The military history of Angel Island began in 1850, shortly after the Mexican War, when President Fillmore declared the island a military preserve. When California entered the Union, in 1848 San Francisco bay was virtually defenseless. El Castillo de San Joaquin, the little Spanish fort at the entrance to San Francisco Bay, was a ruin, the result of poor construction, rain, earthquakes, and neglect. It was the only defensive works, with the exception of a crude single-gun battery on Black Point (Fort Mason), erected by either the Spanish or the Mexican authorities during their tenures. San Francisco’s lack of defense was of concern to the American authorities, and an 1850 commission prepared a comprehensive plan for the defense of the bay. As a result of that plan, artillery batteries were installed on Alcatraz, and construction began on what would become Fort Point, on the site of the old Castillo de San Joaquin.

Angel Island was to be part of the “second

line” of defense in the original planning, but for years

the island continued to lead a pastoral existence, home only to

a number of squatters who eked out a living by fishing and farming.

In 1858 the Army Engineers sent two officers to the island to

conduct surveys, but when they finished their work disappeared

into the files, and no other action was taken. In 1861 the Civil

War gave impetus to the work on the defenses for the bay; Alcatraz

had become a major fortress that eventually would mount more than

100 guns, and Fort Point was strengthened with additional guns

and men, but Angel Island and the “second line” of defense

existed only on paper.

Public concern over the inadequacy of San Francisco Bay defenses

continued to mount, however. Finally, in 1863, orders to place

guns on the island came from Washington. On August 24th Captain

R. S. Williamson of the Army Engineers was sent to the island,

where he made another survey, and recommended that artillery batteries

be placed on the island at Points Stuart, Knox and Blunt. These

were to be temporary batteries, with wooden gun mounts and earthen

emplacements. The initial military purpose served by Angel Island

was as an artillery post, part of the defenses of San Francisco

Bay.

Captain Williamson’s report was endorsed by the Department of the Pacific. Construction of the new batteries began in September, 1863, under the supervision of Colonel Rene De Russey, United States Army Engineers. That same month the Department of the Pacific ordered Company B, Third Artillery, to go into camp on Angel Island. On September 21, fifty-six men of Company B, under the command of Second Lieutenant John L. Tiernon, left Fort Point, and arrived on Angel Island the same day.

One of the first acts of the acting company commander was to name the new post “Camp Reynolds,” in honor of Major-General John Reynolds, commander of First Corps, Army of the Potomac, who had been killed by a sniper at the Battle of Gettysburg the previous July. General Reynolds had been a popular and much admired officer, considered by some to be the best officer in the Army of the Potomac. Lieutenant Tiernon then looked for a site on which to build quarters. He selected a long sloping hill that ran down towards a cove on the west side of the island; it had the advantage of being between the new batteries at Point Knox and Point Stuart.

While Colonel De Russey and the engineers worked to construct the artillery batteries, with some assistance from the men of the Third Artillery, a civilian contractor, began work on the Camp Reynolds garrison buildings. Progress was slow; the evidence suggests that most of the command did not get into quarters before winter—they spent the winter in tents. Two officers’ quarters were completed in 1863, together with some service buildings, but the balance of the original Camp Reynolds buildings, including two sets of barracks for enlisted men, were not completed until 1864. In that same year, the post’s first hospital (there would be three over the years) was built some distance to the north, in a cove that had been known as Racoon Bay or Glenn Cove. After the erection of the hospital and the surgeon’s and steward’s quarters, the cove became known as Hospital Cove, and is known today as Ayala Cove.

While the post was being constructed the Army Engineers were at work on the artillery batteries. Roads to the batteries on Point Knox and Point Stuart were completed by June of 1864. Construction on the Point Stuart battery began in November, 1863, and the battery’s armament, a ten-inch Columbiad (howitzer) and three thirty-two pounders, was mounted by August of 1864. One month later Point Knox was ready for service, armed with seven thirty-two pounders, an eight-inch Rodman, and two ten-inch Rodmans. The emplacements were earthen, and the guns were mounted on wooden carriages coated with coal tar for protection against the elements.

The construction on the batteries on Point Stuart and Point Knox went forward on schedule, but the work on the battery at Point Blunt did not. The great difficulty in traversing the distance between Point Blunt and Camp Reynolds made it necessary to place the battery under the command of Alcatraz, and man the battery with men from that post, who could more easily reach the point by water. A barracks and officers quarters had to be erected for their use. Excavations for the emplacement were completed by April of 1864, but there was a delay, and heavy rains damaged the parapet. The work was delayed until March of 1865, when the barge carrying the guns to the battery swamped on the beach. The final disaster occurred in May of 1865; the parapet dropped five feet and slid forward; the battery was abandoned, and the guns were removed in 1866. The barracks and officers’ quarters on the point became a sub-post of Camp Reynolds.

