the same year came

to a similar end when the strong winds of October destroyed the

partially completed structure because the men wanted for proper

materials to tie down the roof and brace the walls.

Moraga toiled as the first

Comandante of the San Francisco Presidio until his death on July

13, 1785. On that day, the command passed to Lieutenant Diego

Gonzalez, who reported from Monterey, while the alferez of the

company, Ramon Lasso de la Vega, became the new habilitado. Both

men experienced considerable trouble during their assignments

at San Francisco. Before coming to his new post, Gonzalez had

been arrested once for a variety of minor offenses. At San Francisco

he continued his irregular conduct despite reprimands and warnings

from the governor. Finally Nicolas Soler, the Adjutant-Inspector,

ordered Gonzalez's confinement. After two or three months under

house arrest, Gonzalez went to Sonora.

Alferez Ramon Lasso de la

Vega succeeded Gonzalez, followed by Alferez Hermenegildo Sal.

Jose Dario Arguello followed him, after an equally negative rating

as the previous two comandantes.

Jose Arquello was born in

1753 in Queretero, Mexico. He became a soldier of the Regiment

of Dragoons of Mexico on September 20, 1772, serving in expeditions

against the Apaches and helping to found settlements along the

Colorado River. On July 14, 1781 Alferez Arguello arrived in San

Gabriel. He assisted in the founding of pueblos in Los Angeles

and San Buenaventura. On February 9, 1787 he gained promotion

to lieutenant and eventually reached captain on December 1, 1806.

In California he first served at the Presidio of Santa Barbara,

being posted there even before the fort's construction. Arguello

remained at Santa Barbara as Alferez until his promotion to lieutenant

took him to San Francisco as comandante. His tenure lasted until

1806 when, as a captain, he left and took command of Santa Barbara

from 1807 through 1815. From July 24, 1814 through August 30,

1815, he served as Governor ad Interim of Alta California and

then became Governor of Baja California from 1815 through 1822.

He retired in 1822 in Guadalajara where he died sometime between

1827 and 1829.

Besides their duties at

the Presidio a small detachment of escoltas was stationed at each

of the missions where they protected the missions and missionaries.

The soldiers assisted in overseeing the neophytes at their daily

chores and kept guard even during church services. The corporal

sometimes served as the mission's majordomo and took charge of

criminal justice, punishing minor offenses, making investigations

and sending periodic reports and suspects for more serious matters

to the Presidio. At the mission, soldiers lived in a common barracks

arrangement if single, and in small quarters if married. Bachelors

gave their rations to the spouses of their married comrades. The

wives prepared the meals as well as assisted with other domestic

chores. The same circumstances existed at the Presidio of San

Francisco.

If not sent to the mission,

soldiers carried on numerous other tasks. A noncommissioned officer

(comisionado) provided a similar function for the Pueblo of San

Jose to that of the corporals overseeing the mission escoltas.

Other men carried messages, dispatches and the mail, much as pony

express riders would in a later U.S. era. Some guarded officials

as they traveled in the district or looked after prisoners assigned

to public works. Sentry duty, usually given out as a punitive

measure to those who had committed some minor infraction, was

a regular requirement with an average stint being three hours

at a time. Exploration parties and expeditions against the local

Native Americans took up considerable energies, too.

When not occupied in strictly

martial pursuits, the men watched over the growing herds of livestock

at the Rancho Del Rey where their vaquero functions extended to

roundups, branding, castrating bulls, and slaughtering. Each presidio

maintained a Rancho Del Rey to provide fresh meat to the troops

and their families. Each presidio had its own brand for the cattle.

Likewise, they maintained plots for vegetables, as well as worked

at various other food production-related tasks. They gathered

wood and performed different jobs to help maintain their families.

Those with skills of carpenters, smiths, tailors, shoemakers and

potters found ample extra work, as these craftspeople were in

short supply in California. Individuals without specialized trades

might hire on as common laborers, although much of this type of

work went to prisoners or Native Americans who performed either

for pay or as unpaid captives. Moreover, if a soldado distinguido

had to do fatigue duty, he supposedly received an additional bonus

of ten reales in advance. At a later date when some men refused

to do such manual labor because Arguello did not have the funds

to pay them, the comandante placed the strikers in the stocks,

evidently they did not remain there for very long, especially

since one of those who led the "no pay, no work" faction

was Arguello's young brother-in-law.

With many problems, the grand vision for the Presidio waned as the decade of the 1780s came to an end. Its defects as a barren site with harsh climate and remote location from the rest of New Spain weighed heavily against the garrison's success. In fact, the adjutant-inspector of California even advocated the abandonment of the site but this suggestion went unheeded. The need for an outpost to protect the northernmost missions and the strategic position of San Francisco Bay made it impossible to entertain the withdrawal of the troops. Yet, after more than a dozen years of precarious existence, San Francisco stood as an impotent sign of defense rather than a bastion of empire. Subsequent events would espouse the sham in the not-too-distant future.

In March 1791 Lieutenant

Jose Arguello relocated to Monterey. Hermenegildo Sal and Jose

Perez Fernandez managed the affairs of the Presidio through to

1796. Ex-governor Fages made a visit to the Presidio during the

spring of 1791 while the supply ship Aranzazu arrived during the

summer. On September 25th Sal led a party to Santa Cruz to dedicate

the new mission there.

