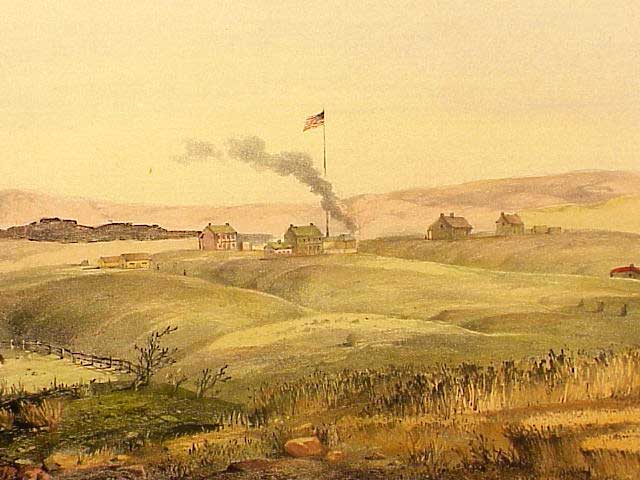

When the Army Inspector visited it in 1854, the place was five years old. He found that there was Benicia Barracks, which was headquarters for the 3rd Artillery, "in a good state of discipline . . . well quartered, a good hospital and bakery . . . and all public property in a good state of preservation."

The contractor continued the projects, including a 100- by 40-foot stone storehouse, in order to finish before the rainy season. He figured he would take his chances on being paid.

A third element of Benicia was the Benicia Subsistence Depot. headed by an Artillery officer and charged with providing food for the West. The problem: by the time it got by sea around the Horn or across Panama. there was more that needed condemning than could be kept. The recommendation was, buy foodstuffs locally where "they can be obtained to any desirable extent and where they can no doubt he had at less price."

The tour of Benicia was not over . . . Benicia Quartermaster's Depot was under the charge of a Quartermaster Captain and had on its rolls a diverse variety of items. The good captain was "commodore" over a fleet of one sailing brig and a schooner, both used in moving supplies between San Diego and Puget Sound, and a sloop, used in moving supplies between Stockton. He employed 26 civilians, including a ship captain at $5 a day, and spent just under $100,000 a year in supplying the Pacific Army.

It had a role in the Camel Experiment, too, although a final one. Many of the humped creatures who were veterans of the Beale expedition were herded from Fort Tejon and Camp Drum, near Los Angeles, to Benicia in 1863. Here they were sold at auction on February 26, 1864. Today, these barns are the Camel Barn Museum

It was a major recruit camp for California Volunteers and was enlarged with new barracks just in time to beat the snows and heavy rains of California's 1861-62 winter. This same winter brought misery to the many less fortunate camps that shivered under tents elsewhere in the state.

Battles as such never were fought from here, but the Civil War was close. Sentries fired at a ship that violated the 200-yard boundary line. Sentries watched in expectation when two other ships collided near the wharf, not accidentally but apparently in good commercial rivalry.

And the troops gathered in July 1863, to witness a tragic ceremony, the firing squad execution of private found guilty of murder and desertion. Formed in three sides, the soldiers watched while the prisoner was blindfolded and seated on his coffin. He fell backward into it as 11 bullets found their mark; one of the 12 muskets had a blank cartridge so that each man could feel he did not fire a fatal shot.

When the war ended., Benicia still had a roll. Companies were sent out by sea to Southern California to cross the deserts and outpost the forts of Nevada and Arizona. To Benicia, the end of a war meant only a reduction in activity, not a cessation. So it had been in the 1890's. the World Wars (bombs dropped on Tokyo by Alameda native James Doolittle came from Benicia), and the Korean War. Unlike most other western forts, Benicia had a role play that remained long after the frontier had been settled