In July of 1864 General Irvin McDowell, Commanding Officer of the Department of the Pacific, made an inspection tour of Angel Island. Accompanying the Army officers and dignitaries on the tour was a young reporter who later would become famous as “Mark Twain,” but at the time, proud of being a reporter, called himself “Clemens, of the Call.” Clemens said the fortifications on Angel Island “were fast growing into formidable proportions.” That same month the Commanding Officer of Camp Reynolds reported that thirteen guns were mounted and there were 7,400 pounds of powder, and 2,600 rounds of shot and shell on hand.

When the Civil War ended, and the defense of San Francisco Bay no longer a paramount need, Camp Reynolds became a Recruit Depot, responsible for handling recruits on their way to posts in the west. A second change occurred in 1871, when Peninsula Island was placed under the control of the commanding officer of Camp Reynolds. (It was pointed out that the name was ludicrous—it was either an island or a peninsula, it couldn’t be both.) This property was what we know today as Belvedere, and it was made a military reserve by presidential order in 1867, as it was considered important for the defense of the approaches to the Benicia Arsenal and the Mare Island Naval Yard. No military structures were erected on the new reserve; patrols from Angel Island serving to protect the property from trespassers. In 1885 a legal opinion voided the government’s rights to the military reserve, and the commander of Camp Reynolds once more controlled just one island, not two,

During the last part of the Nineteenth Century the men stationed at Camp Reynolds were involved in what has become loosely known as the “Indian Wars.” The Army of the time was not large, and small units were scattered across the western United States. Troops were sent up and down the coast by steamer, and at one time or another regiments with headquarters on the island had men posted from Sitka, Alaska, to the Mexican Border. The 12th Infantry, at one time officially “stationed” on Angel Island, actually had troops at eleven different posts in three states or territories. The Ninth Infantry, with Headquarters at Camp Reynolds in 1869, had Company D, regimental headquarters, and the regimental band on Angel Island. The balance of the regiment was stationed at nine other locations, seven of them in California and two in Nevada. Units came and went, and the population on the island varied from 100 to 700, as soldiers from Camp Reynolds fought and scouted, provided guards and escorts, and patrolled the western United States. In 1873 Companies E and G of the 12th Infantry were sent north to fight in the Modoc War, both companies suffering numerous casualties in the conflict. In addition to providing troops for western outposts, Camp Reynolds continued its functions as a Recruit Depot, receiving soldiers new to the Army.

During this period Camp Reynolds had a number of commanding officers who had distinguished themselves in the Civil War. Two of them, William R Shafter and Orlando Bolivar Willcox had been awarded Medals of Honor during the war, and others, including John C. Tidball, August Kautz, William Henry French and John Haskell King, had outstanding war records. All of these officers had been awarded the brevet rank of brigadier-general or higher.

One of the enduring myths about Angel Island is that the island served as an “Indian prison” during the Indian Wars. At the time the Army did consider using a “garrisoned island” as a place to house such prisoners, who had become “quite numerous” at interior posts, but the idea does not appear to have ever become policy. In 1869 there were two Indian prisoners on the island, who were furnished with tents, clothing and rations, and had the freedom of the island. The 1870 census lists sixteen Indians on the island, aged from 15 to 46. This appears to have been the largest number of Indians ever held on Angel Island, hardly enough to make it a prison camp. It appears that these Indians were not captured in battle. They were listed as “Indian convicts,” and seem to have been troublemakers and petty criminals from the reservations.

New buildings were added to the post over the years;

a new hospital was built in 1869, closer to the post proper, a

chapel in 1876, three more barracks, and additional officers’

quarters. The population was obviously overwhelmingly made up

of soldiers and officers, but there were always a number of women,

quite a few children, and a number of civilians. In 1880, for

instance, there were 19 Chinese shrimp fishermen on the island,

eight of them married. Twenty-four Army wives were on the island,

in addition to six female servants and a hospital matron. There

were seven male servants, two of them employed by the Commanding

Officer, Colonel Kautz, a veteran of the Civil War, who also employed

two of the female servants; in effect the colonel had one servant

for each member of his family. The civilians included the manager

of the Angel Island quarry, the post sutler (storekeeper), and

a dairyman, whose herd of cows kept the post supplied with milk,

butter and cream. The island always had one or more herds of cows,

and flocks of chickens; being somewhat removed from the mainland,

a certain amount of self-sufficiency was required.

New buildings were added to the post over the years;

a new hospital was built in 1869, closer to the post proper, a

chapel in 1876, three more barracks, and additional officers’

quarters. The population was obviously overwhelmingly made up

of soldiers and officers, but there were always a number of women,

quite a few children, and a number of civilians. In 1880, for

instance, there were 19 Chinese shrimp fishermen on the island,

eight of them married. Twenty-four Army wives were on the island,

in addition to six female servants and a hospital matron. There

were seven male servants, two of them employed by the Commanding

Officer, Colonel Kautz, a veteran of the Civil War, who also employed

two of the female servants; in effect the colonel had one servant

for each member of his family. The civilians included the manager

of the Angel Island quarry, the post sutler (storekeeper), and

a dairyman, whose herd of cows kept the post supplied with milk,

butter and cream. The island always had one or more herds of cows,

and flocks of chickens; being somewhat removed from the mainland,

a certain amount of self-sufficiency was required.