In his March 4,1792 report

to Governor Jose Antonio Romeu, Sal includes a drawing of the

presidio describing the "as built" structures at that

time. Sal describes the on-going work and the continued futility

of building with mud and adobe in the northern climate. What is

built one day is washed away the next. On December 29,1792 Sal

wrote to the new Governor at Monterey Arrillaga, "The labor

spent on the Presidio is incredible and yet there are now but

slightly more or less buildings than at first."

In 1792 the Presidio had

just one three-pounder brass cannon. Sal felt that he needed 10-12

cannon to defend the harbor from foreign attack. The Spanish had

supplied California with twenty-three bronze cannon, large and

small, as part of the stores brought with Portola.

On November 14, 1792 Captain

George Vancouver arrived at Yerba Buena Cove in the ship H.M.S.

Discovery. Sal used his lone cannon to welcome them with two salutes

from the same gun. Vancouver was warmly received by the Spanish

and given food, wood and water. Vancouver's visit was part of

a world tour, which included surveying the Spanish holdings in

California and to assessing their strengths. Vancouver's comments

about the San Francisco Presidio which he visited on November

17 appeared in his report to the Admiralty on his return to England

as follows: "We soon arrived at the Presidio, which was not

more than a mile from our landing place. Its wall, which fronted

the harbor, was visible from the ships, but instead of the city

or town, whose lights we had so anxiously looked for on the night

of arrival, surrounded by hills on every side, excepting that

which fronted the port. The only object of human industry, which

presented itself, was a square area, whose sides were about two

hundred yards in length, enclosed by a mud wall, and resembling

a pound for cattle. Above this wall, the thatched roofs of their

low small houses just made their appearance. On entering the Presidio

we found one of its sides still unenclosed by the wall, and very

indifferently fenced in by a few bushes here and there, fastened

to stakes in the ground. The unfinished state of this part afforded

us an opportunity of seeing the strength of the wall, and the

manner in which it was constructed. It is about fourteen feet

high, and five feet in breadth, and was first formed by uprights

and horizontal rafters on large timber, between which dried sods

and moistened earth were pressed as close and as hard as possible,

after which the whole was cased with earth made into a sort of

mud plaster, which gave it the appearance of durability, and of

being sufficiently strong to protect them, with the assistance

of their firearms, against all the force which the natives of

the country might be able to collect." Vancouver correctly

states that the Presidio is adequate to defend against the "natives

of the country" but would not withstand an assault from a

European force, for which it was never intended.

Vancouver's party inspected

the inside of the Presidio and then made a three-day journey to

Missions Delores and Santa Clara, from November 20th to 23rd.

Vancouver's party was the first foreign power to penetrate into

the Spanish hinterlands in California. The British expedition

departed on November 26, 1792 for Monterey. The Governor ad interim,

Jose Arrillaga reprimanded Sal for allowing the British such freedom

to inspect the Spanish possessions.

Jose Joaquin de Arrillaga

came from Aya, in the Basque Province of Guipuzcoa, where he was

born in 1750. A bachelor, he came to Nueva Espana as a member

of the Volunteer Company of the Presidio of San Miguel de Horcasitas

in Sonora, serving there from May 25, 1777 through March 30, 1778

when his promotion to alferez brought a transfer to duty in Texas.

He continued to rise in rank. As a captain, he transferred to

the Presidio of Loreto in Baja to assume dual assignments as commander

of that post and as lieutenant governor of the Californias, assignments

he held from 1783 through 1792. On April 9th of that year he assumed

the position as Governor ad Interim of the Californias and remained

in this capacity until May 14, 1794 when Diego de Borica replaced

him. Again, between January 16,1800 and March 26, 1804 he fulfilled

this same duty. In between time, he continued as lieutenant governor

and commander at Loreto. He became a lieutenant colonel on December

15, 1794 and a colonel sometime in 1809. Arrillaga died at Mission

Nuestra Senora de la Soledad, Alta California on July 24,1814.

As a result of the English

visit and despite the censure from Arrillaga, Comandante Sal received

long overdue support to strengthen the presidial district. The

viceroy had selected a fortification at the site originally chosen

by Anza in 1776. By 1793, a temporary earthwork with six mounted

guns had appeared on this site. This structure was to be replaced

by a more permanent work consisting of 10-foot thick embrasures

on the seaward side of adobe faced with brick and mortar. Behind

this stood an esplanade on which the heavy guns with their four-wheeled

siege-type carriages rested. The esplanade, made of heavy timbers,

had a plank flooring about 20 feet wide, held together by nine-inch

spikes. On the land side, the walls of unfaced adobe stood only

five feet thick. There lighter guns on two-wheeled carriages sat

on the ground.

Superintendent of construction

for the Department of San Blas, Francisco Gomez, provided his

expertise. Master gunner Don Jose Garaicochea directed the placement

of the cannon. These men and three sawyers had come up from Mexico

aboard Aranzazu originally bound for Bodega Bay before being reassigned

to the Castillo. Antonio Santos also arrived with the ship and

took charge of the manufacture of tile and burnt brick. The master

worked with Christian Native Americans provided by the missions

and non-converted native people brought up from the area around

Santa Clara. Woodchoppers went into the hills west of San Mateo

for timber, going a distance of more than 10 leagues to secure

the redwood. It took about a week to bring back the lumber (weather

permitting) while 23 yoke of oxen hauled the material northward.