Army life in the last half of the Nineteenth Century was harsh, with rigid class distinctions. Pay was low, as was morale. Following the Civil War desertions were a “constant problem.” The 8th Cavalry, which had some of its men on Angel Island, had a desertion rate of almost 42% in 1871. The situation was so acute that at one point a reward was offered to anyone in San Francisco who assisted in the apprehension of a deserter. The 9th Infantry paid $1800 in such rewards in 1868, and recovered 105 of the 212 men who had deserted. As a corollary to desertions, there was a pervasive and serious drinking problem. Because of it the post sutler was forbidden to keep “any description of wine, bitters, cordials, fruits preserved in liquor, or liquor in any form.” The post hospital kept all compounds containing alcohol under lock and key. There was widespread smuggling of “vile compounds, mostly low-grade whiskey,” from the mainland to the island. It is revealing that the construction of the first road to circle the island was cited as being “especially necessary to patrol the island, to prevent the landing . . . of small boats for whisky and deserters.” At least one of the reasons for low morale and excessive drinking at Camp Reynolds was the monotony, which one observer called “deadly.” Isolated from the mainland, operating on an unvarying military schedule, life on the island had a stultifying regularity. A resident of Camp Reynolds said, “The most exciting event of the day is the arrival of the steamer.”

In 1891 a Quarantine Station was built in Hospital Cove, the site of the original Camp Reynolds hospital, and the Army was forced to share the island for the first time. The new station was operated by the Marine Hospital Service. It was not welcomed by the Army; Camp Reynolds had had the island to itself for twenty-eight years, and felt no need of a neighbor. The station was built over Army protests.

In what seemed to be a repetition of the 1860s, the defenses of San Francisco Bay again became a matter of public concern in the 1880s. The Civil War batteries were either deteriorated, or obsolete—there had been no appropriation for harbor defenses in some years—and public outcries eventually brought action from the government. New batteries (known as “Endicott Batteries,” after the board that proposed them) were proposed for San Francisco Bay. The first such battery for the bay was built at Fort Point.

The first activity on Angel Island, in this new effort to arm San Francisco Bay, was the construction of a “torpedo,” or mine casemate at Mortar Hill, on the south side of the island in 1891. This casemate served as a control point for mines placed beneath the surface of the bay. At the time it was one of four such mine control points in the defense system for the bay.

In April of 1898 work began on Angel Island’s first permanent Endicott Battery, Battery Drew, located just south of Camp Reynolds and armed with a single eight-inch rifle on a non-disappearing carriage. Construction on this new battery began just three weeks before the start of the Spanish-American War—the war gave impetus to the construction, just as the Civil War had for the original batteries. The second new battery was Battery Ledyard, which was erected on the site of the old Point Knox Civil War battery, and armed with two five-inch rapid-fire guns. The third, and last, battery in the series was Battery Wallace, built above and behind Ledyard, and armed with a single eight-inch rifle on a disappearing carriage.

The war with Spain did not at first affect Camp Reynolds, but as the war went on the activities at the post steadily increased. Following Admiral Dewey’s success in Manila Bay troops were needed in the Philippines to follow up the naval success, and thousands of men left San Francisco for Manila, many of them passing through Camp Reynolds. The activity increased when the war ended, for it was promptly followed by what became known as the Philippine Insurrection. This little-known conflict would involve some 100,000 American troops before it was over, and Camp Reynolds became an integral part of the troop movements to the Philippines. Not only was the post shipping men overseas, it was receiving men returning from the fighting. Among them were men with tropical diseases, and in 1899 a Detention Camp was erected on the east side of the island for their care. As hostilities wound down thousands of men began returning for discharges, and a Discharge Camp was erected in 1901, also on the east side of Angel Island, adjoining the Detention Camp. By 1907 some 126,000 men had been discharged at the camp.

In 1900 the Army changed the name of the post on Angel Island to Fort McDowell, after General Irvin McDowell, who had died in San Francisco in 1885. General McDowell had been commander of the Union armies at the First Battle of Bull Run, and later became commander of the Department of the Pacific. The reason for the name change is not known, but General McDowell, while not recognized as an able leader in the field, was a good administrator, and had been an immensely popular figure in San Francisco. Reynolds, after all, was from Pennsylvania. With the change, Camp Reynolds no longer officially existed, and the name was no longer used.