Additionally, the laborers made many bricks and tiles before the

rains halted work in January 1794. In early March 1794 when the

rains ceased, efforts resumed and continued throughout the year.

With all the heavy masonry and timberwork completed and after

an expenditure of 6,400 pesos 4 reales and 7 granos, the new Castillo

de San Joaquin was dedicated on December 8, 1794.

As mentioned earlier, one

of the duties of the Presidio was to provide protection for the

missions from the Native Americans. However, that was easier said

than done. In 1795, the number of troops stationed in the presidia

district was Lieutenant Jose Arguello, one sergeant, four corporals

and 31 soldiers scattered over this large area. With these figures,

little wonder that in September 1795, 280 neophyte men and women

felt confident enough to run off from Mission Dolores. Their numbers

included several who had lived at the place for a long time. Troops

could do little to respond, and lacking a sufficient force to

pursue these runaways, recapture proved all but impossible. Native

Americans living at Mission Santa Clara also tried to escape but

efforts were made to retrieve them. The captives faced whippings

and a month of labor at the Presidio, probably wearing shackles

for the duration of their punishment.

On June 27, 1795 the new Governor Diego de Borica visited San

Francisco and recommended that a new presidio be built at the

present site of Fort Winfield Scott and the old location abandoned.

No action was taken.

Borica was a Basque who came from Bizcaya. He became a cadet in

the Infantry Regiment of Seville at 21. He served in this unit

from March 15, 1763 through July 31, 1764 when his appointment

as a lieutenant of Infantry Regiment of America brought him to

New Spain. For a decade he served in Mexico until a transfer to

the cavalry in 1774 brought him to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Thereafter,

he performed a number of duties, eventually earning the rank of

lieutenant colonel on February 5, 1785 and only 12 days later

became a colonel. Borica came to California as governor, a post

he held from May 14, 1795 through January 6, 1800. He returned

to New Spain on a leave of absence because of ill health and died

in Durango on July 19, 1800.

Spring of 1796 saw the arrival

of the special infantry unit from Spain called the Catalonian

Volunteers. Most of the unit of 75 men arrived aboard the Valdes

and San Carlos with their leader, Lieutenant-Colonel Pedro de

Alberni. The catalyst for this activity was the beginning of the

war between Spain and France that began with the rise of republicanism

and Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Volunteers were to support

the leather-jacketed soldiers in their efforts to control the

Native Americans, help settle the land and assist in the construction

of new coastal batteries to protect New Spain from possible attack

from France, England or Russia.

Alberni was born about 1745

in Tortosa, Catalonia. His military life began in 1757 while he

was but 12. By 1762, he served as a cadet in the Second Light

Infantry Regiment of Catalonia. Over the next five years he rose

to second sergeant and first sergeant. With that rank, he volunteered

for service in the New World, where he went in 1767 as a sub-lieutenant

in "the newly organized Company of Catalonian Volunteers."

After a stint in Sonora on campaigns from 1771 to 1781, Albrni

served in the garrison at Guadalajara in Jalisco and Mesa del

Tonati in Nayarit. In 1782, Alberni assumed command of the Volunteers.

At that point his rather ordinary career transformed into a more

important one. After eight years as captain of the company, he

and his 80 men received orders for Nootka where they were to guard

Spanish vessels and reestablish fortifications. Alberni received

the title of comandante of arms and governor of the fort. Alberni's

two years in the Northwest demonstrated his many abilities. He

returned to New Spain where he attended to his family and soldierly

duties until 1795. In that year war with France stimulated action

on Spain's part to send reinforcements to California. In 1796,

Alberni headed some 75 men and became the commander at the San

Francisco presidial district. As a lieutenant colonel in the Spanish

army he was the highest-ranking man in the Californias. He remained

in the Bay Area until 1800 when he relocated to Monterey as comandante.

Alberni died there on March 11, 1802 from dropsy, leaving all

his estate to his widow.

New quarters were erected

along the east side of the Presidio walls for the Catalonians.

Along with Alberni the viceroy sent the military engineer from

the Royal Corps of Engineers, Alberto Cordoba. Cordoba spent two

years helping to improve the fortifications in Alta California.

He recommended rebuilding the Presidio in San Francisco on another

location and assisted with the founding of the Villa Branciforte,

a fortified pueblo at Santa Cruz. With his help the San Francisco

Castillo de San Joaquin was improved and fortified but Cordoba

felt that the location and construction were useless for defense

of the entrance to the Golden Gate. Cordoba recommended a counter

battery across the Golden Gate and another battery further along

the bay.

Spain and France settled

their differences but fighting between Spain and England resumed

in late winter 1797.

The second San Carlos, alias

El Filipino was lost in a storm in the Bay on March 23, 1797.

The ship broke up on the shore. The three new cannon for the Castillo

were off-loaded and left on the shore before this mishap. The

original San Carlos used in the Portola Expedition had been lost

at sea two years earlier.

In May 1797 the supply vessels,

Concepcion and Princesa arrived and contributed to local defenses

by using their sailors to help rebuild the Presidio and the Castillo.

These sailors received two extra reales a day as additional pay.

The counter battery recommended

by Cordoba was not built but the Bateria de San Jose at Yerba

Buena composed of five small guns of no use at the Castillo were

placed in a small enclosure of eight embrasures between April

and June 1797.

In the spring of 1800, Alberni

took several of his infantrymen and their families to Monterey.

Their relocation left the outpost with a token force of 13-foot

soldiers, five gunners and no soldados de cuera at the San Francisco

Presidio. The post reverted to a semi-caretaker status and a hardship

assignment.

In 1799 the Americans began

to arrive. The first "Boston Men' sailed into port aboard

the armed merchant ship Eliza. In 1803 the Alexander followed

by the Hazard arrived at San Francisco. The latter carried 22

cannon and 20 swivel guns with a crew of 50 to man them. The Spanish

had no more than eight men in the garrison. In addition the remaining

Catalonian Volunteers were ordered back to Mexico.

Native Americans continued

to revolt and to be arrested by the escolta and made to work on

the Presidio or Castillo. On March 10, 1806 Luis Arguello became

comandante of the Presidio. Don Jose Arguello transferred to Santa

Barbara.

During the winter of 1805-1806,

members of the Russian settlement at Sitka suffered near starvation

and scurvy. The imperial inspector visiting the colony at the

time, Chamberlain Nikolai Patriotic Rezanov, resolved to sail

to California to get food for his men. The Russian ship Juno

arrived at San Francisco on March 28,1806 with a load of merchandise

to be used in trade for food supplies for its scurvy-ridden crew

and the colonies to the north. The Russians were instructed to

anchor in front of the Presidio. The Russians and Spanish could

not understand each other's language but found Latin to be a common

language that both could understand. The ship's doctor and naturalist,

G.H. von Langsdorff, was not impressed with the Presidio. He described

it as having "the appearance of a German farmstead rather

than a fort." The first known rendering of the Presidio was

prepared by Langsdorff and published in the journals of the voyage.

Alfrez Arguello informed

Rezanov that he was forbidden to trade with the Russians. However,

he had notified the governor and arrangements might be worked

out to provide needed supplies. In the meantime the Presidio presented

the ill crew of the Juno with cattle, sheep, onions, garlic,

cabbages and several other sorts of vegetables and bread to combat

the effects of poor nutrition. The fresh food restored them to

good health and gave an indication of the potential bounty of

the area for agriculture.

After ten days passed, Governor

Arrillaga made his way to San Francisco with an entourage that

included Lieutenant Jose Arguello. When Arrillaga arrived, a salute

from the guns of the fort and the battery greeted him, the booms

from the cannon hidden further within the harbor surprising the

Russians since the Yerba Buena battery could not be seen from

the anchorage. Later, the Russians managed to have a closer look

at this emplacement. Renzanov made the following comments in his

report: "Weak as the Spanish defenses are, they have nevertheless

increased their artillery since Vancouver's visit. We later secretly

inspected the battery (Yerba Buena). It has five brass cannons

of twelve-pound caliber. I heard that there are several guns in

the fortress (the Castillo). As I have never been there

and in order to disarm suspicion did not allow others to go either,

I do not know if there are more or less guns there."

Further surveys by the Russians

indicated that the north shore of the Bay offered some excellent

positions for forts that could control the entrance without any

danger of retaliation from the Spanish battery as the proposed

sites for Russian defenses rose higher than those of the Spanish

on the south side of the harbor and also was out of range. The

Russians could not help but notice that a ship could slip past

the Castillo's guns by hugging the out-of-range northern shore

as it entered port. In the meantime talks continued with Governor

Arrillaga to arrange a mutual trade agreement. At the time the

viceroy opposed commerce with foreigners.

Rezanov became romantically

involved with Donna Conception Arguello and requested permission

of marriage. This event led to one of California's memorable love

stories. A marriage contract was drawn up but no marriage could

be performed until Rome authorized the union because Rezanov was

not a Catholic. As a result of this arrangement, Governor Arrillaga

agreed to permit trading with the Russians. As the world now knows,

Rezanov was killed in a horse riding accident in Russia while

on his way to obtain the Czar's permission to marry Donna Concepcion.

The bride never heard of these events until late in life. She

had spent her single life waiting for Rezanov to return.

The Juno's crew filled

the ship's hold with provisions. They made ready to sail in the

third week of May, leaving 11,174 rubles (an estimated $24,000)

worth of goods in exchange for 2,000 bushels of grain, five tons

of flour and other edibles. As the Russian ship sailed out of

San Francisco Bay, she exchanged cannon salutes with the Spaniards

at the entrance to the harbor. The Russians' last glimpse of the

Spanish settlement was the large group on the high white cliff

- Governor Arrillaga, the whole Arguello family and many others

all waving goodbye with hats and handkerchiefs.

In 1809, the Russian-American

Company began fur-collecting activities from an initial base at

Bodega Bay. Local soldiers arrested Alaskan Indians caught chasing

sea otters and fur seals in the Bay. Likewise deserters from the

Russian base appeared in the presidial district. The Spanish promptly

took them into custody.