In 1910 Fort McDowell began a major building program on the east side of Angel Island, using military prisoners from the Army Prison on Alcatraz as labor. Among the permanent buildings constructed were officers quarters, a Main Mess Hall, a Post Hospital, guard house, post exchange, barracks for enlisted men and service buildings. The post headquarters moved to the new garrison, which became the East Garrison of Fort McDowell; the former Camp Reynolds became West Garrison. Just prior to the construction of East Garrison, the Immigration Service built an Immigration Station, “the Ellis Island of the west,” at China Cove on the east side of Angel Island, just north of East Garrison.

Fort McDowell was very active during World War I, serving as a Recruit Depot for men entering the Army. Men drafted in the western states were sent to Fort McDowell, and held for about two weeks, during which time they would be given physical examinations, issued uniforms, and given some rudimentary military training. At the same time enlisted men returning from Hawaii and the Philippines for discharge, furlough, retirement or reassignment were being processed at the post. About 4,000 men a month passed through Fort McDowell during this period. Overcrowding became the rule—temporary tent encampments were erected at Point Blunt and on the old Camp Reynolds parade ground in an effort to ease the crush. The war-driven overcrowding was such that the newly completed Post hospital at East Garrison did not serve as a hospital when completed, but became a temporary barracks instead.

Following World War I military activity declined, and Fort McDowell went through a series of changes in official designations, finally becoming the Overseas Discharge and Replacement Depot in 1922. The distinctive unit insignia for the San Francisco Overseas Discharge and Replacement Depot is shown at the right. In this capacity it handled men leaving for, and returning from overseas posts. In 1926 it was reported that Fort McDowell was handling more men than any other Army Post in the country. An average of 22,000 men were processed at Fort McDowell each year between 1926 and 1938. During that same period 106,000 men were discharged at the post. After World War II began in Europe in 1939 activity on the island began to slowly increase again.

Pearl Harbor and American entry into World War II in 1941 gave Fort McDowell the impetus for its period of greatest activity. During the war it served as part of the huge San Francisco Port of Embarkation. The fort became a staging center for “casuals’—unassigned enlisted men—being sent as replacements to the Pacific Theater of War. Fort McDowell processed and shipped some 300,000 men overseas during the war. The number of men being processed reached such a point that the Main Mess Hall, which could seat 1,410 men at a time, was forced to have three seatings for each meal. The mess hall served more than 12,000 meals a day. Despite the increase in volume, veterans remember the food as being excellent.

The Immigration Service left Angel Island in 1940, following a fire which destroyed the Immigration Station Administration Building, and the site reverted to the Army. Following the start of World War II a 1,600-man mess hall, barracks, a guard house, a post exchange, an infirmary and a recreational building were added to what had been the Angel Island Immigration Station, and the site became the North Garrison of Fort McDowell. Part of North Garrison functioned as a Prisoner of War Processing Center for Japanese and German prisoners of war. The POWs were processed there before being shipped to permanent prison camps in the interior of the country. The first prisoner of war captured by American forces in World War II, the commander of a Japanese midget submarine at Pearl Harbor, was processed at North Garrison.

When the war with Japan ended, in August of 1945, Fort McDowell was almost swamped by the number of servicemen returning from overseas duty in the Pacific Theater. As the troop transports brought soldiers home from the Pacific, they were processed at Fort McDowell, ferried across the bay to Oakland or San Francisco, loaded on trains and sent off to be discharged at their original induction centers. During this hectic activity twenty-two troop trains were loaded in one day; twenty in Oakland and two in San Francisco. It was thought to be a record of its kind. Activity began to wind down in 1946, and the Army decided to close Fort McDowell. The Army left Angel Island in August of 1946, and the island was classified as surplus property

Following the departure of the Army, a debate began as to what the future of Angel Island would be. Finally, in 1954, after a good deal of controversy, debate and travail, 36 acres of Ayala Cove, on the north end of the island became a California State Park. However, that same year the Army returned to Angel Island to build a Nike Anti-aircraft missile site at Point Blunt, on the south end of the island. This site—manned by Battery D of the 9th Army Antiaircraft Artillery Regiment—was one of eleven such sites built in the San Francisco Bay area during the Cold War. The Angel Island battery had three launching sections, each with four missile launchers, and was armed with liquid-fueled Nike-Ajax missiles. An Integrated Fire Site, with three radars, two control vans, and a ready room was constructed on Mount Ida, the highest point on the island. About one hundred men manned the missile battery; they were quartered in what had been the Fort McDowell Post Hospital. The missiles were obsolete by 1962, and the anti-aircraft battery left the island that year.

Additional acreage had been added to Angel Island State Park in 1958, and the entire island was declared a California State Park in 1963. Today the entire island is open to the public, with regular ferry service from San Francisco and Marin. Many of the historic buildings at Camp Reynolds and Fort McDowell are still standing, and at Camp Reynolds a restored officer’s quarters is open to the public. The Spanish-American War battery sites still exist, although the guns have been removed.