During the French invasion

of Spain, the soldiers in California, like Spanish Americans generally,

remained loyal to the imprisoned Spanish royal family. To assure

continued support however, the authorities required the men to

take an oath of allegiance to Ferdinand VII.

With the mother country

under Napoleon, political unrest heightened in Central and South

America. The effects made their way to San Francisco. In 1810,

insurgents on the high seas captured supplies and equipment destined

for California. From this date until the end of the Spanish period

in California, the soldiers never again saw their pay. The semiannual

supply ships, called memorias, rarely made the trip to California,

dictating that the presidios had to rely on foodstuffs from the

missions.

All during the early part

of the year 1811, many Russian-directed Native Americans appeared

around the bay. Mission Native Americans sent out to report on

the interlopers' activities spied 130 canoes in the vicinity of

the harbor's entrance, all hunting fur seals. The Russian supply

ships for the fur-collecting expedition anchored in Bodega Bay.

Some time during July the intruders left the area and were not

seen again until the following year.

In mid-1812 Arguello sent

Gabriel Moraga with four men to explore the area for intruders.

He discovered a Russian brigantine about 8 leagues north of Bodega.

It carried 80 men from Unalaska and Kamchatka to the California

site where Russians had already begun to construct a small fort

(destined to become Fort Ross) some 150 yards square with cannon

mounted behind the walls. In spite of the armament, Moraga noted

the Russians treated the Spanish soldiers in a friendly manner.

Gabriel Moraga was only

about 10 when the native of Santa Rosa del la Fronteras went with

his father, Josef Joaquin Moraga to start a new life in California

as part of Anza's Second Expedition. He joined the San Francisco

Company as a private in 1783 when his father still commanded there.

During his military career he rose through the ranks to sergeant

and by 1806 obtained his commission as an alfrez. He would become

a brevet lieutenant in 1811 and a lieutenant some six years later.

By 1820 he boasted a 37-year record as a soldier and had served

in 46 expeditions against Native Americans in the San Francisco,

Monterey and Santa Barbara presidial districts where he served.

In 1813, Lieutenant Moraga

again made his way to Fort Ross for exchange of views on occupation

and to deliver 20 cattle and three horses. The Russians wanted

to trade for food supplies in exchange for items needed by the

Spanish due to the lack of supplies from San Blas.

During 1814 two British

ships visited the port of San Francisco. The war between Spain

and Britain was now at an end. One of the ships was the armed

merchantman Isaac Todd and the other was the man-of-war Raccoon.

The captain of the 28-gun Raccoon requested and received permission

to repair his vessel at San Francisco, the ship having been damaged

during the War of 1812 in an attack and capture of the American

trading post at Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River. Eventually

the ship would be repaired in Marin County on the beach across

from Angel Island, thereby giving its name to the body of water

now known as Raccoon Straits. The 130 crewmen of the British naval

vessel spent a month in the Bay Area. After buying provisions

and a thousand pounds of gunpowder, Raccoon set sail for the Sandwich

Islands on its mission to destroy American shipping.

In 1814, Lieutenant Moraga

visited Fort Ross, after which he prepared a short report describing

the fort. He observed that forty gente de razon and many Kodiak

Native Americans lived there. A number of cannon guarded the place.

The house built for the comandante and his pilot boasted a most

remarkable luxury for the remote area - it had glass windows.

On this journey to Fort

Ross, Moraga carried official requests, orders and threats warning

the Russians to withdraw from Spanish territory. At the same time

however, Moraga and the Russian commander made additional arrangements

for what became an illegal, yet thriving, trade between the subjects

of Spain and Russia, with the unofficial blessing of Governor

Arrillaga. Consequently, the governor did not discourage the activity,

which he regarded as a profitable channel for obtaining much needed

supplies for his province. At least three Russian shiploads of

goods were exchanged for foodstuffs at San Francisco during 1815.

Both the interim governor, Jose Arguello, and the new one, Pablo

Vicente de Sola, made feeble gestures in the direction of stopping

the contraband exchange. Neither of them carried out any serious

effort to enforce the orders of the Spanish government in this

respect.

Pablo Vincente de Sola,

a Basque from Villa of Nondragon, Viscaya, was born in 1761 into

the Hidalgo class. From November 11, 1805 to February 20, 1807

this bachelor served as ad interim habilitado general of the Californias.

On December 31, 1814 his appointment as Governor of Nueva California

was made, although he did not reach Monterey to take charge until

August 30, 1815. He remained in this office until late November

1822 when he set sail for Mexico. After that few details are known

about this last Spanish governor of the province.

In 1815, the old chapel,

which had been badly damaged by the 1812 earthquake, was torn

down to the foundations. Work started on a provisional chapel

until a new chapel could be completed in 1817. New roofs of tile

finally replaced the old ones of tule, which so frequently had

been destroyed by wind and rain. More significantly the Castillo

was rebuilt into a completely new structure, based on a horseshoe

design, in response to the Russian presence at Fort Ross.

In 1816, the American ship

Prisionera visited California and traded tools for needed

supplies.

On October 2, 1816, the

Russian brig Rurik arrived and anchored in front of the Presidio.

The world voyage, under the command of Lieutenant Otto von Katzebue

of the Russian Imperial Navy, came as a scientific expedition

but the visit to San Francisco no doubt also served as an opportunity

to check on the power of the Spanish government in California.

Fortunately for posterity

the Russians came to observe more than just the state of defense.

They brought with them Dr. Ivan Eschscholtz, surgeon, Adelbert

von Chamisso and Martin Wormskhold, naturalists and Louis Choris,

artist.

Eschscholtz provided some

of the first scientific information about the flora of present-day

California. They identified and named species during the course

of their work including Eschsholtzia Californica, the "Golden

Poppy" which was to become the state flower.

The artist Choris provided

the second rendering of the Presidio since the Renzanov visit.

The Spaniards and the Russians

hoisted their respective flags and exchanged cannon salutes. After

the ship anchored in front of the Presidio, the officers went

ashore to meet Luis Arguello, Comandante. The Spanish commander

sent some fruits and vegetables on board the ship for the crew

and dispatched a courier to Monterey with the news of the visitors'

arrival.

By October 4th the Russians

had set up a camp on the shore in sight of the Presidio, which

Kotzebue said still appeared as it had in Vancouver's descriptions.

Vancouver's earlier reports had been circulated around Europe

and were the reason for this and many subsequent visits to California

by many of the European powers of the time.

Governor Sola requested

of Lieutenant Kotzebue that Fort Ross be abandoned but the Russian

refused. On October 28 flag-hoisting and artillery fire provided

Rurik with an exciting departure from San Francisco after nearly

a one-month stay. The visit of Rurik marked the end of opposition

to foreign trade by Governor Sola. A critical need for supplies

outweighed strict royal orders.

Many ships visited California

in the five waning years of the Spanish government. One of these

was the French merchant vessel Le Bordelais under the command

of Lieutenant Camille de Roquefeuil of the French Navy in 1817.

This vessel was sent on a voyage around the world between 1816

and 1819 by its government.

In 1818 Lieutenant Ignacio

Martinez became the new comandante replacing Lieutenant Gabriel

Moraga who was posted to Santa Barbara. A native of Mexico City,

Martinez had entered the Santa Barbara Company some 25 years earlier

as a cadet. He did not welcome the new assignment at first because

he had to relocate with his four daughters but he and his wife

had five more children, did so and remained in the Bay area for

the rest of their lives. Martinez would hold many positions after

leaving the military, including appointments at San Rafael and

elsewhere. He died around 1850 at his ranch in Contra Costa County

where the county seat was named in his honor.

On November 20, 1818 Hippolyte

de Bouchard appeared before Monterey in the Argentina and Santa

Rose de Chacabuco and proceeded to sack the Presidio. The San

Francisco Presidio was asked to send reinforcements. However when

they arrived they drilled but did not engage the enemy. As pointed

out by Vancouver, the Spanish defenses could not withstand a determined

attack from a European force. The government sent reinforcements

from San Blas in the summer of 1819. San Francisco received 40

foot soldiers from the San Blas Infantry. In 1820, 20 artillerymen

came from Mexico under sub-lieutenant Jose Ramirez. Their arrival

represented the last important reinforcements to be sent from

Mexico.

Two years later in April

1822, the Mexican Empire was formed under Agustin Iturbide. Don

Luis Arguello, Comandante of the San Francisco District, remained

in command. However in November 1822 Arguello became the acting

governor of Alta California. A year later Agustin Fernandez San

Vicente came from Mexico to replace him. Arguello returned to

his position as comandante. With the fall of Iturbide from power

in March 1823, San Vincente left California for Mexico. In January

1825 Arguello decreed that presidial company strength should stand

at 70 to 75 soldiers, a considerable increase over previous official

levels. The funds to carry out such well-meaning plans were nonexistent.

To add further insult, pay continually fell in arrears. The Mexican

government responded by issuing a cargo of paper cigars in lieu

of cash.

On February 6, 1824 Arguello

reported to the minister of war in Mexico City that he would be

obliged to muster out the entire San Blas and Mazatlan Companies

as well as provisionally retire several presidial soldiers if

money were not immediately forthcoming. Increasing numbers of

men left the service voluntarily to take up what they hoped would

be more lucrative employment on ranchos or at the Pueblo San Jose.

Without loyalty and payroll benefits little remained to hold a

soldier in the service of the Mexican Republic.

Otto von Kotzebue returned

to San Francisco in 1824 and reported that little had changed

since his last visit in 1816.

A second Russian ship, the

frigate Cruiser, also visited in 1824. One of its officers, Dimitry

Irinarkhovich Zavalishin commented as follows: "But as danger

of attack from savages diminished or, at least, became to affect

only the more remote missions, they (the Spanish) began to permit

outside buildings at the presidios, and as a result it became

necessary to make passageways through the heretofore blank outer

wall. Lately, even Russian expeditions have had bakeries attached

to the outer wall for the baking of both fresh bread and rusks

for cruise. This is how San Francisco's presidio became a rather

formless pile of half-ruined dwellings, sheds, storehouses, and

other structures. The floors, of course, were everywhere of stone

or dirt, and not only stoves but also fireplaces were lacking

in the living quarters. Whatever had to be boiled or fried was

prepared in the open air, mostly on cast brick; they warmed themselves

against the cold air over hot coals in pots or braziers. There

was not glass in the windows. Some people had only grating in

their windows. The entrance doors to some compartments were so

large that one passed from the interior courtyard to the outside

through the wall on horse-back."