Most facilities on the island are available April-October. If you plan a visit, contact the Tiburon ferry at angelislandferry.com or at 415-435-2131. The San Francisco ferry can be reached at 415-773-1188. There are picnic facilities, and visitor centers at Ayala Cove, the Immigration Station, and East Garrison. There is a deli, and bicycle and kayak rentals. There are nine environmental camp sites available on the island—for information on camping call the park ranger office at 415-435-5390.

The Angel Island Association provides docents during the season at Camp Reynolds (West Garrison), Fort McDowell (East Garrison) and the Immigration Station. Motorized tram tours of the island are available for visitors, and docent-led tours can be arranged through the Angel island Association. For complete information on Angel Island go to www.angelisland.org, or call the Angel Island Association at 415-435-3522.

After a century of public service, Angel Island is now open for public enjoyment.

| Date | Evert |

| 6 November 1850 | President Millard Fillmore issues an executive order declaring that Angel Island (as well as other areas in San Francisco) is a military reservation. This is largely ignored and the status quo is maintained for several years. |

| 20 April 1860 | President James Buchanan issues an executive order declaring that Angel Island is again a Federal military reservation. |

| 2 April 1863 | The War Department begins construction of fortifications on Angel Island |

| 12 September 1863 | Camp Reynolds is established. |

| 1 November 1863 | Construction of fortifications at Point Stuart and Point Blunt begins. |

| 7 November 1863 | Orders to construct barracks at Camp Reynolds received. |

| 25 July 1864 | Batteries at Point Stuart and Point Knox completed |

| 20 September 1864 | Battery at Point Blunt completed. Quarters for 120 enlisted and three officers as well as wharf were built at the point. Although on Angel Island, this battery was under the operational control of Ft. Alcatraz. |

| October 1864 | A road from the main garrison of Camp Reynolds to the hospital at Raccoon Cove (now Ayala Cove) is built. |

| 1864-1869 | Without the approval of the Corps of Engineers, Brevet Major George P. Andrews built and maintained a five-gun water battery at the head of Camp Reynolds' wharf. Work was continued on this fortification through at least 1869. Later howitzers were added to the rear of the battery near the post's flagpole. |

| 6 June 1865 | The battery at Point Blunt was declared unserviceable due to settling of the parapet. By 1869, three of the guns slid into the bay and the battery was abandoned. Barracks and officers' quarters come under the control of Camp Reynolds |

| April-October 1866 | Camp Reynolds temporarily abandoned. |

| 26 October 1866 | Camp Reynolds designated as the Depot for the receiving and distribution of recruits. |

| 30 June 1869 | Camp Reynolds becomes the headquarters for 12th Infantry Regiment. |

| 9 May 1885 | The Point Knox Fog Signal Station is authorized. |

| 16 January 1886 | The Endicott Board recommends improvement of harbor defenses at San Francisco in general and Angel Island specifically. |

| 22 Dec 1888 | Permit issued to US Marine Hospital Service for a National Quarantine Station in accordance with 25 Stat. 356. |

| 24 April 1889 | The Secretary of War formally releases 10.16 acres of land at Hospital Cove to the Treasury Department. |

| 4 March 1890 | Construction begins on the Quarantine Station. |

| 28 January 1891 | The Quarantine Station turned over to the US Marine Health Service. |

| 30 August 1893 | An additional 12 acres was transferred from the War Department to the Treasury Department for the Quarantine Station. |

| 19 March 1897 | Section I of California Act of 19 March 1897 cedes tideland adjacent and contiguous to island to the Federal reservation. |

| 1 April 1898 | Construction of Battery Drew, the first of the Endicott Board fortifications, begins. |

| June 1899 | Major General William R. Shafter, commander of the Department of California, established a Detention Camp at Camp Summer on Quarry Point. |

| October 1899 | Work begins on Battery Wallace. |

| 27 January 1900 | Work begins on Battery Ledyard. |

| 4 April 1900 | In accordance with War Department General Orders 43, the post is renamed Ft. McDowell. |

| 1 May 1900 | Battery Drew becomes operational. |

| 16 October 1900 | Telephone at telegraph service installed at Camp Summer Detention Camp. |

| 1 November 1901 | Discharge Camp opens at Camp Summer on Quarry Point. |

| 19 September 1903 | The "Depot of Recruits and Casuals" is moved from the Presidio of San Francisco to Angel Island. |

| 8 July 1905 | The Secretary of War approves the transfer of ±10 acres to the Department of Commerce and Labor for Immigration Station. |

| 30 September 1905 | The Quartermaster General of the US Army includes Ft. McDowell in a recommendation of posts to be abandoned or rebuilt. |

| October 1908 | Immigration Station completed. However, no funds for operations are available at the station. |

| 6 April 1909 | An additional 4.2 acres is transferred from the War Department to the Department of Commerce and Labor for the Immigration Station. |

| 4 June 1909 | General Recruit Depot established. The 8th Recruit Company arrives on 6 June 1909. Two additional companies follow later in the summer. |

| Summer 1909 | Construction begins on a larger permanent garrison at Quarry Point to house the General Recruit Depot. This area becomes what is known by 1925 as the East Garrison. |