These comments point to

a practice begun during the Spanish regime, commanders received

permission to grant building lots to soldiers and other residents

within the range of 4 square leagues, 2 leagues in each direction

from the center of the presidio square. In 1825 American captain

Benjamin Morrell indicated that 120 households lived in the district

with approximately 500 gente de razon. Morrell also referred to

the walls around the Presidio that stood 10 feet high made of

freestone and surrounding the compound, the houses (in the Presidio)

and church. Several frame structures were recorded which may have

been built by the Russians.

The Royal Navy officer Captain

Frederick William Beechey anchored his ship, H.M.S.Blossom

at San Francisco on November 6, 1826. He immediately presented

his papers to Comandante Don Ignacio Martinez. Beechey departed

on December 28th but returned briefly in 1827. His comments were

similar to others from Europe, in that he found an unimpressive

group of buildings and low morale among the soldados.

The Mexican government had not missed the disarray and discontent, so obvious to Beechey and other visitors but the measures they were willing to take to improve defenses in their California outposts amounted to little more than rhetorical proclamations. The arrival of a new governor, Jose Maria Encheandia, and some reinforcements in the form of a 40-man infantry unit known as the Fijo del Hidalgo, bound for Monterey, caused ill will rather than increasing a sense of martial preparedness among the Californios who increasingly sawthemselves as a people apart from the Central Republic. This basic discontent led to the grass-roots revolt of the soldados at Monterey led by the dissident, Joaquin Solis from Mexico. They demanded not only back pay and back rations but also the removal of both the governor and the new comandante general. The revolt moved to San Francisco on November 5th, where Martinez was dismissed from his post as comandante. The rebellion came to an end in 1830. Sixteen of the major conspirators were sentenced to deportation. Governor Echeandia was replaced by Colonel Manuel Victoria. Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was appointed comandante of the San Francisco Presidio.

Vallejo joined the Mexican

military on January 8, 1824 as a cadet at Monterey serving with

the presidial company there for three years. He became a corporal

in 1825, rather than advancing directly to ensign as had been

the practice during the Spanish regime. The next year he went

on to become a sergeant, proving "an apt student, who learned

quickly, and had a great liking for discipline, authority, and

activities of military life." On July 30, 1827 just a week

before his 19th birthday, this aptitude and interest brought the

young Vallejo an ensignship when a vacancy came open at San Francisco

with the transfer of Santiago Arguello to San Diego. He would

remain at Monterey until April 1830 when he joined the garrison

in the Bay Area. Thereafter his career continued to move upward.

At age 29 he earned a captaincy and by 1836 held a commission

as a colonel. The man became a prominent figure in northern California

history and enjoyed a long life.

Again a new governor was

appointed. Jose Figueroa arrived in California in January of 1833.

He was instructed to restore confidence in the Mexican Government,

watch the Russians and American activities along the coast, and

to move toward the secularization of the missions. The latter

required the division of mission lands into self-supporting ranchos

and the replacement of the Franciscan missionaries by regular

parish priests. Seventy-five officers and men were assign to help

carry out these directives.

In April 1833, Governor

Figueroa ordered Vallejo to survey the areas north of the bay

with an eye to the establishment of another outpost. Vallejo was

given the title of Military Commander and Director of Colonization

of the Northern Frontier. These titles were contained in a letter,

which Vallejo kept secret, as requested, until 1847 when he revealed

them to the American Occupation forces under General Kearny and

caused them to be published in several newspapers probably to

strengthen the legality of titles to lands he had granted. The

letter set forth that the principal object of the northern expansion

is to arrest the progress of the Russian settlements of Bodega

and Ross. Two days later, Governor Figueroa authorized the establishment

of a pueblo in the valley of Sonoma entrusting full responsibility

for the new enterprise to the young lieutenant not yet turned

twenty-eight. Along with this authority came the effort to build

a barracks for the Mexican troops stationed there.

In 1834, Vallejo moved part

of San Francisco's garrison to Sonoma after severe storm damage

dictated another rebuilding, which never occurred because of lack

of funds. Rains caused deterioration at the Presidio and near

destruction of much of the Castillo. Toward the end of the year,

Vallejo recommended that the unrepairable conditions made it desirable

to sell off what could be salvaged at the Presidio to private

individuals in order to obtain some back pay for the troops. The

Presidio's stock could be transferred to Sonoma to start a national

ranch there. The governor agreed to the relocation and the scheme

to sell portions of the Presidio so long as a part of the reservation

remained for a barracks to lodge troops.

In 1835, Vallejo had transported

not only the last of the San Francisco garrison but also his own

family, to the new northern outpost. Soon the Presidio declined

to a caretaker status. The movement to the north placed the Spanish

closer to the Russians, provided a healthier environment for the

troops and signaled a new approach to housing and organization,

that of using barracks outside of walls and horse soldiers to

provide the main defense along with infantry and field cannon,

instead of fixed garrison defenses. Modern European armies were

already organized in this fashion. Vallejo constructed two-story,

wide balconied adobe barracks, which faced Sonoma's central plaza

to house Mexican army troops. The construction took place in stages

but was completed in 1840. Vallejo's family residence was a part

of these buildings, which also included some of the vacated mission

buildings. Called "El Cuartel" the barracks housed a

maximum of 40 Mexican troopers. Vallejo kept the mission chapel

active. A prominent part of his "Casa Grande" was a

three-story tower, which he used to oversee rangelands and farms

through a telescope. Several drawings were made over the years

of these buildings.

In the years after 1835,

more than 100 military expeditions set out from Sonoma with the

object of subduing the Wappos, Cainameros, or Satisyomis Native

Americans who more than once rose up and attempted to throw off

Mexican domination of the country around Sonoma. Many of these

expeditions were led by Vallejo himself but others were led by

Vallejo's younger brother, Salvadore, or by Sem-Yeto, the tall

chief of the Suisunes Native Americans whose Christian name was

Francisco Solano, and who came to be one of Vallejo's closest

and most valuable allies.

Movement to the north also

coincided with the establishment of the Pueblo of Yerba Buena.

The new settlement was destined to become the City of San Francisco.

In 1834 the presidial-pueblo of Yerba Buena was set up with a

six-man district council and an alcalde. A San Blas infantryman,

Francisco de Haro, was the first to hold that position. The anchorage

also moved to Yerba Buena as did some of the population who began

to strip the main garrison and the Castillo as well of what little

useful building materials they could find. However Vallejo did

leave a detachment of six artillerymen under Juan Prado Mesa to

maintain a token presence at the Presidio when the main force

relocated to Sonoma.

A forecast of the interest

of the United States in the California territory occurred in August

1834. Then the charge d'affaires in Mexico City approached the

central government with an offer to buy the San Francisco Bay

Area for $5 million dollars. The Americans wanted the harbor to

serve as a base for American whalers in the Pacific. Mexican authorities

gave consideration to accepting the offer but British diplomats

finally convinced them to hold onto the territory.

Coastal fortifications,

originally built to protect the population, had meanwhile all

but disappeared. The artillery stood unused and uncared for although

Vallejo recommended that the Castillo be rebuilt. As it was in

San Francisco, only one artilleryman remained to man the last

six cannon since Vallejo had ordered the relocation of several

of the serviceable guns to Sonoma.

According to Bancroft's

History of California, Vol. IV, pgs, 197-198 and 701, by

1841 only 24 artillerymen remained in all of Alta California and

they had charge of 43 serviceable pieces and 17 useless guns along

the coast. Eleven years earlier the ordnance inventory consisted

of 54 cannon, three of 24 pounds, two of 12 pounds; 18 of 8 pounds;

19 of 6 pounds; 11 of 4 pounds and one of 3 pounds. Twenty-three

of the guns were brass and 31 iron according to Bancroft, History

of California, Vol. II, Pg. 673.

In the next few years as

English, French, Swedish and American expeditions and travelers

visited the San Francisco Presidio, all had about the same comments.

The French government's representative, Duflot de Mofras in his

book Travels on the Pacific Coast, Vol. I, Pgs 228-229,

comments as follows: "the fort has been so completely abandoned

that a ship could easily send its small boats over the shore below,

and without attracting attention from the Presidio, carry off

the cannon that could be rolled down the cliff. The Presidio of

San Francisco is falling into decay, is entirely dismantled, and

is inhabited by only a sub-lieutenant and 5 soldiers-rancheros

with their families. The Castillo consisted of a horseshoe-shaped

adobe battery with 16 embrasures for cannon. Only three obsolete

guns and two good bronze pieces of 16 caliber, cast in Manila

were in place, all on wooden gun carriages which date from 1812

and are partially decayed. In the center of the horseshoe, the

barracks, used originally to house the soldiers, have fallen into

ruins. No one lived there nor did a ditch or other protection

to the rear exist to keep the place from being overtaken from

the side should the battery be manned."

In 1843, a Swedish visitor

G.M. Waseurtz af Sandels, " the King's Orphan", made

two crude illustrations of the Presidio and the Castillo that

are the last known before the American conquest. They illustrated

the above comments by de Mofras, but show both to be occupied.

Russia withdrew from Fort

Ross in 1841. In 1842 Mexico sent a new Governor with a ragtag

army, Brigadier General Manuel Micheltorena. He lasted no longer

than the rest.

Mexico's inability to protect

California invited foreign seizure. In October 1842 Commodore

Thomas Ap Catesby Jones of the American Pacific Squadron landed

at Monterey Bay and claimed Alta California's capital for the

United States based on information that the United States was

at war with Mexico. There was no opposition to this action. While

this action was premature and the claim was surrendered in a few

hours, it was the forerunner of future actions.

On the diplomatic side, in 1842 the United States sent John Slidell to Mexico City in order to reopen the negotiations that had broken off in 1835 for the purchase of the Bay Area. This time he was offering $25 million for all of the California territory. Once again Mexico refused the offer.