| 21 January 1910 | Immigration Station officially opened. |

| 24 February 1914 | Survey recorded with the County Recorder of Marin County. Reference Records of Survey No. 24. |

| 23 October 1914 | Permit issued to Lighthouse Service, Department of Commerce and Labor for light and fog signals at Points Blunt and Stuart. |

| August 1919 | Recruit Depot renamed "Recruit and Replacement Depot." |

| November 1922 | Recruit and Replacement Depot renamed Overseas Discharge and Replacement Depot. |

| 1922 |

|

| 23 August 1925 | Water condensers installed at Immigration Station. Barging of water discontinued. |

| 30 November 1925 | The first official use of the terms, "East Garrison" and "West Garrison" is noted. |

| 1933 | Post incinerator constructed at East Garrison. |

| 1935 | The last case of a quarantine detention occurred when a Japanese family of three was detained when it was thought they had small-pox. |

| 30 September 1937 | The Immigration and Naturalization Bureau announced that new facilities would be built in San Francisco. |

| 2 April 1938 | Extensive program of buildings and grounds begins at East Garrison. |

| 1 July 1939 | Lighthouse Service transferred to and later absorbed by US Coast Guard, Department of the Treasury. |

| 9 July 1940 | Contract was let for new Immigration Station in San Francisco. |

| 4 February 1941 | Immigration Station property returned to the War Department and becomes the Ft. McDowell's North Garrison. |

| 8 December 1941 | Prisoner of War (POW) Processing Station established at North Garrison. Ft. McDowell comes under operational control of the San Francisco Port of Embarkation (SFPE) headquartered at Ft. Mason. |

| 1942 | Coast Artillery returns to Ft. McDowell. The 216th Coast Artillery Regiment places four 90mm antiaircraft guns on the island. Three are placed at the three Endicott period fortifications and one is located at an undisclosed location on the western side of the island. |

| 25 May 1942 | Camp Stoneman begins to receive troops and rapidly begins to assume Ft. McDowell's duties. |

| 16 June 1942 | The status "Overseas Discharge and Replacement Depot" is officially removed from Ft. McDowell. |

| 23 February 1943 | The first rotation of soldiers (89 officers and 1,608 enlisted) arrives at Ft. McDowell from Hawaii. |

| 12 July 1946 | Ft. McDowell is declared surplus by the Army. Quarantine Station and Fog and Light Stations were continued by the parent agencies under existing permits and agreements. |

| 20 September 1946 | Ft. McDowell is turned over to the District Engineer. |

| 12 February 1947 | All buried remains still in the post cemetery are removed and re-interred in the Golden Gate National Cemetery. |

| 10 June 1947 | Custody of Ft. McDowell is transferred to the War Assets Administration (WAA). |

| 11 October 1948 | Marin County applies for the island for historical park development. |

| 26 June 1950 | The Secretary of the Interior reserves Angel Island for disposal to the State of California or its political subdivision. With the exception of the 34.13 acres at Hospital Cove under control of the Public Heath Service and a total of 7.7 acres used by the Coast Guard, all land is transferred to the Bureau of Land Management. Sometime during 1950, the Quarantine Station is moved to San Francisco. In keeping with the original permit, the land is returned to the Department of the Army (formerly the War Department). |

| December 1950 | Three buildings are permitted to the Department of the Navy for use as a degaussing station. |

| 4 May 1951 | The State Parks Commission agrees to purchase the island at the 1947 WAA discounted price of $194,595 if a local park authority would assume management and protection under a lease. |

| 26 January 1953 | The San Francisco County Board of Supervisors approved a resolution to place the island on its park and recreation master plan. |

| 5 February 1954 | The Secretary of the Interior grants a permit to the Department of the Army to operate an anti-aircraft missile site. |

| 15 April 1954 | With the exception of 36.82 acres at Hospital Cove under control of California State Park Commission, three light stations under the Coast Guard, and the small degaussing station at the North Garrison which is under control of the Navy, the entire island is once again under Army control. |

| 30 April 1954 | The California Division of Beaches and Parks occupied the Hospital Cove property under the historical park classification. |

| 24 August 1954 | Contracts for the construction of the Nike-Ajax missile facilities are signed. |

| 26 August 1954 | Construction of the Nike-Ajax facilities began. |

| 1 March 1955 | The State of California receives title to 35 acres at Hospital Cove. |

| 20 April 1955 | The Nike-Ajax missile site is accepted by the Army and dedicated on 9 May 1955. The site is manned by Battery D, 9th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion, which became Battery B, 2nd Missile Battalion 51st Artillery. Officers and men, including 18 dependent families, are housed in the East Garrison area of the former Ft. McDowell. |

| 10 December 1958 | The State of California receives title to an additional 183.83 acres of land behind Hospital Cove, including Mount Livermore. This grant is subject only to existing permits to the Army which continues to operate the IFC radar from the top of Mount Livermore. |

| 1962 | Navy closes its Degaussing Station. Army deactivates Nike-Ajax missile site. |

| 27 December 1962 | Control of the remaining 517.24 acres passes to the State of California. |

| 29 July 1963 | The State of California receives title to the remainder of Angel Island, less the Coast Guard Light Stations at Points Blunt and Stuart. |

| 25 September 1963 | Demolition work on 110 old and dilapidated buildings approved. |

| 27 October 1972 | Under the provisions of Public Law (PL) 92-589 Sections 1 (86 Stat 1299), which established the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, control of the property that hosts the active USCG light stations transfers to the National Park Service. |

| July 1976 | State Legislature appropriates $250,000 to restore and preserve Immigration Station Barracks as a state monument. |

| 1977 | The National Park Service granted a Special-Use Permit to the Coast Guard for continued access, operation, and maintenance rights to the existing navigational aids as provided in section 3.(g) of P.L. 92-589. |

| 1983 | The Immigration Station is opened as a museum. |

| 2013 | The California Volunteers Living History Association opens the East Garrison Guardhouse as a military museum focusing on the island's military history. |

| Present | Angel Island is currently owned by the State of California and operated as a State Park. The two former Coast Guard Stations are currently owned and managed by the National Park Service |

|

|

|

|

|

World War I |

|

| US Army Order of Battle 1919-1940 | 1919-1941 |

|

| 7 December 1941 |

|

|

| Army of the United States Station List | 1 June 1943 |

|

| Army of the United States Station List | 7 April 1945 |

|

| 9th Sevice Command Station List | 7 April 1945 |

|

| Army of the United States Station List | 7 April 1946 |

|

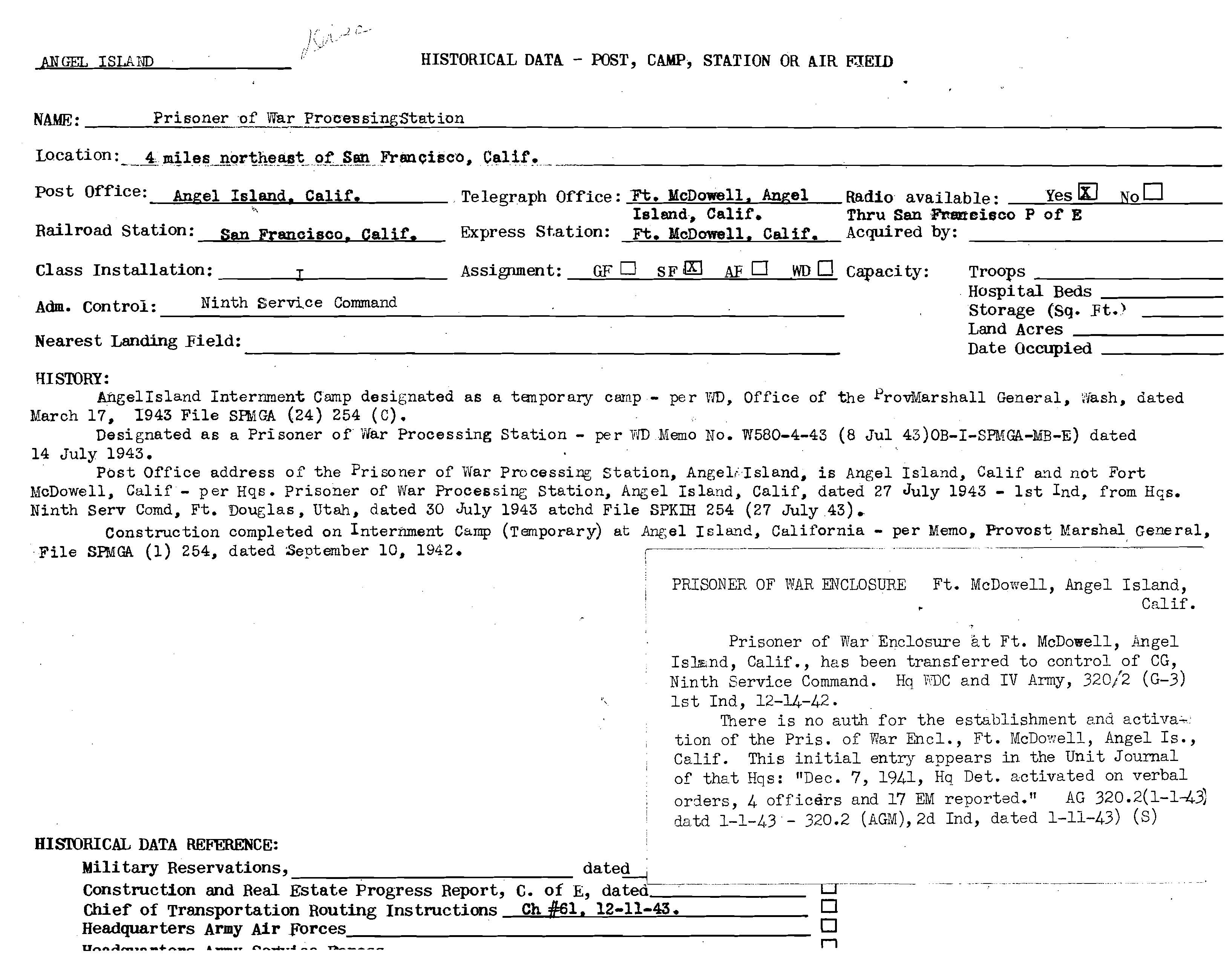

View of Camp Reynolds about 1890. Enlisted mens barracks at left center, with Officers Row at a further distance. Steeple of Post Chapel can be seen on far hillside. A number of these buildings are still standing Barracks, built in 1864, were considered by surgeon, "Well ventilated, and well warmed by large stoves, but imperfectly lighted. They are not lathed or plastered nor ceiled, a very great mistake in this windy climate, and detrimental to the health of the men." Barracks row is along foreground of picture, officers row parallel to walk in center; chapel, later schoolhouse, is on hill to right center. cemetery is in fenced enclosure behind officers' row and to right of flagpole; in 1879 it contained 32 graves. When 1866 inspection took place, post had three officers, 60 men, and 28 guns. Inspector said he found post in "Remarkably good order. There was nothing in the management of it to which exception could be taken."

| BAK | Bakery | LAUN | Laundry |

| BAND Q | Band Quarters | MH | Mess Hall |

| BLK | Blacksmith | ORD | Orderly Room |

| CH | Chapel | OQ | Officer Quarters |

| COMM SGT Q | Commisary Sergeant's Quarters | POST TR | Post Trader |

| GH | Guard House | QM ST | Quartermaster's Stores |

| H | Hospital | SCH | School |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5:30 AM – Lights on

The Western Electric SAM-A-7/M1/MIM-3 Nike Ajax

The Nike Ajax was the world's first operational surface-to-air guided missile system. Its origins lay in the immediate post-war time, when the U.S. Army realized that guided missiles were the only way to provide air-defense against future fast high-flying bombers. Western Electric became the prime contractor for the XSAM-G-7 Nike missile system and Douglas as the primary subcontractor was responsible for the missile airframe.

The first unguided Nike missiles were fired in 1946, but problems with the original multi-rocket booster (eight solid-fuel rockets wrapped around the missile tail) soon led to delays in the program. In 1948, it was decided to replace this booster pack with a single rocket booster, attached to the back of the missile. The main propulsion of the missile was a Bell liquid-fueled rocket motor, and the flight path was controlled by the four small fins around the nose. In November 1951, the first successful interception of a QB-17 target drone succeeded. The first production Nike (which had been redesignated SAM-A-7 in 1951) flew in 1952, and the first operational Nike site was activated in 1954. By this time, the missile had been designated by the Army as Guided Missile, Anti-Aircraft M1. The name had changed to Nike I, to distinguish it from the Nike-B (later MIM-14 Nike Hercules) and Nike II (later LIM-49 Nike Zeus). On 15 November 1956, the name was finally changed to Nike Ajax.

The Nike Ajax missile used a command guidance system. An acquisition radar called LOPAR (Low-Power Acquisition Radar) picked up potential targets at long range, and the information on hostile targets was then transferred to the Target Tracking Radar (TTR). An adjacent Missile Tracking Radar (MTR) tracked the flight path of the Nike Ajax missile. Using tracking data of the TTR and MTR, a computer calculated the interception trajectory, and sent appropriate course correction commands to the missile. The three high-explosive fragmentation warheads of the missile (in nose, center, and aft section) were detonated by ground command, when the paths of target and missile met.

One of the major disadvantages of the Nike Ajax system was that the guidance system could handle only one target at a time. Additionally, there was originally no data link between different Nike Ajax sites, which could lead to several sites engaging the same target. The latter problem was eventually solved by the introduction of the Martin AN/FSG-1 Missile Master command-and-control system, with automatic data communication and processing. Other problematic features of the Nike Ajax system were the liquid-fuel rocket motor with its highly toxic propellants, and the large size of a complete site with all components, which made Nike Ajax to all intents and purposes a fixed-site air defense system.

By 1958, nearly 200 Nike Ajax sites had been activated in the United States. However, the far more advanced MIM-14 Nike Hercules soon replaced the Nike Ajax, and by late 1963, the last Nike Ajax on U.S. soil had been retired. In 1963, the Nike Ajax had received the new designation MIM-3A. Despite the use of an MIM (Mobile Intercept Missile) designator, the mobility of the Nike Ajax system was more theoretical than actually feasible in a combat situation.

The MIM-3A continued to serve with U.S. overseas and friendly forces for many more years. In total, more than 16,000 missiles were built.